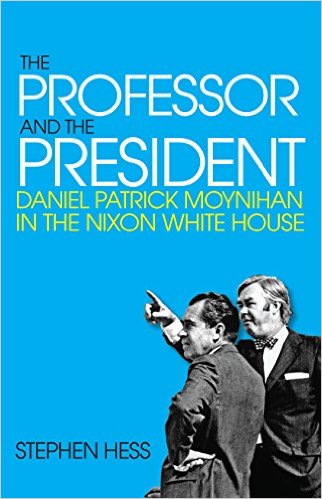

A memoir of sorts from the two years in 1969 and 1970 when Daniel P. Moynihan, with Hess as his deputy, served as President Richard Nixon’s chief advisor on domestic policy.

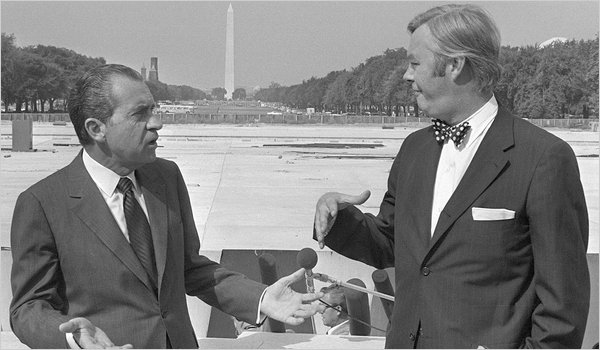

It was the odd couple: the president was a social conservative who courted to the right wing of his party to get the nomination and then moved further right to win the election joined with a high profile exponent of liberalism in American politics. Nixon ran to the right in 1968 first to secure the nomination from much more liberal Republicans like Charles Percy and that Hamlet of the Hudson Nelson Rockefeller. Then Nixon ran even further toward the right to undercut segregationist George Wallace’s independent campaign among those red of neck. Each time the message was simple and clear: law and order, cut welfare to zero, wind back the clock on affirmative action, stop integration by ending funding for its support, stack the Supreme Court with non-entities who would deny government intervention to support minorities…. That was rhetoric. It has a strangely contemporary ring to it, does it not?

In office the reality was this. Nixon wanted peace and quiet in the United States and he personally wanted peace and quiet in the White House. He was willing to buy domestic peace and quiet. Moreover, Democrats controlled both houses of Congress and seemed secure in continuing that. Nixon saw no reason to rile up Congress on domestic matters that he, Nixon, did not care about, nor to stir up the population by eliminating programs that had popular support. None of this could be done overtly for fear of alienating his electoral constituency which he would need again in four years. It was time for some legerdemain.

Enter Pat Moynihan. His credentials as a liberal in American politics were unassailable. He had worked for President Kennedy. He had advocated the cause of minorities. He supported all manner of social programs. His intellect was bright and he was a wordsmith, and he had other credentials, too, as a Professor at Harvard University. Robert F. Kennedy was dead, but Moynihan was his living spirit still flesh. Moynihan embodied from the bow tie on the Eastern Liberal Establishment that Nixon hated privately almost to distraction.

But it would placate Congress and confuse and perhaps divide his critics if he keep Moynihan close, and so Nixon appointed him as the chief domestic political advisor with cabinet rank. It was a masterstroke that won much breathing space for the new Nixon administration.

At the outset it seemed that Nixon’s administration would be dominated by two Ivy League professors, since his chief foreign policy advisor, appointed earlier, was Henry Kissinger, another Harvard professor, head of the National Security Council with cabinet rank. Remember that Kissinger had entered public affairs with Nelson Rockefeller, the most liberal of the Ripon Republicans (a phrase no longer used by the Grand Old Party). Are these two twin and each a deuce philosopher-king?

One of the interesting observation in the book under review is the comparison of the communities in the White House for domestic and foreign policy. While foreign policy is the preserve of the President, per the Constitution, and only two agencies figure in it, though they are the great and good Departments of State and Defense. In fact, with the appointment of Kissinger and the elevation of the position of Director of the National Security Council to cabinet rank, Nixon enlarged the foreign policy circle. It was still, however, a small circle. All the principals could sit around one small table, and a single strong personality could dominate the group, in this case Kissinger, even though he did not have the powerful Department of State and Defense at his back, he had the intellect and cunning to out manoeuvre them to influence Nixon. But that is another story.

In contrast the domestic policy community is vast and ill defined, but it starts with every other cabinet member, fifty state governors, and expands from there.

Moynihan saw an opportunity to dominate the domestic policy community with his own intellect. It would be a contest on two levels. The first was to get Nixon’s attention to domestic policy and the second was to displace his principle domestic policy rival, the economist Arthur Burns. The first step was simple and easy and had continuing implications. It comes down to real estate.

Thousands of people work in the White House and it has long since burst at the seams. Nineteenth Century broom closets have been converted to offices, hallways reduced in size to enlarge offices to shoe horn in more people, doubling and tripling up is the norm. The alternative was the Executive Office Building nearby. Moynihan opted to squeeze into a White House broom closet a few steps from the Oval Office, while Burns chose an opulent suite of rooms in the Executive Office Building. That was very nearly end of story. Game, set, and match to Moynihan. He was at hand instantly, and he made use of that.

In a way that says it all. The imperceptive Burns probably never quite realised it was a competition, and conveniently excluded himself. He further reduced his own influence by his ponderous class room manner. He could not participate in discussions ad lib. He could not debate submissions and never got to the point, if ever he had one, in less than forty-five minutes. If asked for comment in a meeting he would go away and write a lecture to deliver a week later. It was no contest. Nixon, in fact, began to interrupt Burns to ask for the conclusion, and then simply stopped inviting him to meetings. Moynihan excelled at debate and was always ready with an idea.

Getting Nixon’s attention was harder. The Cold War was very cold; the Vietnam War was very hot. The Middle East was on fire. Other trouble-spots vied for attention by more outrageous events.

But domestic policy could not be neglected. There were racial tensions and riots. Moreover, many Johnson programs were coming due for renewal and Moynihan was a genius at using these calendared deadlines to create some domestic policy for Nixon. He conceded some of the Great Society program to the dustbins, re-badged others, and merged many to serve up a diverse and responsive domestic policy. More importantly, he couched it all in terms Nixon could recognise and accept. That is, Moynihan played to the President, whose own background was one of hard times during the Depression. For two years the magic tape held.

Nixon came to like Moynihan who addressed him as an intelligent and well-meaning man, and did not act either the sycophant or supplicant. Sometimes Moynihan addressed complicated arguments to Nixon, in a rain of memoranda, on the assumption that Nixon would read and understand. These memoranda were often short, always witty, and usually tuned to the day’s headlines. Nixon liked being treated as an intellectual equal by this star from the Harvard firmament, just as the star liked being asked to advise on all manner of things, many beyond his remit.

The odd couple.

The odd couple.

It did not last because when all is said and done, well, Nixon was Nixon. He was unable and unwilling to ply Congress on domestic policy. By that I mean, Nixon was not someone who would court the support of anyone, still less in a policy arena in which he had no interest. Part of his dedication to foreign policy was because it was essentially the President’s chess game. He played the lone hand. At that he excelled.

To promote any domestic policy requires a president to woo, court, explain, cajole, coax, trade favours, entertain, persuade, the chairs of sub-committees, the chairs of committees, the party elders, the lobbyists, the press, individual Senators, faction leaders formal and informal, state governors, certain Representatives, and so on and on and on. This kind of endless dance was what Lyndon Johnson did better than anyone before or since, seldom idle and never alone when he could press his case on someone.

Nixon thought this kind of politicking without end led to compromises and bad policy, or so he said, but the truth is deeper. He just could not do this person-to-person persuading even if it was scripted and controlled. We can all speculate on why. Here is my take. Because of his background of penury he was too proud to ask others for help. To do so would be admission of weakness, and the weak are reluctant to admit it. There is also in Nixon a personal shyness that is another result of his upbringing that kept him in the family. That is my pop psychologising. (Yes, I know LBJ’s background was even more penurious and he had no trouble in seeking help.)

After the first few months of his presidency Nixon sharply reduced the time he spent in cabinet meetings, and made himself less and less available for appointments with anyone. Bob Haldeman who kept Nixon’s appointment diary noted that the President said and said often ‘I want to be alone.’ Yes, I thought of Greta, too, as I am sure did Hess, but he passed it in silence.

Nixon had to be alone with those yellow legal pads to think. When Nixon was thus isolated, as he preferred, Moynihan was a few steps away and would be summoned to be a one-man sounding board, who would speak freely in the privacy of the tête-à-tête.

Like Senator William Fulbright, Moynihan had made a Faustian bargain. He joined Nixon’s band on the pledge of loyalty and that he would not speak of the Vietnam War which was the biggest and hottest ticket for the incoming president. Moynihan kept his part of the bargain.

It lasted for two years and then Moynihan returned to Harvard. He paid a price for his association with Nixon and gradually went on to a political career in the Senate, taking the seat once held by Robert Kennedy.

The price was a loss of status among his Harvard peers for his dalliance with Tricky Dick. He never quite re-entered the Harvard Square club. Indeed, his association with the Nixon White House also damned him to many anti-Vietnam War protestors. The one chance I had to hear Moynihan speak, at a political science conference, he was shouted down, quite comprehensively, by such protestors.

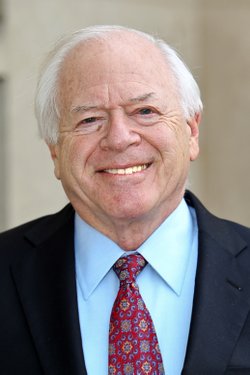

Stephen Hess has many other books, and I will certainly read more.

Stephen Hess.

Stephen Hess.

He is even handed, and lets the facts do most of the talking. He does, however, present most of this book in the present tense and I found that distracting, and I always find it annoying after I have been distracted.

Skip to content