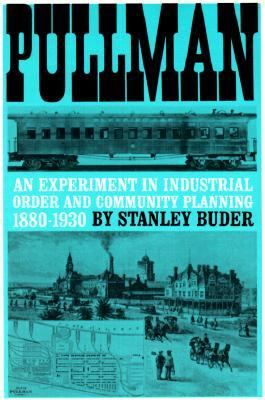

When doing homework for our trip to Chicago I came across reference to Pullman railway cars, a fascinating business model in itself. Those references also mentioned George Pullman’s artificial community, the eponymous Pullman. It was time to find out more.

Pullman made a fortune from the railway cars that bore his name from 1867-1968.

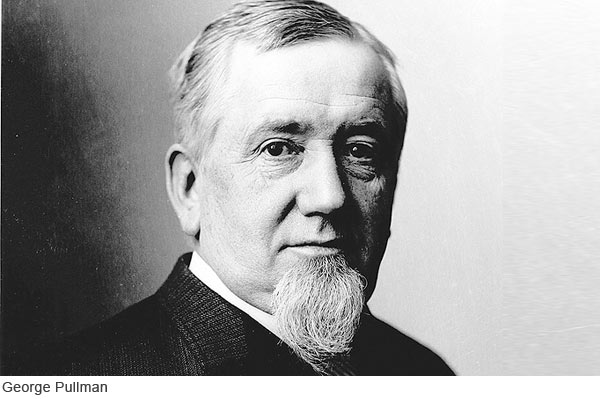

George Pullman.

George Pullman.

As railroads were rebuilt after the Civil War and extended coast-to-coast, Pullman built ever more of them and had to expand the manufacturing capacity. Because in his business model the staff of the cars was also contracted with the cars (of which he always retained ownership), he also had to recruit and train staff to maintain the Pullman standard. To do so, he bought more than 4,000 acres south of Chicago and set up a new factory and built a town around it.

To recruit first class mechanics (the term that applied to all skilled workers in his factory), to ease the commute of workers who lived in Chicago, and to satisfy his philanthropic self-image he built a community for his workers called Pullman, after the factory, not after him personally in the first instance. It would offer all the necessities and conveniences of town life from clean water, sanitation, paved streets, schools, libraries, theatres, and so on, all laid down in a plan and built before the first inhabitant moved in. There were would be no demon rum, no gambling, no prostitution and related vices.

The dwellings were varied in size and the occupants rented them from the Pullman Company at a rate calculated to return 6% on the investment of building and maintaining the community, that being the return the Pullman Company realised on its other investments. This return was important because Pullman wished to prove to other robber barons that such social investment was profitable. The author found that it never did quite make 6%, more like 4.5%, something that the Pullman Company kept secret.

Pullman employees had first priority for the housing, but some others also rented there though not many because there was nothing there but the Pullman factory in the early days. The homes were subject to occasional inspections to identify maintenance needs and to insure that the occupants were taking care of them. At first the rent was extracted from salaries before they were paid, but a court struck that down in a class action. Nonetheless when paid, Pullman employees could not leave the pay desk without paying the rent.

What’s so good about utopia? The town of Pullman offered peace and quiet, recreation for families (parks, theatres), libraries and schools, sanitation, clean water, fuel, and the like, all laid on. It was run by a business manager because it was unincorporated. Ergo the residents had no say whatever in what happened. Moreover, their residential tenure depended on the Pullman Company. Furthermore, they could never buy a home there. By the way, the community included a covered market but Pullman did not have a company store, but rented space in the market to providers.

It is a kind utopian thought experiment. One can have all these good things of life in return for giving up democracy.

George Pullman was no friend of democracy, having observed at first hand its practice in the 1850s and 1860s in Chicago where one corrupt political party replaced the other by turns with mayors and councillors each more venal than the other. The corruption at city hall, ensconced by the democratic process, was matched by the drunkenness, robbery, assaults, prostitutions, and drug-taking on the streets. One neighbourhood of two thousand residents had forty bars and fifteen brothels, and more. Ruthless landlords built tenements and extracted maximum rents for rat-infested hovels. Despite the taxes collected, the streets were mud baths with plentiful horse droppings. Schools and libraries were private with stiff fees. But here was vigorous democracy as the parties battled each other in the race to the spoils. The corruption included wholesale vote rigging. Some things have never changed in Chicago. There has always been a high turnout of voters there, especially among the dead who do not care for whom their vote is cast.

To most residents of Pullman and to the journalists and philanthropists who visited the town, it was superior. ‘To most’ but not all, because some railway workers wanted to extend the union to Pullman workers to secure higher wages and to increase the security of tenure in the homes they rented. There were occasions when workers who did not meet the Pullman Company standard of punctuality, sobriety, and good work were evicted from their homes overnight. In least one case the activities of a worker’s wife caused eviction. (Use you imagination to figure it out, Sherlock.)

George Pullman reacted to these union stirrings as a personal affront to his benign paternalism. There would be no negotiation; not an inch would be given. Cometh the fall.

The railroads were the site of much of the early struggle for unions, often led by the redoubtable Eugene V. Debs. I have discussed a biography of Debs elsewhere on this blog.

At the same time the ever-expanding city of Chicago, doubling in population every ten years, was encroaching on once distant Pullman. In time Chicago incorporated Pullman into Cook County though leaving the domination of the Company largely intact for another decade.

The collision course was laid in. The Pullman Company paid high(er) wages to attract and keep good workers as well providing all of the amenities of Pullman town for them and their families. But it was a business and when competition undercut the Pullman Company it unilaterally reduced wages while leaving the rents at the established level to get that 6% return on investment. When demand was high it expected unpaid overtime out of corporate loyalty. When the bottom fell out of the demand, the Company laid off workers and if they could no longer pay the rent, then they were evicted. The union movement found increasing interest from Pullman workers. By the way, Pullman did retain employees and sell cars at a loss at times before laying off staff. But the layoffs came.

The very kind of workers that the Pullman Company wanted, these were those most likely to chaff at the control of their lives and fates in Pullman Village. They were safe, sane, sober family men who would aspire to home ownership, who would want an education for their children and taken an interest in it, who would want a social life for the housewives, who would want family entertainment, who would want and expect job security. But George Pullman would never relinquish control of anything he owned, not one iota.

The result was the Pullman Strike that went from bad to worse. While the workers offered negotiation, the Pullman Company quickly resorted to force, and was shocked to find resistance. It spiralled out of control amid much posturing. Debs called every calamity a victory. George Pullman affected wounded pride. President Grover Cleveland sent in 12,000 Federal troops, three for every striker. (President Cleveland currently ranks in my book as the worst incumbent.)

The overkill of the corporate and political oppression galvanised public opinion against the Pullman Company. Religious leaders, newspaper editorialists, and even Chicago businessmen blamed the Company, not the strikers. George Pullman found himself ostracised among the business elite and that made him more stubborn. It became a test of wills, one he lost.

In the long aftermath, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the Pullman Company must divest itself of the town. The annual Labor Day holiday in the first week of September was one of the concessions to the union movement from this strike.

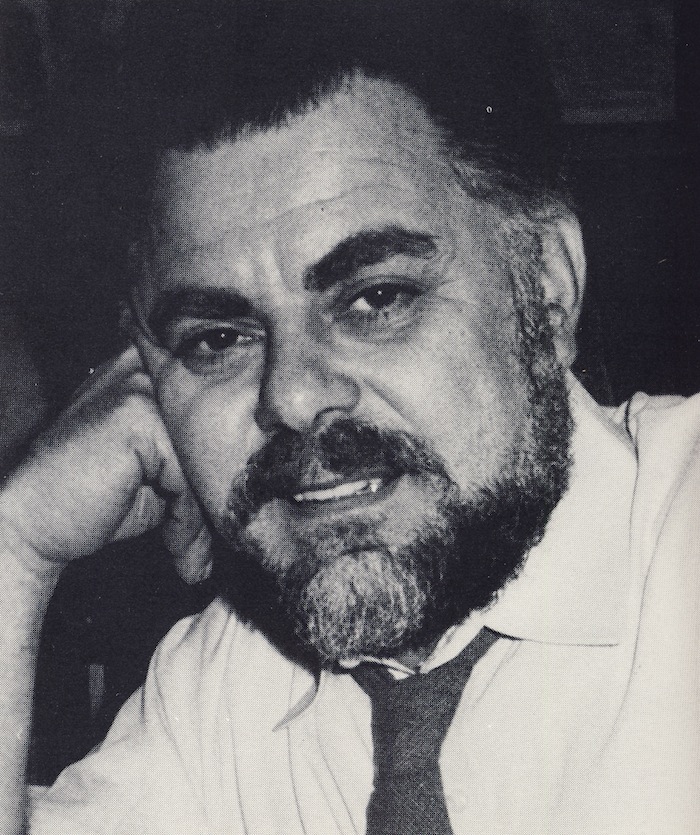

Stanley Buder.

Stanley Buder.

After a hiatus, the Pullman Company survived but was never the same again.

Nothing is said about race, but many members of the over-the-rail staff of Pullman were black. There is much else in the book about the business practices of Pullman which I found of interest. For that, read the book.

Skip to content