This book is a popular presentation of some serious studies in the psychology of perception and memory. It shows how counter-intuitive reality can be. It also overstates its case and enforces a technical vocabulary where it adds little or nothing to the general reader, who seems to be the target audience.

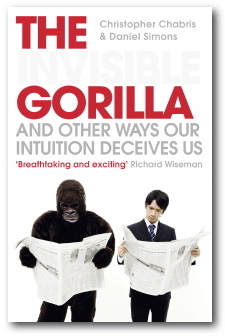

The video that made the authors famous and which explains the title can be found on You Tube. It is a psychology experiment in which observers are instructed to count the number passes a basketball team makes, and while the observers count, a gorilla walks across the court. Well, a student wearing a full-body gorilla suit, since the research grant did not run to capturing and training a complaint gorilla.

Imposible to miss!

Hmm, missed by about 50% of all subjects through repeated iterations and variations.

We can indeed miss things in front of our very eyes, and do so nearly every day. So I say from personal experience. Because we miss them, we suppose they were not there, but they were.

The explanations are many, and in these pages become increasingly, and needlessly, complex, no doubt to justify the grants that produced the fame and book contract(s). My cynicism is showing.

We see most readily what we are looking for. Indeed we often can only see something if we are looking for it, and in concentrating on that, we miss much else. Whoops! But then concentration is supposed to do that, focus.

In parallel we are less likely to see what we are not looking for, and the even less likely to see it, the more out of place it is. This latter is counter-intuitive. But that gorilla is an example. It is completely out of place and, consequently, invisible (to half the watchers). Another player, a coach, a referee, a cheerleader wandering onto the floor might have been spotted more often for the fit the context.

To reiterate. something extremely odd can be the most easily missed. See, counter-intuitive, because one would think the oddest things would stand out, but they do not always do so. Sometimes, yes, but often times no.

Add to this perception blur-memory and the plots thickens. If it is not perceived in the first place but is just a blur, memory cements over it, and it never happened.

The authors demonstrate these failings, which seem very plausible in my own personal experience, with a combination of laboratory experiments and case records of automobile accidents, flight simulator video evidence (nearly enough to put me off flying), conflicting eye witness testimony, and trial records. The range and variety of this empirical evidence is impressive.

One of the governing points is that our contextual expectations shape perception and also memory. We do not expect to see a gorilla while a basketball team practices passes.

There is also cognitive load, which the authors do not give any attention, but they do note that when the task assigned to observers is made more difficult, gorillas sightings decrease. For example, to ask observers to count separately air versus floor passes makes the gorilla all but invisible to everyone. The more complex the assignment, the more concentration it takes, the less attention remains to detect the unexpected.

There is another example of cognitive overload in these pages. Drivers who follow the GPS oral directions despite the obvious mistake it is making. They ignore flashing lights, barriers across the road, and drive off collapsed bridges, over the culverts of incomplete roads, and on to rail way tracks because the computer voice told them to do so. I would like to think I would not do this, but…. I have found GPS directions mistaken when roadworks blocked the recommended routes and had the wit to stop on those occasions. Who knows what the future will bring?

Of course, magicians and other illusionists have long exploited misdirection, distractions, sleights of hand, and lighting to make audiences see what the magician wants its members to see and not what is in fact happening before their very eyes. The authors have not yet referred to this domain in my incomplete progress through this book. Though the illusionists do not publish in ranked journals and apply for National Science Foundation grants, hide behind polysyllabic jargon, nor make mountains out of molehills as scholars must, so they may get short shrift in these pages.

There are many more ingenious experiments to justify research grants. If magicians are neglected so too is the simple fact of concentration. If I am concentrating on counting passes maybe I should not see the gorilla. Perhaps the observers who see the gorilla made mistakes about the pass count. Nothing is said about the accuracy of the observations, but if I were paying pass-counters that is what I would want them to do, count, not notice gorillas. Many of the examples given involve witnesses who are not concentrating. A student passes people on the street, and one says ‘Hello.’ Five minutes later the student cannot describe this person. Well, so what? If that student had been told the description would be on the final exam, it would have been remembered.

Two passengers in a moving car see an assailant pull a bike rider to the ground. Interviewed by police thirty minutes later and they give different description of the assailant. Again, so what? They were not concentrating on the scene. It was a blur.

Of course, the authors’ point, is in part, that such witnesses each individually think they do have an accurate description even when one, if not both, of them must be wrong. It is this confidence that is the underlying problem, and the authors nail that. It is the this also confidence that presents many problems. Agreed, but I am not sure this book has narrowed that down any.

Though in doing so, it seems like overkill. The messages seems to be that no one is ever right in the first place and subsequent memory further erodes. To give up would seem to be the best response to such a hopeless situation.

I thought of these two when reading about memory in this book.

I thought of these two when reading about memory in this book.

Hmm, well I just watched an American football game and there the players with enormous concentration remembering intricate plays from a manual of fifty or more, in a deafening stadium, driving rain, with hard hitting opponents, carrying injuries, and growing tired toward the end of the season and the end of the game. Memory does work better when one concentrates.

The authors offer some amusing anecdotes to illustrate the fragility of memory but to this reader that is all they are: anecdotes. Men often appropriate each other’s stories as their own in the retelling and when challenged about it, get very defensive. (I have even seen women do this.) What is going on in such cases is not primarily a false memory but a stupid lie followed by a masculine refusal to admit it. No National Science Foundation grant is required to explain this everyday event.

More disturbing are airline pilots in simulators who are so absorbed in reading gauges that they do not notice the tanker-truck on the runway.

A tendency in this book is to name a ….a what? … a syndrome, and then move on to another ingenious experiment. The missed gorilla and the missed tanker truck are treated as instances of the same tendency and yet they differ so much in context and consequence as to be different in kind.

Moreover, to this lay reader (I thought about say layman to see if it would arose a comment about gender but I forgot) that the nominalism is not very informative. By nominalism, I mean naming a pattern of (mis)perception – e.g, inattention to change, and suppose we now understand how it works. We do not; what we have, often in these pages, is a description with a label.

Charles Chabris

Charles Chabris

Daniel Simon

Daniel Simon

While I am airing my nits, I find the book replete with name dropping of colleagues and of universities. Perhaps some editor encouraged that to make it more personal and less austere and scientific for a general reader but it makes it read too much like a letter to mom identifying all of the fraternity brothers and sorority sisters. It is all of a piece with the me-ism of the selfie.

Warning! cynicism overload.

Skip to content