The greatest Finn, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1867-1951), spoke nearly no Finnish. That is just one of the paradoxes of the man and the state and nation he made.

Mannerheim’s family traced back to German Hanseatic traders who settled first in Sweden when it was a dominant power and then among the Finns where there were commercial opportunities. Mannerheim is a derivation from Mannheim, as the spell-checker keeps insisting. Mannerheim had no interest in that Teutonic past and came to view Germany as an enemy. Yet late in life he made an alliance with the devil himself in Berlin, Adolf Hitler, to save Finland from a worse fate. On that. more later.

Let’s slow down and get back to the beginning. He was one of many sons in a very well off family. His grandfather had been a Count and his father was a Baron, and Mannerheim himself was a Baron. That sounds grand but in the hierarchy of his time and place it was near the bottom of aristocracy, money or no.

As a boy he was unruly, as children may be, and loved the outdoor life, especially with horses. He was sent to military school for the discipline and Mannerheim liked the idea because of the sports and horses in the cavalry and eventually entered one.

For centuries the Finns, together with Norway and Denmark, were ruled by Sweden from distant and imperious Stockholm. This Greater Sweden eventually lost a war to Russia in 1809, and Finland was created as a dependency of Russia. In fiction it was an independent Grand Duchy, whose duke just happened to be the Czar. By that fiction local freedoms and practices continued. For example, Russia made no effort to impose military service on Finns, and permitted local militias to keep the peace. Censorship and taxation were light. The Grand Duchy of Finland served as a buffer to any future Swedish aggression, and a staging ground should Russia take the initiative.

Mannerheim’s family was Swedish, that was the maternal language, though resident among Finns for centuries when he was born. (Swedish remains an official language in Finland today.) He grew up speaking Swedish as did most of the resident aristocracy.

After several false starts, he entered military school in Russia, and there he stayed for the next thirty years. (Let that sink in. Thirty years a Russian.)

Young Mannheim, riding crop at hand.

Young Mannheim, riding crop at hand.

He made a career in the Czar’s Russian army. While many Russian officers took their place by birthright, Mannerheim worked for his, and once there, he worked at it, unlike so many others. Accordingly, he rose through the ranks. He was, remember, a Baron, and there was no social barrier to promotion.

When Nicholas II was crowned, Mannerheim was selected as one of four officers who stood an honour guard on the steps of the church, a singular honour for someone who spoke Russian poorly with a heavy Swedish accent. The one barrier he faced in the army was speaking Russian, but he worked at that with the same application he showed to much else.

He married a Russian aristocrat who soon found him boring and took herself off to the south of France with their two daughters. There was little subsequent contact. She had supposed they would live in St. Petersburg while he became a staff officer, but to be promoted he had to have field commands, in one back-water after another. This book is silent on any other sexual interests he may have had.

When Russia and Japan fought over the metal and mineral riches of Manchuria in 1904-1905 he gained combat experience. He learned there that cavalry had no chance against the machine gun, and he loved horses too much to see them slaughtered to no point. Thereafter in his mind the horse was a means of transportation, not a weapon. This was not the common reaction and made him stand apart from other officers who still favoured the cavalry charge. Nonetheless he weathered his baptism of fire and gained recognition and promotion because of his cool head and clear thinking under fire.

A contemporary cartoon on the bloody conflict, showing Russia and Japan courting Manchuria.

A contemporary cartoon on the bloody conflict, showing Russia and Japan courting Manchuria.

There are estimates of 70,000 Japanese deaths, 120,000 Russian, and 20,000 Chinese by-standers in the eighteen months of combat. Teddy Roosevelt brokered a peace treaty.

The theatre of operations.

The theatre of operations.

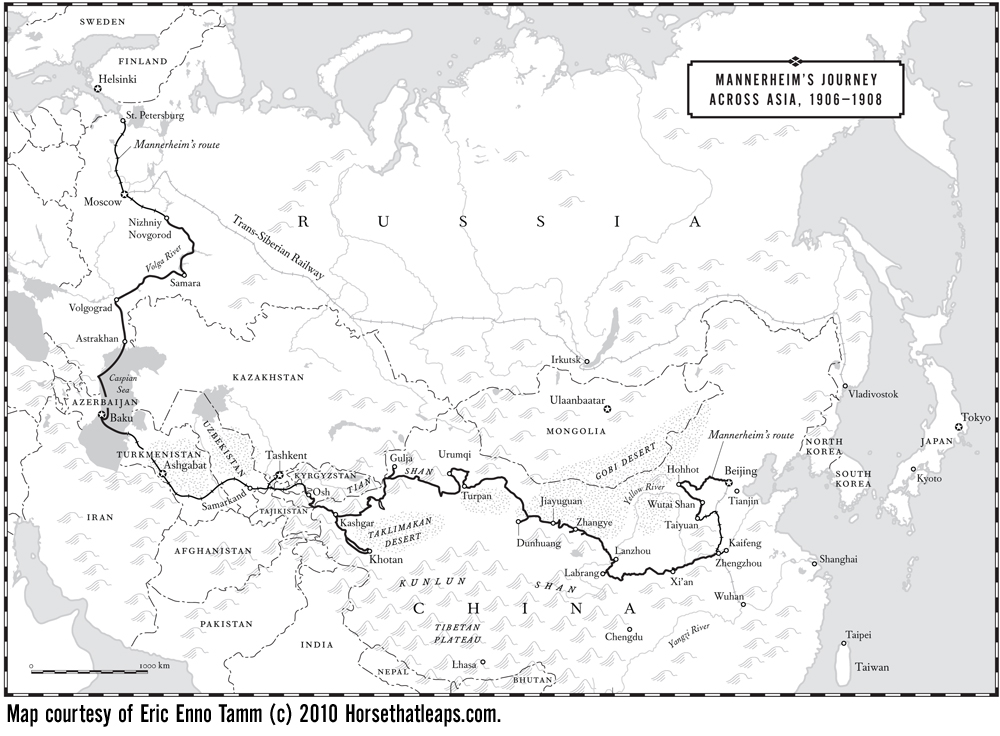

Later when the Russian General Staff wanted to gather intelligence about the far reaches of Western China, that is, Sinkiang, the duty fell to him. Mannerheim travelled for two years, filling notebooks with copious details about roads, mountain passes, fodder for animals, obstacles, fords in rivers, attitude to foreigners, capacity of the central Peking government to act in these extremities, the effect of altitude on man and beast, the grades of ascents, the frequency of avalanches, and more. He was a meticulous notetaker, a keen observer, and inquisitive questioner, so much so that Chinese authorities more than once interrogated him as a spy but his cover as a scientific explorer held. When he reached the Russian legation in Peking, it took him two months to write a report based on his notes. It was later published in two volumes.

Mannerheim’s Asia route.

Mannerheim’s Asia route.

Leaving aside the myriad of details, what is most impressive about this exercise is, first, that he did it largely unaided, and, second, that he realised the area had no strategic value and said so. At best a Russian incursion there might draw off Chinese men, material, and attention from the real prize, Manchuria. He said as much in his report.

He was offered another such mission but respectfully declined because he was anxious to return to field command to continue his way up the promotion ladder. In 1914 when the lights went out all over Europe he was a Major General in the Russian army and led troops into combat against the Austrians in Rumania and Germans later in Poland.

While he had been in the Orient, the Russian hand on Finland tightened. Taxes increased. Traditional freedoms were curtailed. Censorship increased. The imposition of the Russian language grew. Mannerheim’s correspondence with his large clan of brothers and sisters made him vaguely aware of this change. But there is no doubt he felt torn between a maternal interest in Finland and his personal oath of loyalty to the Czar.

Russia had been home to him for thirty years and had provided him with many more opportunities than Finns could have. He knew far more Russians than Finns, apart from his own family who, remember, were Swedes with little in common with the locals Finns among whom they lived. He spoke nearly no Finnish.

By early 1917 the wheels were falling off the Russian cart and he was caught up in it, like millions of others. He despised the mob he saw in the Bolsheviks, there was never a democratic sentiment in this man, and took leave to recuperate from war wounds in Finland, passing through the St. Petersburg station from which Lenin emerged.

With Russia collapsing, Finns declared themselves a country in 1917 and set about making one. While autonomy appealed broadly to Finns, there were many differences over the specifics. Some wanted to remain close to Russia for protection, while others wanted an entirely new course. On another plane were those who wanted a Bolshevik revolution in Finland to displace the established order of aristocracy and church, and others who wanted to fortify those institutions and practices against any and all threats. In time these divergent interest boiled down to conservative Whites who wanted a Finland independent and radical Reds who wanted a Soviet, which might well be aligned with Russia. (See Craig Cormack, ‘Kurrikka’s Dream’ (2000) for the Red side of this coin, with an Australian echo.)

The self-appointed Finnish Council’s first priority was to define and defend the territory of Finland, including the Karelian Isthmus, from predators, of whatever flag. Defence required an army, and army had to have a general. A few streets away sat a Lieutenant-General. This general’s exploits as soldier in Manchuria, explorer in Sinkiang, and general on the Eastern Front had been a matter of some national pride among Finns in the preceding years.

The book is very well researched and carefully argued. It begins with a survey of existing biographies of Mannerheim which is lost on this reader but affirms the care of the author in situating the work. It is based on extensive examination of Finnish, Russian, German, and Swedish sources, including Mannerheim’s own notebooks and letters. Altogether it seems to be a definitive work of the public life of Mannerheim. I could not find a picture of the author on the web.

Note, Mannerheim took it upon himself to convert the cavalry under his command to mounted infantry, and only the intervention of Czar at some point saved him from a reprimand for such an initiative. As World War I approached the Russian army was spending more on sabres for cavalry than machine guns, according to Barbara Tuchman in ‘The Guns of August’ (1962), discussed elsewhere on this blog. As journalists are always criticising the last war, so generals often prepare for it.

Skip to content