Guilty secret number 71.

I learned much about manhood from Randolph Scott. Who? Randolph Scott (1898-1987), the movie actor. His westerns in the 1950s left an indelible imprint on the prepubescent consciousness of any boy who saw them and was conscious. This second criterion eliminates quite a few. Scott was everyman, whereas John Wayne was always much bigger than life. It was fun to watch the Duke, but no normal boy could aspire that high. Scott was so much lower key, he might live around the corner going about his business.

He was taciturn, honourable, persistent, and polite. For years I have toyed with watching the famous (in a quiet way, befitting his screen persona) seven films he made at the end of his career with Burt Kennedy (the writer) and Budd Boetticher (the director) in the Sierra Nevada mountains. I may have seen them each once upon a time, but the hazy ambition was to watch them in sequence. However, lacking the courage of my convictions I never got around to ordering them on DVD, and the local Civic Video did not have them or access to them. In any event the DVD collection on the market is incomplete.

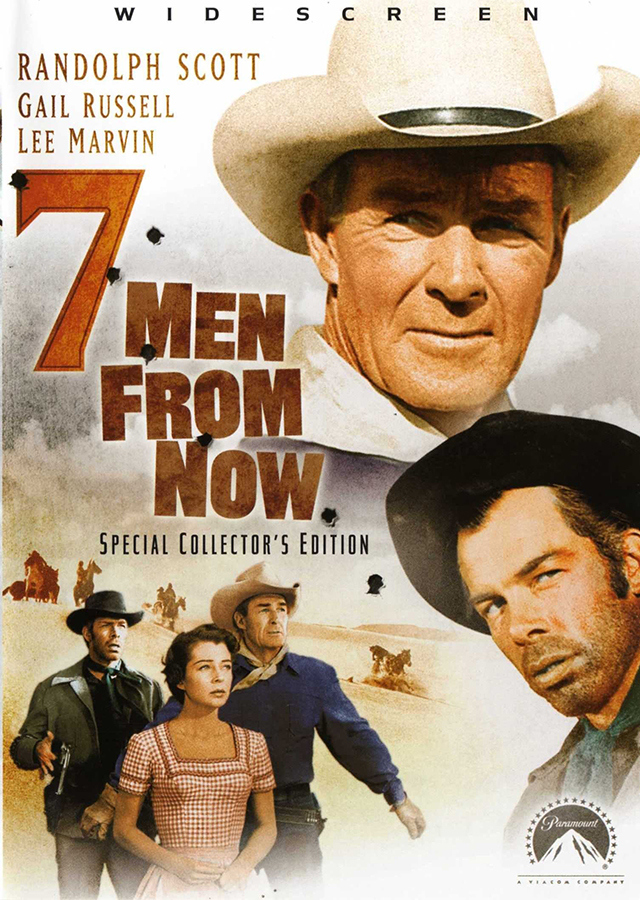

Then came the miracle of You Tube and there I discovered ‘Seven Men from Now’ (1957). The candle was lit, and the next night I dialled it up.

When it was released in 1956 Scott was almost sixty years old. That was the year of Wayne’s greatest film, ‘The Searchers.’ and while the two movies share the conventions of the western there are differences. Let me see if I can put my finger on some of the difference(s).

It starts it the middle at a time when linear story telling was the dominant approach. At the outset Ben Stride (Randolph Scott) seems ominous, and even malevolent. Though the narration soon reveals he is a man on a deadly mission to find and kill the seven men who robbed a Wells Fargo Office during the course of which they shot and killed a clerk, this being Stride’s wife. Thus we have a tale of revenge. Seven to one against Randolph Scott. Don’t take the bet!

He kills the first two within five minutes of run-time. That is fast action. It also seems unjustified. Is not the good guy supposed to try to arrest them and take them back to jail, not provoke a gun fight?

While Scott pursues the villains, in parallel that wonderful heavy Lee Marvin pursues the gold they stole. From the second scene onward, we all know that in the end it will come down to Randolph Scott versus Lee Marvin at even money. Marvin’s villain has a certain vulgar charm and a great deal of intelligence; he is not ravening beast that villains are sometimes made to be. He makes a superb foil for Scott’s reticent decency.

There are some nice twists and turns, personal growth, and irony that is unspoken but revealed in the actors’ faces, all too subtle for the Hollywood hammer these days. Truth to tell, there are also some gigantic plot holes that I will pass in silence. Plot holes remain a common Hollywood currency.

While there are rumours of restive Apaches, these indians are portrayed as victims. The real evil ones are the robbers, and Lee, as he shows soon enough. There is an obligatory old-timer who adds a lighter touch to one scene with some self-deprecating humour. I suppose since Gaby Hayes the old timers are there also to show that a man can grow old in the wild west. The conventions of the western are honoured in this.

There is some marvellous countryside as the wagon (loaded with the illicit gold) rolls to its destiny. It has pastoral moments.

Through it all Scott utters very few words, but when he does, we all know he means exactly what he says, and says exactly what he means — not one word more, not one word less. We all also know he will do what a man has to do in a quiet, dignified way. Wow! What a guy.

By the way, the female lead, Gail Russell, had near-clinical stage fright in front of the camera, and dealt with it by drinking whiskey. She had the reputation of being unreliable and the director Boetticher, the wiki-gossip goes, made a considerable effort to coax her through her scenes and to keep her off the drink during the production. It was her first film in four years and one of her last.

John Wayne made many westerns but he did a variety of other films, while Scott more or less settled in the western genre and stayed there. He accepted and made his own the type casting of the strong, silent loner. Apart from his early career, and the war years, his film credits are westerns, westerns, and westerns, including some based on stories by that stylist of the sage brush, Zane Grey.

By the way, the main difference between ‘Seven Men from Now’ and ‘The Searchers’ is John Ford with his capacity for poetry, faith in the camera to show the grandeur of nature and the small size of men, irony, and even sense of humour. ‘Seven Men from Now’ is just much lower key, nothing mythic about it.

Next up will be ‘The Tall T’ released in 1957.

Skip to content