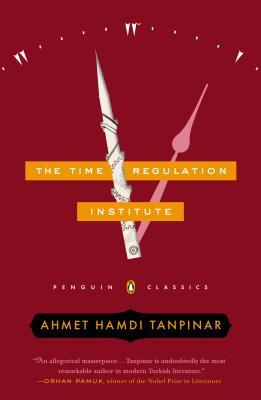

Tanpinar (1901-1962) is one of the deans of Turkish literature, according to Orhan Pamuk, he of the Nobel Prize for literature. The master narrative of Tanpinar’s novels is its identity. Is Turkey Asian and Islamic or European and secular if not Christian. Is Turkey a traditional society rooted to and limited to the past or modern society making and re-making itself.

These themes are embodied in the satire in the creation and evolution of the Time Regulation Institute, a private corporation which, for a fee, will adjust clocks and watches to the right time in kiosks around the country. As life becomes more regulated, the demand for this service grows. No longer do sunrise, high noon, or sunset mark the days but rather hours and minutes.

The corporation is paternalistic, nepotistic, sexist, incompetent, and succeeds despite itself. It becomes home to a psychoanalyst who wishes to study its members, an alchemist who wants to use the clockwork mechanism for some purpose or other but he is secretive about it, wives, nephews, cousins, European trained scientists who cannot get any other work in a society where suspicion of foreign taint is routine, concubines, and wastrels. Its counter staff are all attractive young men and women in smart uniforms and they rake in the dosh.

After four hundred pages all this is laboured. The novel unfolds as a memoir by Hayri Irdal, the Institute’s first employee. There is much background of the various, idiosyncratic, zany members of his family, and the brooding presence during his formative years of a large long case clock that seems to work when it wanted to and at no other time.

The Institute is so successful that it attracts the interest of the government in search of tax revenue, and other shysters in search of easy opportunities. In the wings we have a double murder and suicide involving Irdal’s relations and friends. None of it taken too seriously.

In a difficult press conference in the early days of the Institute a parable was used to explain its purpose. Ahmet the Timely from centuries ago was quoted and his sagacity struck a nerve in the public. There was a demand to learn more of this sage. Despite qualms, Irdal writes a biography of this completely fabricated character, which is a great success and does much to cement the place of the Institute, despite the quibbles of some pin headed dopes in universities who point out that this man never existed.

The satire is the superficiality of it all, which in fact leads to its success. The fact that Ahmet did not exit frees Irdal from sticking to boring facts. The fact that no one needs to have the time regulated makes it a perfect commodity.

Perhaps to a Turkish reader what is most conspicuous is what is not said. Not a word about women’s head scarfs in the many references to the uniforms. Not a word about the calls to prayers five times a day as regulators of life.

Ahmet Tanpinar

Ahmet Tanpinar

As with Russian novels, I continue to find it hard to distinguish the characters by name, the more so with women whose names are strings of letters. How parochial am I.

Skip to content