To fathom Trump Donald’s loyal following turn off the television talking heads for whom last week is the long term perspective and the pubescent professional worriers contributing to op-ed pages. Far too much of news reporting is journalists talking to each other, and journalistic analyses occurs when they write down their conversations.

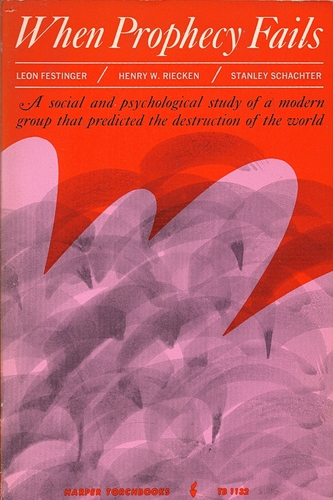

Turn instead to the bookshelf and find Leon Festinger’s ‘When Prophecy Fails’ (1956) a superb empirical study of a cult, placed in the context of the many end-of-days prophecies that preceded it.

His finding, at its simplest, is that believers reduce the cognitive dissonance between two contradictory beliefs by affirming one, usually the existing one, untouched by contrary facts. Primacy, the belief that came first usually, but not always, prevails. The belief that comes at the higher or highest cost may be the one to prevail. Cost can be psychic, monetary, social, moral, and more.

When the prophet predicts the second coming of Christ the Saviour at 3 pm on Thursday 3 April 1925 and nothing happens on the day; the failure of the Advent, the ridicule of outsiders, these combine to strengthen the commitment of the prophet’s followers, rather than to weaken it! Failure is just another path to success. Such believers redouble their own efforts after a failure, rather than scrape it.

Counter-intuitive, but nonetheless quite true. Yet it makes sense.

If the believer has sold his home, shed a pet, moved his family, endured ridicule and abuse from friends and neighbours, overcome family dissent, and more to be ready on 3 April, all the costs have been sunk. Retaining the belief in face of failure on the day is relatively easier than admitting the colossal error in the first place. The cost of continued belief at the point of disappointment is little compared to that already endured.

Sports fans will recognise this phenomenon in themselves. For years I gave freely of my interest, support, time, and personal identity to follow a certain sports team. Year after year, I supposed this would be the year in which the team blossomed. Pathetic losses, self-defeating trades, crazy management decisions, lackadaisical play, the clear preference of the players to be elsewhere, all these I ignored in favour of the larger goal. Facts bounced off my conviction.

This is the story of an individual, but the phenomenon can be general, as in the case of the all of the fans of the Chicago Cubs who form a cult of sorts.

According to Festinger, the greater commitment followers make to a prophecy (and its prophet) (or team) the less likely they are to quit when contradicted by facts.

Followers with an enormous sunk-cost in the prophecy will instead rebound from failure somehow. Yes, of course, some will drop off, who were never very committed, but the interesting ones are those that persist, and they are many. Surprisingly many. The ‘somehow’ is by denying the contradiction, suppressing the dissonance. This what psychologists in another context call denial. Festinger transferred that concept to social relations.

One upshot of this suppression of dissonance is that the more abuse heaped on believers, the more contradictory evidence is pushed at them, the more they are criticised, then the more tightly they will cling to the belief. Ergo the social media and other attacks on Trump Donald’s followers entrenches their conviction, rather than erodes it.

Most of us, most of the time do not hold any beliefs so firmly as to precipitate dissonance. We may believe something to be true, and then discover evidence to the contrary and qualify or reject our earlier belief, and move on. That is how it works in general. I believed for years that … then I read a few documents that showed otherwise, so I stamped ‘mistaken’ or ‘false’ over that belief and removed it from my mind, so to speak. But a believer with enormous sunk costs, might, when confronted by the documents, instead reject them as forgeries, as the seed of a conspiracy, as irrelevant, as only to be expected from paper pushers.

To judge from the media representations, many of Trump Donald’s most enthusiastic supporters are new to political mobilisation. Never been to campaign rally before. Never spoken up for a candidate. Never took part in a demonstration before. Never been registered to vote for a primary election. Never voted before. Never…. Perhaps many of these individuals have absented themselves from the political system with the prophylactic cynicism most of people use now and again about politics. To put that carapace aside and engage with the political process is an enormous commitment for many such people.

To register, to go to a rally, publicly to endorse a candidate, to declare oneself a Republican, each of these is a big commitment, and it will take a lot more than the mockery of social media types to dislodge it.

Indeed the mockery from such types is kerosine on the fire of their belief. It vindicates the belief that dark forces are working against them and their kind.

Festinger’s two stooges became participant-observers in a group, let’s call it a cult for reference, whose members believed they were communicating with beings from outer space. These spacemen told them that on 20 December a great flood would devastate much of North America. On the 19th the Spacemen would land and evacuate all those who gathered at a certain location. I said ‘stooges’ to be provocative. They were hired assistants.

Believers sold their houses, moved near the location, took pets to animal shelters, sold cars, stock piled food and water, sold clothes and generally divested themselves of possessions. Several quit jobs to be free to prepare. All of this caused dissension in some families and much ridicule from neighbours and friends. There were about a dozen hard-core believers and a few others at one remove in the group.

The designated date came and went without devastation.

Failure did not dishearten the hard-core members, but rather stimulated them to proselytise others. This is the phenomenon that Festinger found the most remarkable. Failure led to redoubled efforts.

The account of the cult and its members is measured and respectful. While many of their beliefs and actions seem wacky the reporting is absolutely deadpan without a whisper of humour or irony. Indeed, a reader suspects Festinger grew to like some of the members, and to admire their courage in the face of derision.

A strongly held belief, in the name of which considerable sacrifices have been made, will endure even the most obvious failure. When a high price has already been paid, the payer will stick with it. We have all done something like that, made the best of a bad lot.

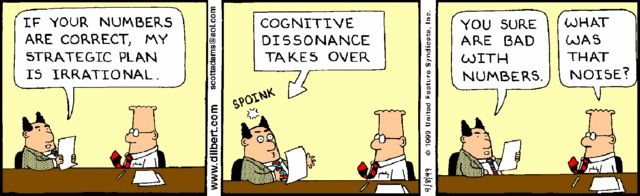

Dilbert knows.

Dilbert knows.

Rather like a Ted talk. So much show, so little go that one dare not admit it.

Rather like a Ted talk. So much show, so little go that one dare not admit it.

Here is another parallel analogy. British Bomber Command in World War II has been a sacred cow for two generations. Though it contributed virtually nothing to the war effort and compiled astonishing casualties while slaughtering innocents, it has been above criticism. Why? Those casualties, that is why. So many men were killed that it had to mean something, despite the facts. On the corruption and incompetence of Bomber Command see Freeman Dyson, ‘The Children’s Crusade.’

When I re-read ‘When Prophecy Fails’ I thought that this kind of research would not likely be done today. It might not even be on the curriculum today. Why not?

Leon Festinger

Leon Festinger

The barriers of privacy and informed consent would make it either hard or counterproductive to examine such a sect as a participant-observer. Explaining the nature and purpose of the investigation to those under study would undermine it, yet the procedures recommended by the American Psychological Association, for one, do just that. This is the legacy of Stanley Milgram. Imagine how a research ethics office, asked to approve such a study, would react. Shudder!

Funding bodies spend all the money on other, smaller more controlled studies before one such as this would get a look. The small studies will certainly be done, whereas something on this scale is far less certain. That is, most social psychological studies there days are done with undergraduate students in classrooms (called laboratories to sound scientific). I have read scores of such studies in the last few years, and they are inevitably done in class. These are captive subjects who are far from representative of anyone else, but we have collectively decided to ignore that.

There is not a single equation in this study which relies entirely of narrative, i.e., qualitative data. Imagine the criticisms an anonymous journal reviewer would level against this kind of work today. The boom would be lowered. This absence of the quantitative makes me wonder if it would even be assigned, against the competition of so many quantitative studies of this and that.

More generally, the career incentives are so short-term that a broad gauged study that takes time to do the field work would invite a negative report by a research manager. I have seen it happen in a partly analogous case where a scholar who had been publishing fine books every three to five years was questioned ay an interview about why he so unproductive in the intervening periods! In that case, wiser heads prevailed, but for how much longer?