Franklin Pierce (1804-1869) was the fourteenth president of the United States, 1853-1856.

His father had been a New Hampshire militiaman in the Revolutionary War, and his two older brothers had carried muskets in the War of 1812 against Great Britain. Pierce grew up in a family that was among the founders of the new nation, and self-conscious of it.

His war leadership put his father into the governor’s chair in Concord, and the boy Franklin accompanied him on his rounds of meeting voters throughout the Granite State. He was suckled on politics.

He was an indifferent student, preferring the recreation of an outdoorsman, killing: hunting and fishing. He was clean cut and of pleasant appearance. Not so handsome to make men jealous but nonetheless attractive to women. He also had learned, observing his father, how to get along with people with whom one had little in common.

The political parties at the time were decaying and re-newing. In the first generation of the republic the two alignments had been the Federalists, who favoured a strong central government for defence, supported by taxation versus the Anti-Federalist, who favoured ‘that government which governs least.’ Among the Federalist was Alexander Hamilton and among the Anti-Federalist was Thomas Jefferson.

The cleavage between these two blocs was partly regional with New England and the mid-Atlantic states generally favouring the Federalists, while the tidewater and southern states were the home of the Anti-Federalists.

Because they lived by trade, the Federalists states wanted the central government to impose tariffs on imports, build harbours and roads, and guarantee banks to further their business interests.

The Anti-Federalist feared these powers would disadvantage their plantation economy based on slavery. They were also mindful that the Constitution’s provisions for slavery were tenuous, and feared a strong central government, dominated by Northerners, would undo some of the Constitutional measures sheltering slavery.

Collision occurred when local improvements, like docks and ports, were bruited and when a Bank of the United States was chartered to regulate and guarantee private banks.

To Anti-Federalist each of these initiatives was unwelcome because each enlarged the federal government. Moreover, taxes on their goods would pay for piers in Boston Harbour and roads in New York state. Meanwhile, the goods the south imported would suffer a heavy tariff. So went the argument in the South.

It was masked as states’ rights. That old sour song still heard today. The champion of this repertoire in Pierce’s time was Andrew Jackson and the Democratic party he created. Though when Old Hickory became president he did not hesitate to use the powers of the Federal government against the states. Go figure.

Meanwhile, with the passing of the Adams dynasty, the Federalists evolved into the Whig Party which advocated the rule of law, a written and unchanging constitution, and protections for minority interests against majority tyranny. It was business friendly. Four presidents served that party, William Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Millard Fillmore.

Generalisations aside, Pierce became a Democrat, swimming against the tide in Federalist and Whig New Hampshire. In this study there is no explanation for this initial affiliation. Car license plates bear the state motto: ‘Live free or die.’

These words graced the New Hampshire colonial flag in the Revolutionary War. It has been the only state where seat belts are not mandatory, and cigarette advertising is not constrained.

Pierce actively opposed local improvements in the Granite State, the state nickname, to stay the dreaded hand of big government, and that led him to a seat in the state legislature where he proved an effective organiser of interests and votes, and companionable fellow. After five years or so he ran for Congress, and the same state legislature elected him and off he went to Washington to curb the dragon in its lair.

His young wife stayed in New Hampshire for her health was and remained fragile. In D.C. he got along with Whigs personally but was a staunch Democrat.

The next step was the Senate and the New Hampshire legislature voted him into one of the state’s seats, and back he went to Washington. However, he stayed only a few months and resigned.

Why?

Multiple causation, perhaps. First, his wife, Jane, refused to go to the swamp of D.C. Second, Pierce had taken the temperance pledge with his father and brothers, and he found it difficult to stay dry in D.C. where he shared a house with four other congressmen who did drink alcohol. To escape the clutches of demon rum, he returned to Concord.

It also seems to this reader that Pierce, after the novelty wore off in D.C., found himself a small fish in a big pond and he did not like that. Back in New Hampshire his was a name with which to be reckoned and so he went back there.

His wife briefly thought he would quit politics and into legal practice, but no. He became chair of the New Hampshire Democratic Party and he ruled that very effectively. He recruited leading lights of towns and villages across the state as members, travelled the state to seek them out, and placed an absolute premium on party unity. No dissent was tolerated. Office holders soon found that an unguarded comment contrary to party policy would see them recalled, unendorsed, banned, and otherwise disciplined. No exceptions. No warnings. No second chances. He was one-man nomeclatura.

Then came the Mexican War. Pierce had no military experience or interest but he knew that he could not sit it out, though he did not rush to volunteer: to be a simple soldier would not be enough for his ego, it seems. After a few months the Granite State governor, acting on a request from Washington D.C. to raise troops, commissioned Pierce a colonel to raise a regiment. He did, and proved himself again an expert organiser.

By the time his ship got to Vera Cruz the war had moved inland and it fell to him to organise the supply line. He did that very well.

However, the three times his command came under hostile fire, he was nowhere to be found… The author gives him the benefit of the doubt (illness, injury, and indisposition) but the men in his command did not. He was widely criticised by the mumblers in the ranks who were all New Hampshire men. But somehow he lived that down by assiduous application to the logistics duty that had fallen to him.

While in Mexico he met many others from across the country whose paths he would cross again later. That service was like a seminar for a future generation of national political and military leaders.

The Whig Party was dividing over the single issue of the day — slavery, masked behind rhetoric of states rights. It had northern and southern wings and within each there were further divisions over the details of the package of measures known collectively as the Compromise of 1850.

The prospects for Democrats were good. In New Hampshire Pierce’s name was bruited as a presidential candidate, but there were others with better, national profiles. Pierce followed the advice of an associate and postured. He had, he said in a published letter, no interest in a higher office that would take him out of New Hampshire….unless he was called to it. It was an obvious signal that he was waiting for the call.

His tactic was to wait and see if the front runners — Lewis Cass, James Buchanan, William Marcy, and Stephen Douglas — would defeat each other and in so doing, exhaust the nominating convention. They did, refusing to compromise among themselves.

After more than forty ballots in Baltimore, Pierce’s name was put forth, and a few ballots later he won the nomination. He became the Democratic candidates in the election of 1852. He was fifth choice.

As was the custom of the day, he did not campaign but remained at home. His supporters did the grunt mostly through the myriad of small town newspapers.

Meanwhile, the Whigs continued their immolation with contending candidates and opposing declarations of intransigence. The incumbent president, Millard Fillmore, a Whig, was denied re-nomination in favour of the Mexican War hero Winfield Scott who was vehemently opposed by southern Whigs as unreliable on slavery. Instead they advocated abstention. Fillmore flirted with the Free Soil Party which favoured opposed the spread of slavery into new states. Scott did nothing …. to court Southern voters. Scott did very little. He had a well deserved reputation for sloth and he lived up to it.

Strangely enough there was a third party candidate, one from New Hampshire, who ran as a Free Soil candidate. Remember those mumblers in the ranks? He got their votes.

Pierce won by a landslide and that was the beginning of the end for the Whig Party, but it left him with a very large party that was anything but united. His Electoral College vote was five times that of Scott, whose political career ended then and there. Congress, too, was replete with Democrats. One of the states where the vote was closest was…New Hampshire.

Super-majorities are invariably undisciplined, and this was never more true that with the huge Democratic majority that assembled in Washington, D.C.

Pierce stuck rigidity to his conception of unity by adherence to the strict letter of the law, even when those letters, having emerged from compromises in Congress, were deliberately vague. In each and every matter, Pierce, after some confused posturing in convoluted messages to Congress, would side with the interpretation of the murky laws taken by the slave-states, perhaps because of his Jeffersonian DNA which rejected any role for the Federal government in nearly anything.

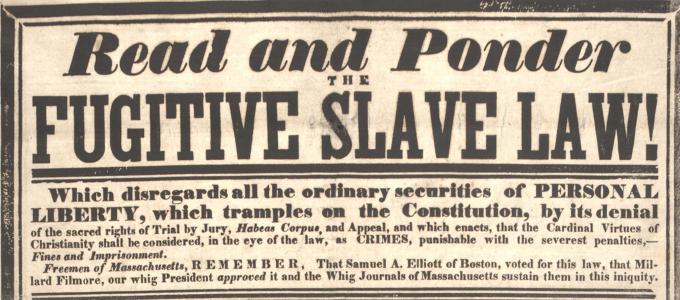

The Compromise of 1850, a set of measures that admitted California to the Union, thereby upsetting the exact balance of the Senate between slave and free states, imposed the Fugitive Slave Act, and proposed local sovereignty on the question of slavery in two future states in Utah and New Mexico (very far in the future). The Fugitive Slave Act made it a Federal crime for any citizen not actively to apprehend a fugitive slave with the presumption that all blacks were slaves. It kindled significant and protests in Maine, Massachusetts, Illinois and elsewhere. In effect northerners were charged to impose slavery.

Then there was Nebraska! At this time the term Nebraska referred to everything west of the Missouri River marking the boundary with Iowa to the Canadian border, and west to Oregon territory. It included everything north of the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. Today that would be Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Kansas.

Land hungry immigrants, perhaps three million of them, were pushing west and railroads wanted to bridge the continent to the legendary riches of California. But the vast tract of Nebraska was lawless and government-less as well as roadless. To sell land to migrants, to license railroads the land had to be surveyed and governed. Hence the pressure to create territories, as the first step to states.

The Unorganised Territory was called Nebraska.

The Unorganised Territory was called Nebraska.

The prospect of more new states threatened further to erode the Southern block in the Senate, and slave interest mobilized. First to stop any development in Nebraska, but that failed because the pressure was too great from migrants at the bottom and railway magnates at the top of the demand curve. The second line of defence of the slave states was to revert to the Missouri Compromise formula of 1820 and admit states two-at-a-time, one slave, one free. This proposal galvanised a reaction from the abolitionists in New England, small in number but mighty in pen. Pierce had a visceral reaction to these agitators.

The result was the Nebraska War in which settlers poured into the area to vote in a plebiscite on slavery. Abolitionist arrived from the north and thousands of Missouri slave holders crossed the river long enough to vote and then leave. Since the easiest access was through St Louis, contending parties often encountered each other along the way and the first skirmishes of the Nebraska War occurred in St Louis.

The South won this war by stacking the electoral rolls with far more voters than did the abolitionists, thanks to the proximity of Missouri, and they voted into office in Kansas, a pro-slavery territory government situated in Lawrence which applied for statehood as a slave state. In many locales the votes for the slavery outnumbered the voters by a multiple of five. The electoral fraud was extensive and blatant enough to make a Florida Republican proud.

The abolitionists, called Free Soil, who wanted to keep all blacks out of Kansas, free or slave (unless they could play football), challenged the legitimacy of this territory government and set up their own rival Free Soil government in Topeka. What a devil’s brew this was! Does this explain why the Interstate Highway to Topeka today has a toll, unlike every other Interstate? (Yes, I have read the official explanation and I know there is a similar instance in Pennsylvania.)

Pierce sided immediately and unequivocally with what he said was the legitimate government in Lawrence and prepared to send in the army to support it. Of course that was the very point at issue, was it the legitimate government? Even some of Pierce’s own cabinet thought it was not, and suggested alternatives, like another closely supervised election.

Pierce viewed that as equivocating, and I suspect also from the tone of his recorded remarks he also took that suggestion as a slight on his person, and rather than admit a mistake, he redoubled his efforts to bolster the Lawrence government. The result was the Jayhawk War between the factions in Kansas which caught in the middle many of those land hungry migrants. In this war the United States Army took the part of the slave-favoring government in Lawrence. This step inked the printing presses of the abolitionists for whom Pierce was the slave master in chief.

Three years into his administration, Pierce was hailed in the south as a true friend of the Constitution, i.e., the slavery enshrined in it, and widely reviled in the north, foremost by the abolitionists, but also by northern mercantile interests who found that in many other smaller ways he favoured the agricultural interests of South over their interests. Western migrants also disliked the use of the army to impose policy. That was too much like back home in Europe.

While Pierce’s public statements were full of patriotic fervour about his love of the United States, specifics were absent. Like so many since and now, he seemed to have disliked most of the reality while declaiming his love for the abstract, ever ready to embrace the flag on the stage, but not a person in the street. It is ever thus.

Further, the Democratic Party was suffering some earthquakes within its ranks, as the subsurface plates of North versus South and East versus West shifted. Ambitious rivals like Stephen Douglas and James Buchanan paraded their wares. While Douglas has been deeply involved in the politicking that led to the impass, Buchanan had been United States ambassador to London and was free of baggage. Douglas was energetic and brash, while Buchanan was discrete and subtle.

Pierce wanted renomination, but soon realised it was impossible. Like Fillmore and Tyler before him, he was cast aside by his party. The nominee was Buchanan, who then won the Presidential election, thanks to the continuing mutually assured destruction of the Whigs.

Pierce repaired to New Hampshire to sulk after the inauguration of his successor, which he handled with some dignity.

Events rolled on, and when the Civil War came he could not resist some ‘I told you so’ public remarks that aroused the censors. To their inquiries he reacted in high dungeon. None of this was a productive turn of events. He made it worse by his belligerence, and, indeed, his remarks, as quoted in these pages sympathise with the South as the wronged party. Additionally, the timing was as bad as possible, because he made these remarks on 4 July 1863 even as news of the great Union victory at Gettysburg was on the telegraph wires. Some suspected he was a Copperhead or at least a Doughface. The former is an active Confederate agent and the latter a trustworthy sympathiser.

His wife continued to live with her sister, suffering from and finally succumbing to tuberculous. The last of the children died in a train derailment when the Mr and Mrs Pierce were travelling to Washington for his inauguration. It was terrible shock to both of them and she never got over it. He seems to have sublimated it.

He turned himself into a farmer and spent some of his time with Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose high opinion of Pierce is the one thing that give me pause, for Hawthorne was an insightful man. How else could he have written ‘The Scarlet Letter’ with a nose for hypocrisy as per ‘The Blithedale Romance.’

Pierce turned ever more to drink and died of liver disease in a few years. Visitors to his farm had often found him in a stupor.

Like so many other presidents, Pierce had no contact with his VIce-President, William King, who was a supporter of Buchanan. In fact, King was sworn in as Vice-President by the American counsel in Havana, where King had gone to seek relief from tuberculous. He died a month after taking the oath. He was a Vice President who never foot in Washington D.C. That left the President Pro Tem of the Senate as next in line for three years and ten months.

The book reads like a synthesis of existing knowledge and not original research. There are no quotations from any personal letters by Pierce. I guess that is inevitable in a series where the emphasis is on complete coverage and not originality.

So what?

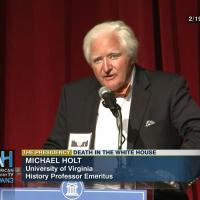

Michael Holt

Michael Holt

The result is quite a distance from the subject because the author has no evident first hand contact with the subject, i.e., he has not held the letters or papers Pierce wrote, nor visited the sites in New Hampshire, nor looked at the local newspapers, but instead harvests from other studies who authors have done that. It is called desk research.

Skip to content