In sum, this book, despite the subtitle, offers very little about the boy, adolescent, young man, or adult. Hammarskjõld was born to the purple. He grew up and lived most of his life to twenty-five in a palace in Uppsala, that being the official residence of the provincial governor, his father. However the book is excellent on his tenure at the United Nations.

He had little international experience but some on a Marshall Plan Committee as an economist. Because Swedes did not receive Marshall Plan monies they were trusted to allocate and manage it. Hammarskjõld had been an economist at the Bank of Sweden and done some international negotiating.

There is nothing about his life, experiences, or attitude to World War II. Why and how he learned English is not discussed. He also spoke German.

Trigve Lie from Norway was the first Secretary-General and he had taken sides in the Cold War, though he wanted a second term, the Soviet bloc was alienated.

The next Secretary-General had to be a neutral. The less experience the better, so as not seen to be committed or to have baggage.

Hammarskjõld entered as completely into the job as if he were entering a monastery. He sworn and oath to the Charter which thereafter he carried on his person for ready reference, yes, but also as a document to venerate. There is a spiritual quality to his commitment.

No women. No significant other of any kind. Though many rumors about homosexuality.

His life was monastic. He got by on three to four hours sleep most of the time. In a deep crisis like the Congo, less and in quiet time little more.

At the United Nations he relied heavily on Ralph Bunch, first for internal administration and management and later as a deputy diplomat. (Maybe I should read about Bunch, this extraordinary individual.)

‘Markings’ Hammarskjõld’s personal notebook reveals the spiritual inner man who communed with the writings of medieval Christian writers. Much of this book and consists of musings on Hammarskjöld’s musings in ‘Markings.’ Hundreds of pages. All too much musing and not enough narrative.

Hammarskjõld had tall poppy cutters in Sweden who made career out of criticising him. Newspaper editors, who extended their animosity to berating the posthumously published ‘Markings.’ It is good to know that Australian media ethics are in such good company in the gutter.

Some of Hammarskjõld’s speeches are fabulous. Lucid, clear, targeted at the next step, infinitely patient, aware of the pressures on others, but punctuated with some elevated words to inspire. He seems to have gotten better and better at this rhetorical skill in the UN. It is not something he had any previous experience or preparation to do. They read well, though I have no idea how he delivered them.

Hammarskjõld more or less created the role of the international civil servant, and reflected on that, especially in the in-house speeches and reports to UN staff.

He had some successes in meditating conflicts, like the Suez Crisis in 1956. Then came the big one.

The Congo consumed him even before he died there. The endless fragmentation, the intervention of Europeans to support the Belgians who did not want to leave, and the tribal and regional violence armed by the Soviets, the CIA, Belgians, South Africans…. were let loose. The single Congo became two, then three then four entities each with its internal constituencies, that is tribes, and external supporters, and all armed to the teeth.

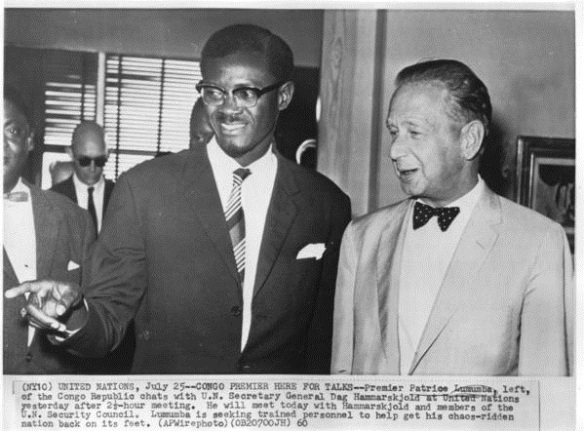

Patrice Lumumba is the most interesting of the characters in the Congo. He was an articulate idealist who seemed to have been able partly to bridge some tribal differences. He was a rabble rouser on radio and in person. But he had no ability to work with others in committee, completely useless as an administrator, and he had no competent second to cover these things. He was a front man only with no band behind him. He could arouse a crowd but he could not lead it anywhere. His only message was to reject the Belgians and as they left the vacuum was filled.

Dag Hammarskjõld and Patrice Lumumba

Dag Hammarskjõld and Patrice Lumumba

There is much about Hammarskjöld’s death. Hear-say, secondhand, and some alleged eye witnesses who feared to speak at the time and who now cannot shut up thirty years later. All the so-called doubts seem to me to be speculation. If any other death was raked up thirty years later it would be the same.

There was a lot of mission creep in the Congo, despite his efforts to limit it. It went from peace-keeping to, since there was no peace, peace-making.

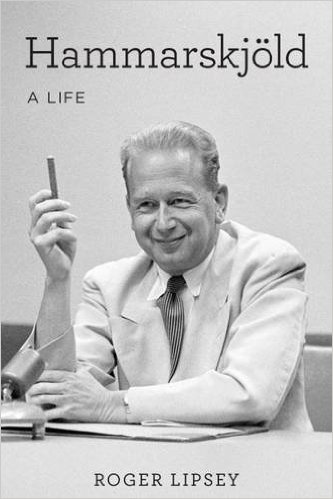

Roger Lipsey

Roger Lipsey

The book is far too long and there is just too much musing for a biography. Moreover, there is precious little biography of the boy become man in Sweden. It is a reflection on Hammarskjõld’s tenure as Secretary-General, and it is good on that. But despite the many musings on Hammarskjõld’s musings, I never did feel I was getting close to the inner man. I did feel impatient more than once.

The dissolution of the Belgian Congo was a grim story that occupied the television news every night, and it consumed a lot of good men and women. When I looked for a biography I found many on Hammarskjõld’s death, conspiracy theories, ‘now it can told,’ sort of titles that seemed to be ghoulish attempts to capitalise on his death. All in the spirit of Jim Garrison (for president) on JFK.

Skip to content