Chester A. Arthur (1829-1886) was 21st President of the United States (1881-1885).

Chet was born in Vermont and went west briefly to make his fortune before settling in New York City. He is often associated with the worst presidents in rankings by historians, along with Warren Harding, Franklin Pierce, Ulysses Grant, Millard Fillmore, and Andrew Johnson. Yet he is the president who signed the Pendleton Act into law, one of the landmarks of 19th Century politics.

His religious father was a devoted abolitionist and Chester, at his urgings, went west to practice law and to keep Kansas a free state. He found the wild west very wild and very far away and stayed only a few weeks before heading back. That was the first, and perhaps the last time, conviction governed his actions.

He made his way in New York by attaching himself as a loyal lieutenant to movers and shakers. He was personally sociable and gregarious, a man who positively enjoyed wiling the night away in men’s clubs where he got to know everyone and offended no one. While he was never anyone’s first choice for anything, no one was ever against him, ergo a reliable second choice at any time.

When the Civil War occurred he duly took to the colours of the New York state militia where he was appointed a quartermaster general by a patron. He secured this plum and cushy appointment, a long way from the cannon’s roar when hapless migrants were conscripted to die in the fields of Virginia, by the grace and favour of one Roscoe Conkling, who at the time and place was a kingmaker.

At the end of his military service, Arthur was a rich man. Our author has it that his law firm made a lot of money. Class, see if this makes sense: As quartermaster general he let contracts worth millions for food, weapons, clothing, boots, animals, fodder, leather goods, and more. Ever heard the word ‘kickback?’ Our author has not. Wikipedia is more suspicious and implies that Arthur used his position as quartermaster general in the most populous state to enrich himself.

He was not especially avaricious about it, but then he was not subtle either. Why bother when it was common practice to do so. Think Tammany Hall, and there is the picture, an alliance of Democrats and Republicans to exploit the government. Has a modern ring to it, doesn’t it?

Moreover this client passed even more ill gotten gains on to his patron, Senator Conkling, who was sometimes referred to as ‘His Lordship.’ Lord Conkling was avaricious and wanted all he could get, in part to bank roll his own plans for the presidency.

Arthur enjoyed luxury in food, furnishing, alcohol, and cigars which he generously shared with cronies in his Fifth Avenue hotel suite, which he kept even after marrying. Indeed the only point of tension with his wife was his persistent networking and socialising at the hotel night after night. She, Nell, died unexpectedly and young and left him a widower who continued the same life.

Conkling had him appointed Collector of the Port of New York by President Rutherford Hayes in a spoils deal. In return for supporting Hayes’s election campaign in New York state, Conkling got to allocate federal government position in the state. It was routine at the time for each new president to dismiss the entire workforce of the federal government and appoint anew those who had supported him, a changeover that might take a year to complete. Call these office seekers. This is the spoils system which had reached its peak by this time.

The Collector of the Port of New York was one of the most important positions in the country. Far more important than most cabinet offices or governor’s chairs. What was collected was tariffs on imports and taxes on exports, and the resulting revenue in New York consisted of more than half of the income of the federal government.

By some quirk of circumstance unknown to our author, Arthur and Conkling became ever richer during his tenure as Collector. Class, figure it out. Whatever, the brandy was French, the cigars were Cuban, the sofas were stuffed, the food was rich, and Chester Arthur moved in the world of J. P. Morgan, Jay Cooke, John Jacob Astor, John Rockefeller, Daniel Drew, Jay Gould, Charles Crocker, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Robert Risk, and other Robber Barons who ran the country while Hayes played at being president. Arthur moved in that world but he was not of it, a hanger on, not a scion.

There is silence about women.

Arthur was much whiskered, carefully coiffured, a dandy with expensive clothes and accoutrements. He liked all of these trappings of wealth, perhaps because they compensated for his lack of good looks, commanding presence, or manly experience in the Civil War or on the frontier. Reading of him I was reminded of a passage from ‘The Great Gatsby.’ Applied to Arthur it would mean he knew himself from the outside in. He wore expensive clothes so that meant he was an important man, and so on.

Arthur was one of the first customers for a new fangled designer who worked with metal and glass, named Charles, Charles Tiffany, who later became famous for his lamps.

After the Civil War the Republican Party, wrapped in Abraham Lincoln’s bloody shirt, was the dominant political force. The Democrats condemned for their association with rebellious southern states dominated a few cities in the north but otherwise were a spent force for decades. In the broad church of the Republican Party there were deep rivalries based on personalities, not ideologies or regions.

The most important one was between the ambitions of Roscoe Conkling and James Blaine of Maine for the presidency. These two were alike in their ideology-free ambition and unalike in every other way. Conkling was a bon vivant, open schemer, sybarite, aggressive, crude, and ill mannered. He fits the 7MATE demographic, a real man’s man.

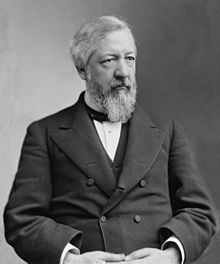

Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling

Blaine was withdrawn, introspective, perhaps shy, and reflective, more inclined to read Caesar’s ‘Gallic Wars’ than to drink with the boys. More the SBS2 demographic. Their respective factions divided the Republican Party in half.

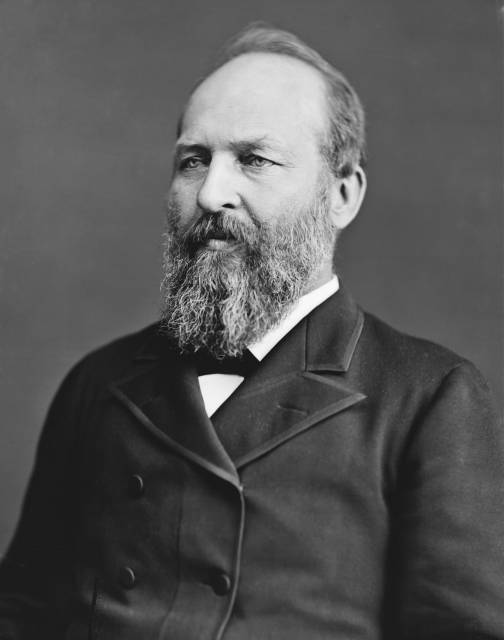

James Blaine

James Blaine

After a succession of Republican presidents, Grant, Hayes, and then Garfield, all Union generals, and the end of the military occupation of the South in the so-called Reconstruction when the seceding states laboured to pay taxes to settle the war debt, the Democrats came back to life. Off and on there was talk of a third term for Grant, which was new to me.

Conkling and Blaine both wanted the Republican presidential nomination in 1880, but more than that, each wanted to be sure the other did not get it. They undercut each other so effectively that James Garfield, who was not a member of either camp got the nomination. To win, he had to make peace with the two godfathers of the party and this he did by promising Blaine the office of Secretary of State and the say in a number of other appointments, which Blaine supposed he could use to plan a later push for the highest office, and by promising Conkling complete sway in New York state. The rivalry had become personal to Conkling and he would not serve in a cabinet that included Blaine he made clear, and New York was good but not enough.

Garfield pondered Conkling’s intransigence and then went directly to Arthur and offered him the Vice Presidential nomination in a move replicated nearly a hundred years later when Jack Kennedy went directly to Lyndon Johnson, no intermediaries, no consultation with trusted advisors. Arthur immediately accepted and shook hands with Garfield.

Conkling was outraged. Which was the greater felony? That Garfield went straight to Arthur without first asking Conkling if he could approach Arthur, or that Arthur accepted without seeking the approval of Conkling. The journalists observing all of this, often in the same room when the deals were done, supposed Arthur would not withstand the inevitable brow-beating from Conkling, and were thus surprised when he later appeared on the podium.

By the way Conkling was nicknamed ‘Lord Conkling’ and he liked that. He liked having graft monies delivered to him while sitting at his desk in the Senate like a lord receiving tribute from vassals

For the first time in his life as an ever loyal second Arthur defied his boss and told him so to his face. Conkling was apoplectic but when he calmed down later, he made the best of if because at least Blaine did not get the nomination and reluctantly allowed his New York state machine to campaign for the Garfield-Arthur ticket.

James Garfield

James Garfield

Garfield won and Arthur was installed as Veep, where his major duty, like all before and after him was to preside over the United States Senate’s meetings. This purely nominal duty turned out to be more important than any of the pundits expected for the Senate was evenly divided between Republicans, who had spent a lot of time fighting among themselves, and resurgent Democrats at thirty-seven each. Arthur had the deciding vote and he suddenly became an important person, not just a figure head.

Conkling’s influence nosedived from that day on. In fact, he soon lost his own Senate seat, so gross were his malefactions that even the New York legislators could not overlook them, and he was turfed. now a footnote of history.

Garfield took the oath of office and Blaine became Secretary of State. Three months after that Blaine walked with Garfield to Union Station to take the train to New York City when Charles Guiteau shot Garfield in the back. Two police officer grabbed Guiteau who made no effort to escape. Instead he told the officers that he had shot Garfield so that Arthur could be president, a line he stuck in his subsequent trial. Huh?

Arthur had nothing to do with any of this, that is absolutely sure, but Guiteau said it and more than once. Guiteau was a distant follower of the Blaine camp and he had formed a hatred of Conkling and his influence and he erroneously perceived Garfield to be Conkling’s catspaw. At his trial the defence attorneys argued that Guiteau was insane and that made about as much sense as Guiteau did.

When I learned of Garfield’s murder as a school boy the line was that Guiteau was a disappointed office seeker who took revenge on Garfield for not appointing him to a lucrative federal government office, and this line is still followed in the Wikipedia entry. There is truth in that interpretation because he had written letters asking to be appointed, but it is not what he said.

Arthur was in New York City when the telegram arrived telling him Garfield was wounded. A few minutes later a journalist arrived to tell him what Guiteau had said about him – Arthur. Gulp! ‘What to do?’ he must have thought. He went immediately to Washington to see Garfield, who was comatose and to see Garfield’s wife and family and offer sympathy and aid. He then retuned to New York City and stayed there Incommunicado for the three months that followed while Garfield slowly died.

His reasoning was that he best not appear eager for the office, and indeed, it seems he was not, and so he kept the lowest possible profile.

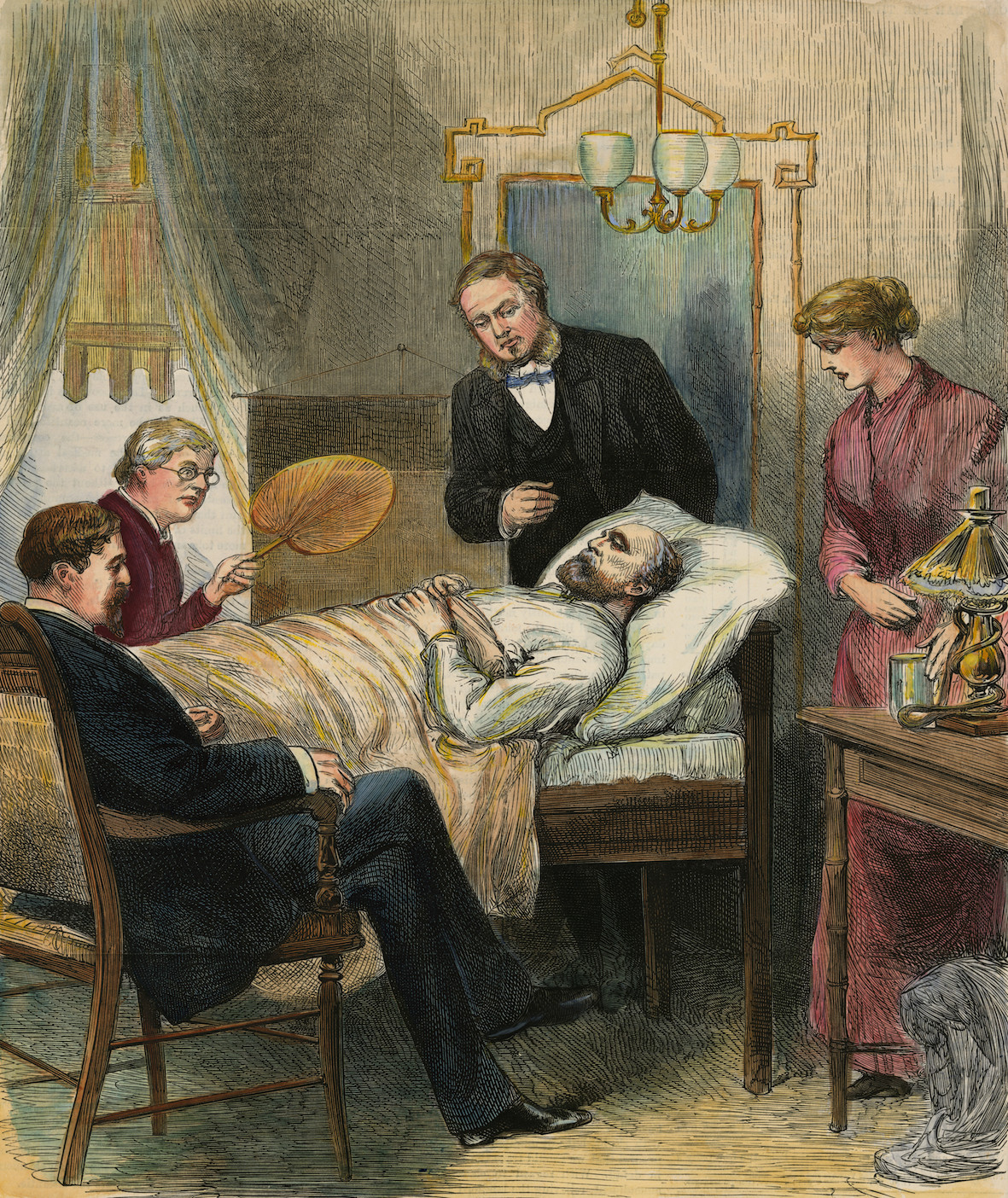

Garfield, wounded.

Garfield, wounded.

Another telegram arrived to announce that Garfield was dead. A local judge administered the oath of office and he was the twenty-first man to be president of the United States on 22 September 1881.

Guiteau argued his own defence, and his blame-shifting reminded me of some people I have worked with. First that Guiteau shot him is Garfield’s fault for walking to the station and so exposing himself to attack, that Garfield died of the wound is the fault of the incompetent doctors who did not save him, and that he died in New Jersey and so a D.C. federal court could not try him. Marvellous, but he was hung.

Arthur returned to Washington and took a hotel suite, leaving the Garfield family in the White House as long as they wanted.

As discrete as he was and considerate of the Garfield family, his incommunicado also meant there was no executive in the government for three months. This is a time when there was constant friction along the vaguely demarcated Canadian border, when European powers flirted with interventions in Mexico and Guatemala while the Indian wars were continuous and anti-immigrant riots were frequent in New York City and San Francisco. Though our author is silent on this I rather think James Blaine may have steadied the ship.

Arthur took the oath of office in Washington and made a short but apt speech some of which is quoted in this book as his ‘inaugural address.’ I balked at that word ‘inaugural’ because succeeding vice-president were not elected to the office of president and so do not give inaugural addresses.

No sooner had Arthur sat down in the big chair than all his drinking buddies, led by Roscoe Conkling, arrived, sat down, and put their feet up his desk, and called him Chet.

This worm turned. Arthur firmly directed them to remove their feet from the president’s desk and henceforth to address him as Mr President. Conkling choked on this rebuke but swallowed it. The others did as they were told. Conkling had expected to secure a cabinet appointment and he also expected to see Blaine dismissed. Neither happened.

At this point Arthur had one outstanding quality. He owned no one anything. No one had expected him ever to be president and so beforehand no one had bothered to extract commitments from him and his incommunicado had prevented later efforts at that. He was his own man. On the other hand, there was nothing he wanted to do, nor was he committed publicly to do anything. He stuck to that with one exception. In all of this there are many parallels with John Tyler who became tenth president.

Installed in the White House Arthur made his sister the hostess, and she set about redecorating the dump, encouraged by Arthur. Louis Tiffany came to the fore and made his reputation there. Virtually nothing had been spent on the White House since it had been rebuilt after the War of 1812. Congress repeatedly refused to fund anything for the president. Before it could be redecorated, much of it had to be rebuilt from the inside out and it was. In the aftermath of Garfield’s death Congress voted this presidential expenditure. The changes wrought as described in these pages sound grand, but all them were ripped out by subsequent occupants to keep up with the fashions of changing times and nothing is left of the Tiffany White House. It all went into the landfill.

An example of a Tiffany screen like one installed in the White House.

An example of a Tiffany screen like one installed in the White House.

The Robber Barons continued to rob. The army continued to murder Indians. Attacks on Irish immigrants on the East Coast and Chinese on the west were a daily occurrence. British and French interests continued to plot in Central and South America. More than once, shipping on the Great Lakes was interrupted by British patrols.

The federal government had grown during the Civil War and since then business had boomed. The coffers were full and the size of government began to diminish. Arthur ran a surplus and cut excise taxes.

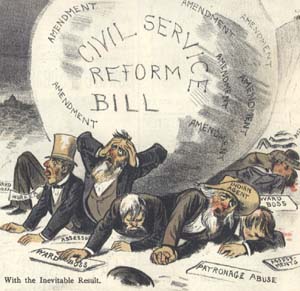

The spoils system, started by Democrat Andrew Jackson, had become a monster that consumed itself in the case of Garfield’s murder for the label disappointed office seeker stuck to Guiteau ever after, and the longstanding minority voices calling for a reform of the civil service were reinvigorated and now heard afresh. The example of the 1854 Northcote–Trevelyan Reforms in Great Britain the generation before was cited and speakers spread the word as did newspapers. The result became the Pendleton Act of 1883 which Arthur, a creature of the spoils system, signed into law, ending the very system that had made him. Ironies of ironies.

It slowly established civil service examinations for entry, seniority for promotions, ended levies of political contributions from salaries, and myriad of other things. Democrat George Pendleton of Ohio sponsored the legislation in the Senate. When its centenary came in 1983, I was sorry to see it pass pretty much in silence.

The Republicans had long been complacent of their domination of federal politics, but a rude awakening was delivered in the mid-term Congressional elections in November 1882 with Democrats sweeping into majorities in both houses. As a last ditch effort to redeem itself in the eyes of a jaded electorate the old Republicans who still dominated Congress passed the Pendleton Act, which had been languishing in committee for years, to claim the mantle of reform before the new members of Congress were invested in March 1883 and preparations began for the November 1884 presidential election.

One effect of the Pendleton Act was to drive political parties into the arms of business and later trade unions to seek money to campaign the length and breadth of the land. The toxic embrace endures today.

The immediate effect was to undercut Arthur’s support in New York which was entirely based on patronage. The Pendleton Act pleased no one. For the reformers it was not enough and for the spoilsmen is was too much. Thus Arthur alienated his allies and did not win any new friends to replace them. At last Blaine got the nomination for 1884.

Arthur’s high living had also caught up with him in a combination of internal ailments which left him weakened. He died shortly after leaving office at fifty-seven.

Zachary Karabell

Zachary Karabell

This was an easy book to read and it is sprinkled with insights and some very well turned phrases. It is odd that the author seems deliberately to turn away from the obvious fact that Arthur systematically used public office for his own private enrichment. Yes, others, too, did so but they were not president and he was and they are not the subject of this book and he is. It is also disconcerting to see several references to Thomas Reeves, ‘Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester A. Arthur’ (New York City: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975) as the authoritative biography. It made me think I should have been reading that. As is the case with books in this series, this one is not based on primary research but rather synthesises existing biographies, and so it remains at a distance from the subject and a reader feels that.

Skip to content