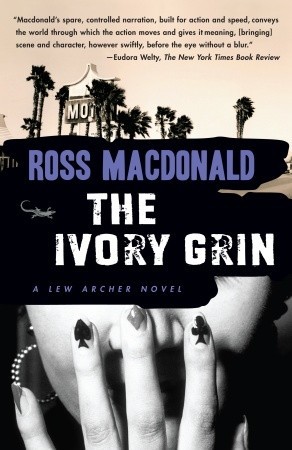

A gritty tale of unrequited love(s), madness, and sacrifice from the stylist of noir krimis. Raymond Chandler had a ear for dialogue, while Ross Macdonald has a jeweller’s eye for descriptive metaphors and images. Lewis Archer is his avatar.

While the novels obey all the conventions of the genre in its time and place, it also turns them inside out. The PI’s boredom counting flies on his office windrow is interrupted by a femine fatale, as required, but this one, despite the diamonds and furs is barely a femme at all. A very mannish woman is she. Archer’s emphasis on her lack of feminine qualities is partly the everyday sexism of the era but it also turns out to be a pivot in the plot.

As always with Macdonald, everything from the color of the sunset to the hats impart texture, reveal character, and unwind the plot. Nothing is ever wasted in his novels.

This is a triangle of three families, locked together by one of the offspring. Bess is literal when she says she loved him to death. Lucy, the loyal nurse, sees more than she ought and cannot get out of the vortex. That manly woman is normal compared to her brother, who has a gun. Assorted other lowlifes pass by, but the worst of the lot is the quiet suburban doctor.

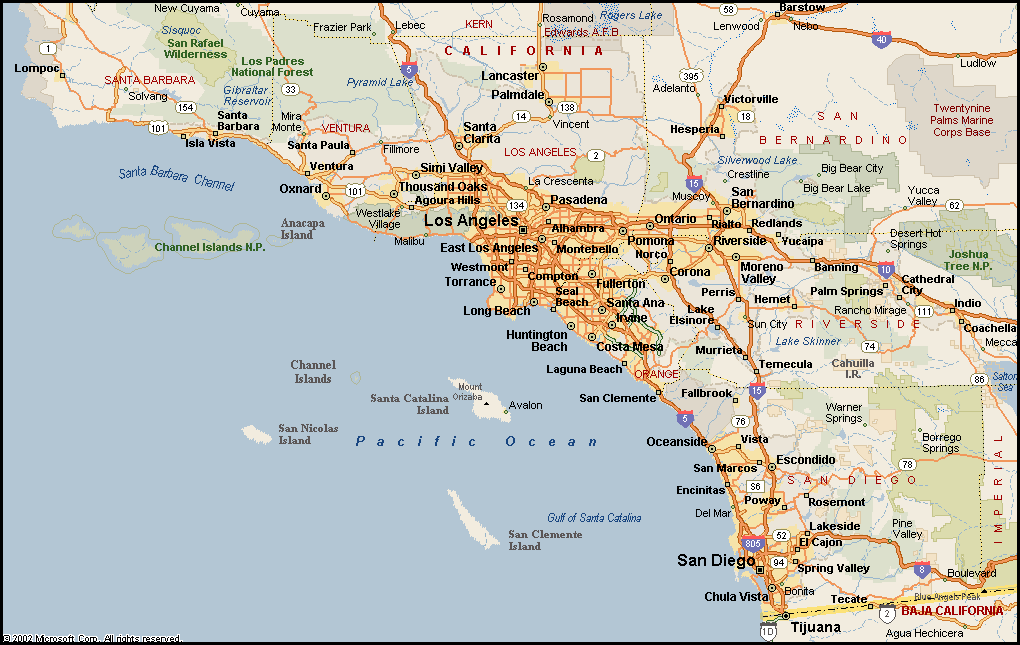

Archer country

Archer country

There are some innocent bystanders along the way, Alex the love-sick boy who pines for nurse Lucy and the love-sick girl Sylvia, who pines for playboy Carl, and who becomes in a convolution of the plot Archer’s client.

I still have the paperback copy of this I read In the 1970s but I re-read it on the Kindle. I turned to it to find something to read after a series of misfires with annoying, self-indulgent, padded, and pointless krimis. If only Jane Austen knew what she had spawned when she told would-be writers to to write about what they know. Far too many only know the IKEA catalogue. Why continue the search for quality when I know right where it is.

Sometimes Macdonald’s metaphors and images come so thick and fast that they create a traffic jam in the reader. Sometimes the psychologizing gets in the way of the momentum of the story. But these are the prices of admission.

Archer is named for Sam Spade’s deceased partner, Miles Archer, who believed in fifty dollar bills.

Macdonald’s krimis are hard boiled in that they are unsparing In word and deed. The villains are villainous with little of no veneer. Often the mystery is less who dun it than why dun it. That is the psychological depth that distinguish his works.

Ross Macdonald, who spelled his name with a lower case ‘d’ though the spellchecker disagrees.

Ross Macdonald, who spelled his name with a lower case ‘d’ though the spellchecker disagrees.

This one is the fourth of eighteen Archer novels over a thirty year period.

At least one of his krimis had a rave review on the front page of the ‘New York Times.’ The book was ‘The Underground Man’ in 1971 and the reviewer was that southern novelist of note Eudora Welty.

Yet none of his novels was ever awarded a paramount krimi prize like the Edgar. Figure that out, Mortimer.

Had I to pick one, it would be ‘The Blue Hammer’ in 1976, his last completed novel. I recall still how eager I was to get it and to read it, taking it with me when I went jogging to read a few pages while catching my breadth.

A mature work. in it he is not trying so hard to crowd in metaphors and there is less speculative psychologizing by Archer, while retaining the descriptive richness, the psychological depth, the ambiguity of motivations, and the equilibrium of the moral balance. In his books, unlike life, the world bends towards justice of a kind.

Perhaps Macdonald wrote one book eighteen times, as has been said, the same story of twisted love, divided loyalties, wayward offspring, mental imbalance, irresponsible parents, each magnified by a the glare of money in the prism of California sunshine that blinded the individuals to their own deeds.

By volume eighteen the biggest mystery is Lewis Archer himself about whom the reader learns almost nothing. He is a lens that reveals the story of those around him. By his actions we can see he is an inveterate loner, but one who warms readily to some women he meets for their physical and intellectual charms and vulnerability; he is dogged, and hard working. He wears a hat which he sometimes takes off. In one story we note he drives a light blue car, in contrast to his dark blue mood. At least he has a name, unlike Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op.

There is less about Archer in the eighteen titles than there is about Philip Marlowe in one of Chandler’s books. Archer has no backstory. The reader is not manipulated into feeling sorry for him. Why should I, he certainly does not feel sorry for himself.

Archer reports on the dirt under the carpet of the American Dream in the golden sunshine of Southern California, and it is very dirty. Yet he meets honest people whom he likes, and some he even admires. Say in contrast to the BBC’s Christopher Foyle whose world is populated entirely by liars, cheats, and murderers, often dressed in gold braid with aristocratic titles and important government jobs, Foyle’s is a world without hope, but Archer’s world has hope, and that is what keeps him going.

Skip to content