Ed Murrow (1908-1965) did much to create, found, and shape broadcast news on radio and later television for two generations. His imitators have been many but none had the gravity and grace of the original.

Son of a lumberjack in Washington, Murrow worked his way through college as a sawmill hand. He became active in student politics with the quiet fervour of his Quaker upbringing in the belief that the educated must serve the community and each individual must strive to leave the world slightly better.

He was tall at 6 feet 2 inches and in college developed a command of the language and a speaking voice that compelled attention. His major was speech and his teacher was a gnarled and crippled woman who was nearly a dwarf. He saw the light in her demanding eyes and she saw the future in this gangly youth. Even at the height of his fame she wrote to him with critiques of his work which he integrated into his approach.

Why dwell on his college speech teacher here at the outset? Because many years later when Murrow was instrumental in the final downfall of Senator Joseph McCarthy, the junior senator from Wisconsin, that specimen would imply an unholy union between the boy Murrow and this teacher. McCarthy was a twit but at least he did not tweet.

Murrow became student president and represented his college, Washington State at Pullman, at meetings of such student leaders. Though personally shy and diffident, at the podium he made a mark, and soon became national president.

He organised a national meeting of students in Atlanta and went to great lengths with some sleight of hand to ensure it was colourblind. There was resistance but he had thought it through and had adequate counter-measures, one of which was the press and publicity.

Radio was new and to fill up the air, a program was offered to the National Association of College Students, and its president, Murrow, began his broadcasting career. He filled the space by asking leaders to use the hour to address the youth of the nation, like Albert Einstein, like the Soviet ambassador, like Joseph Kennedy, like John Dos Pasos…. Murrow was twenty-one at the time. Some preferred question and answer and so he began to interview them.

When he graduated he went to work for the International Institute of Education in New York City in what was in effect an unpaid internship that offered room and board. This Institute ran student exchange programs between the United States and Europe. He proved invaluable and money was found to pay him.

As the field representative of the Institute he travelled the United States promoting international exchange, and to Europe to recruit students and see the conditions for American students.

So what? In Germany he saw Adolf Hitler speak in 1931. While he understood little German, he felt the rage, the palpable hatred, and the spewed malevolence and was repelled.

When Hitler became a force Murrow tried to exclude German students who were Nazis coming to the United States on exchange. When the purges of German universities began, the Institute became a fundraiser and placement bureau for intellectuals, like Thomas Mann, Herbert Marcuse, Hannah Arendt, Paul Tillich, Reinhold Niebuhr, and more than three hundred others. Better than nothing but there were 6,000 others. He was a callow twenty-five.

He solicited funds from the large foundations like Ford, Sage, and Rockefeller to support the intellectuals and then convinced universities to take them with their salaries paid by the foundations. Harvard refused, but most others were only too glad to have the free gift of their services.

Thereafter the volume and pace of the work he did re-doubled never to abate until the cigarettes killed him.

He reported the Battle of Britain from London rooftops, inspiring the bold souls among subsequent generations of journalists to imitation. Some called him the poet of pain for his vivid descriptions of death and destruction for the radio audience in the States. All stated calmly and clearly as the rain of bombs drew ever nearer. He endured the Blitz along with Londoners from whom he took his signature phrase ‘Good night, and good luck.’ The ‘good luck’ referred to surviving the night’s bombs.

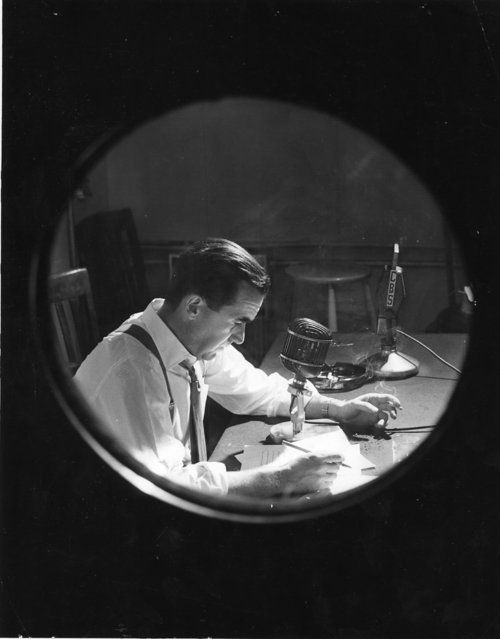

At work in a BBC studio.

At work in a BBC studio.

A few of his rooftop broadcasts can be found on You Tube.

He flew as an observer on twenty-five RAF combat missions on some of which the plane was shot up and crewmen wounded and killed, yet he was disturbed, and said so, by the policy of city bombing.

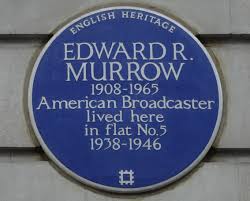

A plaque in London.

A plaque in London.

He stood and watched as U.S. Army Rangers shot the padlocks off a gate of a death camp at Bergen-Belsen and with the medics walked through it in stunned silence. He knew of the Holocaust and had spoken of it on the air but seeing is ……. [unspeakable]. He did later do a broadcast about Buchenwald.

In the 1950s he forced CBS Television to line up against the egregious Senator McCarthy while ‘I Love Lucy’ dominated the other networks. Having once refused Hoover J. Edgar’s demand for airtime, Murrow went on the FBI’s long Enemies List and an FBI file was generated out of mist: Murrow was friend to Harold Laski, had interviewed Earl Browder when he was on the presidential ballot in thirty-nine states, employed journalists who had once gone to communist talks, the college speech teacher was a second-generation Russian, refused censorship about lynchings, spoke at civil rights rallies, hired women to broadcast and not to answer the telephone, had been to Moscow, emphasised the Soviet war effort, and other thought-crimes.

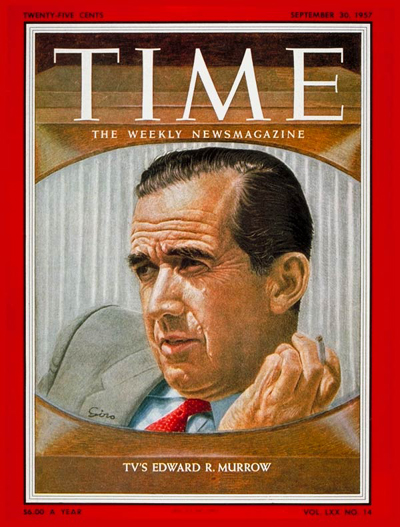

August 1957

August 1957

Murrow reciprocated, and opened a file on Hoover J. Edgar and the FBI. He turned loose his own investigators to compile an exposé on the corruption, nepotism, and incompetence of both. It was never made or aired but the file existed and was known to exist. (See Fred Cook, ‘The FBI Nobody Knows’ [1964].) FBI innuendo campaign abated.

While the sunshine patriots like several recent Presidents of the United States remained Stateside, Murrow went to South Korea and walked on one night patrol. Back in D.C. Hoover and his puppet in the Senate continued to denounce him, the more so when Murrow interviewed black GI’s and compared their service in Korea to the racism at home.

Frontline interviews in Korea.

Frontline interviews in Korea.

As executive producer at CBS Television Murrow had complete control of ‘See It Now,‘ a weekly current affairs program at prime time, and he dedicated one episode to demolishing the Junior Senator from Wisconsin. Whoa! CBS management ran a mile to disown it with a display of corporate cowardice familiar to anyone who has worked in a large organisation full of self-proclaimed leaders who disappear at the first rumble, leaving Murrow and his team out in the cold. Most of them, including Murrow thought it was a suicide note. This episode can be found on You Tube.

In the swirl that followed President Dwight Eisenhower said in a press conference that Murrow was a personal friend whom he admired. This was the beginning of the end for the Wisconsin midget.

In 1961 Murrow sat in President John Kennedy’s cabinet as Director of the United States Information Agency. Senate confirmation was vexed but successful. Quoting Rudyard Kipling, Murrow said, he reported things as they were, good and bad. News, not propaganda. That riled many a senator but they stayed their nays. Why such restraint is not specified. The first test was The Bay of Pigs and Murrow lived up to his motto.

He respected President John Kennedy but distrusted Robert Kennedy for his past affiliation with McCarthy. In both cases the feelings were reciprocated.

These are the high points; the details are many. He interviewed Fidel Castro with sympathy but later reported the barbarity of the Castro regime in murdering its defeated foes and their families through show trials, thus Murrow alienated both the regime’s enemies and its apologists.

When CBS management claimed sponsors did not want to support his critical programs, he went directly to the sponsors to explain and justify his subjects, wInning the life long friendship of some like the president of ALCOA who thereafter stood by him when the CBS management did not. So many leaders and so little leadership as on most larger organisations.

Well into the 1970s CBS News still basked in the reputation Murrow had created for it. In those days news and public affairs dominated the prime time programming of CBS. Fearless and factual in deed as well as in word. Against that standard the cartoons of Fox News are trivial, trite, and tiresome.

The cigarettes — sixty a day — killed him. In 1963 he had major surgery, but he ‘had absolutely no hope,’ as he said, and was largely incapacitated thereafter. The book closes with the funeral without any summing up. Too bad, because some effort to conclude would have been welcome. What was the major formative experience in his life? What was his legacy in the profession? Will we see his like again?

Ever the realist, Murrow expected the worst from the development of the mass media, and often said so. Those fears are now reality. Fact and fiction have blended in an opinion soup made by the hot air of rumour. Entertainment dominates all. Think of those people who say they know an historical event or person because they ‘have seen the movie.’ Dr Goebbels wins again. Journalists will happily assert there is no truth. Another win for Goebbels.

It is a large book only available in print, not Kindle, and only second-hand, running to eight hundred pages. His life and times are fascinating and the prose is clean and clear just like Murrow himself, as they used to say in the newsroom, ‘a straight lead.’

I could not find a photograph of the author. But Sperber has at least one other title on Amazon.

Skip to content