Sometime ago I promised a second instalment from the OSS manual for Allied sympathisers in continental Europe during World War II. For those who have patiently waited, here it is. The manual’s purpose was to show sympathisers how they could obstruct the Nazi war effort by gumming up the works ever so innocently without blatantly risking their lives.

One section was addressed to managers of companies, firms, and organisations from railroads to enamelware factories.

The items read like key performance indicators from McKinsey whose client list has included Enron and Swissair. Remember them?

(1) Demand written orders. Meanwhile, time passes and nothing is done.

(2) Misunderstand orders. Ask endless questions about minute details or engage in long correspondence about such orders. Meanwhile, time passes and nothing is done.

(3) Do everything possible to delay completion. Even though part of an order

may be ready, don’t deliver it until it is completely finished. Say that standards have to be maintained. More time passes.

(4) Do not order new raw materials until current stores have been exhausted, so that the slightest delay in filling your order will mean a shutdown. Why? It is inefficient to hold surplus material. Time keeps passing.

(5) Order only high-quality materials which are hard to get. Warn that inferior materials will mean inferior products. There is never enough high-quality material to go around so this order leads to an argument about priorities. These arguments never end. More time passes.

(6) In making work assignments, always assign the unimportant jobs first. See that the important jobs are assigned to inept workers. This is definitely from the McKinsey training course.

(7) Insist on perfect work in relatively unimportant products; send back for revision those products which have the least flaw. Approve other defective parts whose flaws are not going to be detected until use in the hope these products will fail at a crucial moment. Thus one appears fastidious but lets slipshod products through. Another chapter in the training manual, that one.

(8) Make mistakes in routing so that products are sent to the wrong place. A few well chosen typographical errors do the trick. If the reports have not been acknowledged, then one cannot proceed.

(9) When training new workers, assign training to those who have have no experience in the hope that they will give incomplete or misleading instructions. Ah, a favourite of mine. McKinsey all the way. The trainers have never used and never will use the system that they train others to use. A classic.

(10) To lower morale and with it, production, be pleasant to inefficient workers; give them undeserved promotions. Discriminate against efficient workers; complain unjustly about their work. Reward the incompetent and punish the competent. This one has long a key performance indicator for some modern major managers.

(11) Hold meetings when there is more critical work to be done. Do so especially when the pressure is on, declaring that only by discussion can morale be raised.

(12) Multiply paper work in plausible ways. Start duplicate files offsite. Who can object to paperwork? Preparing, sorting, and filing takes time. Assign one of the best workers to this clerical job on the grounds that the paper trail must be perfect.

(13) Multiply the procedures and clearances. See that three people have to approve everything where one would do. Make sure it is always an odd number in the hope that there will be disagreement among them. Invoke our old friend standards again.

(14) Apply all regulations to the last letter. Work to the rule. Was for orders; show no initiative. The more obscure and less relevant the regulation the better. See standards above.

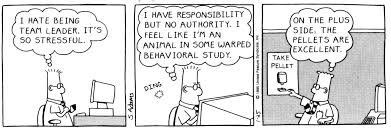

I never got the pellets.

I never got the pellets.

The OSS was the Office for Strategic Services, the forerunner to the CIA.

Skip to content