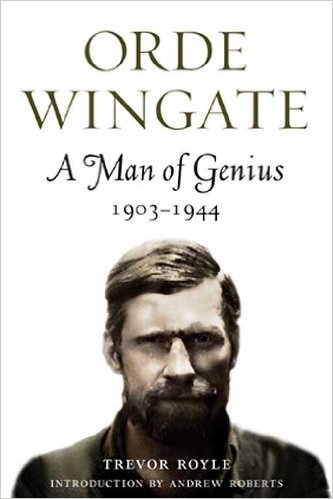

File this under leadership. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk suggested this title to me and I downloaded it onto the Kindle. I had a vague recollection of the name Wingate from Burma in World War II and before that Palestine. Emphasis on the vague. There in those places he was a solider, but who he was and how he came to be there and what he did there, these were unknown to me.

The author’s many careful efforts to make Wingate likeable or admirable fail. Selfish, egotistical, opinionated, volatile, contrary, argumentative, self-absorbed, vain, destructive, delusional, contradictory, and arrogant, these things he was. Genius? Well, how would a mere mortal know?

While his family had money, most of it was given away to charities converting heathen Africans to Christianity. His parents were fervent Christians who preferred prayer to coal fires in winter, prayers to doctors, Bible reading to schools, and waited every day for the second coming of the Saviour.

Because the devil is devious, his father occasionally beat his oldest son, Orde, as a preventative measure. One of Orde’s sisters wrote an angry and bitter memoir of their childhood in which she describes wearing all the clothes there were and watching the fingers turn blue in the cold. The food, well there was some, but words failed her when she tried to describe it.

The Wingate children were kept at home mostly to prevent sinful contact with corrupt beings, that is, other children, while waiting for the second coming. It goes on like that. It is no wonder he became such a nutter. The wonder is that anyone could put up with him. Well, in fact, few did.

The one allowance his parents did make at home was servants, and Wingate led the rest of life on the assumption that there were nameless servants following behind him to clear up the messes he left. These were many. Some well beyond the pay grade of a domestic service.

His father had been in the army (while waiting for the second coming) and as the oldest son Orde followed in those footsteps.

In anticipation of the second coming, at first the young Orde did not apply himself, but in time he did so. The author is unsure what the catalyst was, except perhaps to prove himself to his father. He studied to gain entry to the artillery, and got it, largely thanks to the intercession of an uncle with influence on the General Staff. Many other intercessions followed in his career, as he lurched from one mess to another, usually of his own making.

Wingate spent an inordinate amount of time bewailing the establishment and its many failures and corruptions, all the while advancing his career through the influence of that very establishment. The author draws some veils over the trail but it is pretty clear that he made his way thanks to the string-pulling time after time.

There is no doubt that once he gained a sinecure he worked hard at it and when he concentrated he had considerable ability, but these periods of application were few and far between. The point is that others better suited and more willing to work through channels were denied the place(s) he got, while he denounced the very establishment that made him.

He had a self-destructive streak, as many young men do, and his was perhaps redoubled by that prospect of the second coming, and he blithely extended his risk-taking to the men under his command. He served in the Sudan in the 1920s, and led patrols against various tribes, whom the author invariably describes as rebels. Hmm. It is their home and the Brits were the invaders.

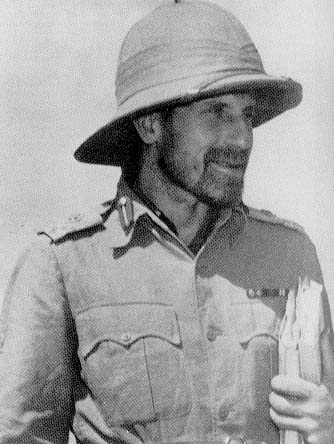

Orde Wingate

Orde Wingate

Further wangling by relatives got him posted to Palestine the 1930s where he became an anti-Lawrence of Arabia. Though a serving British intelligence officer, he became more Zionist than the most ardent Zionist. Another volte-face, and again the author cannot quite pin down the trigger. I suggest it was another one of his delusions of grandeur. Gideon come to liberate Zion.

He was a good intelligence officer. A quick study, he learned Arabic and then Hebrew, and set up the routine translation of Arabic and Hebrew newspapers, pamphlets, lists, and registers that served the British well in the Middle East.

He also betrayed the trust of his position by passing much of the intelligence he saw along to Zionist and Jewish interests. This is reminiscent of the flippant betrayals of Kim Philby, who never gave treason a second thought. Neither did Wingate. Neither counted the bodies because of their treason. When Wingate’s treason became known, it was hushed up on the grounds that to reveal it would be bad publicity. He prospered where another officer would have been courtmartialed and cashiered. This is a recurrent theme in his career. A giant debacle is covered up and he is promoted. Wingate learns that he can do no wrong, and continues in the same vein. (The author does not use the term ‘treason’ nor compare him to Philby. That is my work.)

He got away with behaviour that few others would do, let alone survive, and he thereafter prospered. He struck enlisted men more than once, and was not even reprimanded for it. Indeed he got away with so much that the rumour spread, and became self-fulling, that he had a powerful protector in the hierarchy. He then got away with even more childish behaviour that is all too tiresome to review. It is a reminder of the frequent inability of organisations to handle unsocialized miscreants, like the villains who embezzle millions from banks or the doctors who experiment on patients in hospitals.

His early efforts at combat were disastrous for those under his command. Though the author skirts around it, this reader concluded that Wingate had no grasp of small arms tactics and managed to get his men into a cross-fire of his own making. Rather than be reprimanded, he got a medal for that action, and four dead. That’s the pattern.

He did learn from the cross-fire, and later stressed infantry tactics, something the author seems to think is a sign of his genius. After leading his men into a self-made trap, he then read the field manual. Genius that.

Again despite the author’s delicacy, it is also pretty clear that Wingate’s raids on ‘Arab rebels and gangs,’ as the text styles them involved murdering women and child, preferably in their sleep. These crimes the author puts down to his enthusiasm. ‘Crimes’ is my word, not the author’s.

His personal life was as chaotic, reckless, and destructive as his professional life. He wooed a young woman who waited patiently for him for six years (biological clock ticking) while he was promoted in the Sudan, and then he jilted her without a backward glance.

He threw her over because at thirty-one he had fallen in love with a fourteen year old girl. You read that right. I skipped through a lot of this quickly and I may have the ages slightly wrong but he was twice her age and she was underage. More waiting, and eventual marriage.

Throughout these campaigns he carried a Bible at all times and often referred to himself as Gideon. He meant that literally.

During World War II in Somaliland and Ethiopia against the Italians and Burma against the Japanese it was more of the same on an ever larger scale. By the time of his death he was a major-general, hard though that is to believe. In Burma he concocted wild schemes that got a lot of men killed to little strategic purpose, as far as I could see, despite the author’s efforts to dress it all up. On this point more below.

He also got himself killed. Fitting in a way, though as usual he took others with him. He was flying around inspecting the units that had the misfortune to be under his command, scattered through the jungles of northern Burma. The aircraft was proving to be difficult and the pilot discussed it with ground crews at several of the places they visited. But the pilot did not venture to tell Wingate the timetable must be delayed while the plane is fixed or replaced. Instead the pilot pressed on and the plane crashed. He did not dare tell Wingate whose volcanic temper was widely known.

Toward the end the author suggests as evidence of Wingate’s genius this comparison. It refers to his efforts in Burma to get behind the Japanese. Here is the comparison: Imagine, if a fortnight after the Allies’ Normandy landings, the Germans had inserted by gliders two divisions in Kent between London and south coast to block traffic, create a political crises, and deflate morale.

It is a striking image and it gave me pause. Briefly. Of course there is no comparison of Kent with the jungles of northern Burma, but more important, dropping two divisions of troops into the middle of nowhere was hardly a strategic move. Had the Germans done that, Dwight Eisenhower would have been unable to believe his luck. I say this with confidence, because Ike recognised from the start that the German offensive at the Bulge was crazy. True, it would do a lot of damage but not accomplish anything, because there was no strategic objective. Nor was there one in northern Burma.

Trevor Royle

Trevor Royle

I read it on the Kindle. The book is well written and to the point. My complaints are about Wingate, not the book. In fact, the book is very well judged, and while the author is clearly trying to rehabilitate Wingate against his many detractors, he provides plenty of information to allow a reader to decide, and I did. Put me in the detractor’s camp.

Skip to content