Henry Ford decided to produce the rubber for Ford vehicles. East Indian rubber from Ceylon and Malaya was too expensive and controlled by Britain. Much of that rubber had come from trees seeded from Brazil a hundred years before. Ergo Ford turned to Brazil, while he also invested heavily in Thomas Alva Edison’s research to synthesise rubber in the United States.

This novel is set in the deep Amazon jungle where the Ford company created a vast rubber plantation. It is told from the perspective of a new employee whose job it is to recruit labor for the colossal work of producing a quarter of the world’s supply of rubber. He is an Argentine, neither European, American, nor Brazilian, and so at a distance.

His journey upriver through the morning mists, the afternoon miasmas, and the ominous nights reminded this reader of Captain Willard’s trip to find his Mr Kurtz. (You either get it or you don’t, Mortimer.)

The enormity and eternity of the Amazon are described along with the many locals whom our protagonist meets as he seeks employees. Against the relentless pressure of the jungle, the efforts of the Ford officials decay from idealism to pragmatism to despotism. Their mission to bring civilisation to the jungle reduces them to lesser men.

There is woman from the Ford Company’s sociology department researching the project and she provides our hero with a love interest in a small aside.

The tension in the novel is encapsulated early by one of the local Ford executives who said, ‘we work twelve hours a day to civilise the land and the jungle works twenty-four hours a day against us.’ It wins in the end.

The rubber trees flourish in the jungle in part because they are at distance from one another, whereas in the plantation they are closer together. When a fungus assails one tree in the planation it passes to the others in a flash. In a day a thousand treees have it. Over night ten thousand. Worse the diseased trees attract pests from the jungles that speeds the rot and carry diseases that effect humans. The only treatment if to burn the infected trees.

The fungus does not exist in the East Indies, so says the botanical expert brought in to consult far too late in the piece. That is why Brazilian trees taken there a century before have prospered.

To admit defeat would be to admit that Ford might, ingenuity, machines, money, and enlightenment science cannot tame nature. It also spells the end of several careers.

Before the crisis there is some travelogue up and down the river where many different types are encountered.

Interspersed with the Amazon chapters are some from Detroit featuring Henry Ford. I found those interesting enough to consider finding a biography of him. In these pages he is reasonable, patient, and more willing to face reality than his subordinates. He is also obstinate and treats his only son Edsel like a puppet, and a hypocrite, yet he shows avuncular patience with a worker on the assembly line at Rogue River. His anti-semitism is iterated but mechanically.

Despite the glowing reports from the executives in Brazil, Ford reads between the lines of the reports and visits the place himself. It takes him a few hours to realise that the jungle has won and the best thing is to declare victory and leave. To hide the defeat he buys off the parties involved, rather than punishing them and admitting the failure.

The period seems to be between the middle of 1929 and say 1932 or 1933 to judge by the passing references to world events.

The novel is easy to read with a well judged combination of description, dialogue, and some action. The cross cutting between the corporate jungle of Detroit and the wilds of the Amazon are in proportion, though it is a technique that I do not like.

While it is clear the author found the whole idea of the plantation repellant, the book lets the events and characters act it out, leaving the reader to draw conclusions. There are no sermons nor are there any one-dimensional characters. The author is an historian and this is his first novel. Whether there is second I do not know.

Eduardo Sguilia

Eduardo Sguilia

There were a couple times when I thought the translation clanged; don’t know why, but it did not sound quite right.

I also have a book about Fordlandia by a historian to read. Since it was published later I read the novel first.

Month: April 2017

Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City (2009) by Greg Grandin

A wide-ranging and informative account of Fordlandia by an historian. There is much about Ford the man and Ford the company at the outset that was new to me but not altogether necessary to the story of Fordlandia, leaving me with the feeling that everything the author found was forced into the book relevant or not. For a book about the Jungle City more than half of it is about Dearborn Michigan.

That Ford came to replicate Dearborn in the Amazon may be true but we did not need quite so much background for that point to be made.

Ford’s proselytising efforts to mould new industrial men, my phrase, in his workforce is interesting. Like other paternalistic employers, Ford thought that if he paid well and supported clean living, the men will be responsible employees and that is that. Fordlandia became a laboratory test of that proposition on a green fields site far away from the temptations of Detroit.

The size of Ford’s industrial empire was enormous in the 1920s. Seventy-five thousand employees in Michigan and a like number elsewhere.

Ford had long believed in vertical integration. Growing its own rubber fit with that approach.

Settling on the Amazon was fraught for many reasons. There was much corruption in doing the deal, though Ford did not know it. There was much incompetence in the management and constant blame shifty and backbiting among the managers. Ford did know some of that.

To compress a longer story. None of the managers sent there knew anything about the tropics, the local people, or rubber trees.

Instead they were enjoined to replicate Dearborn there. To wit the buildings were planned in Dearborn for Michigan conditions and built there. These building were all wrong for the climate and terrain but it had to be that way for the press photographs.

When the rubber market changed, Ford pressed on in part simply to show that with enough effort it could be done. Climate, jungle, tropical pests, Brazilians, they would all yield to the genius of science, engineering, rationality, and logic. And money.

The original contract that ceded the land called for planting of a thousand trees by the end of the second year. To meet that deadline planting started in the wet season when it should have started in the dry season. Most of the plants were washed away even as they were planted. Those who managed knew nothing about wet and dry seasons in the Amazon jungle. But they had a can-do attitude learned in Dearborn and they set about replicating Dearborn in the jungle with brick houses and metal roofs that made them sweat boxes. But such will power cannot overturn nature.

The jungle prevailed. While the Brazilian rubber trees seeded in South East Asia flourished because they had no natural predators, in the Amazon there were many fungi and insects that feed on the rubber tree. When planted close together in a plantation, the rubber trees perished easily and readily. The Ford company took no advice from botanists, though some did try to tell it.

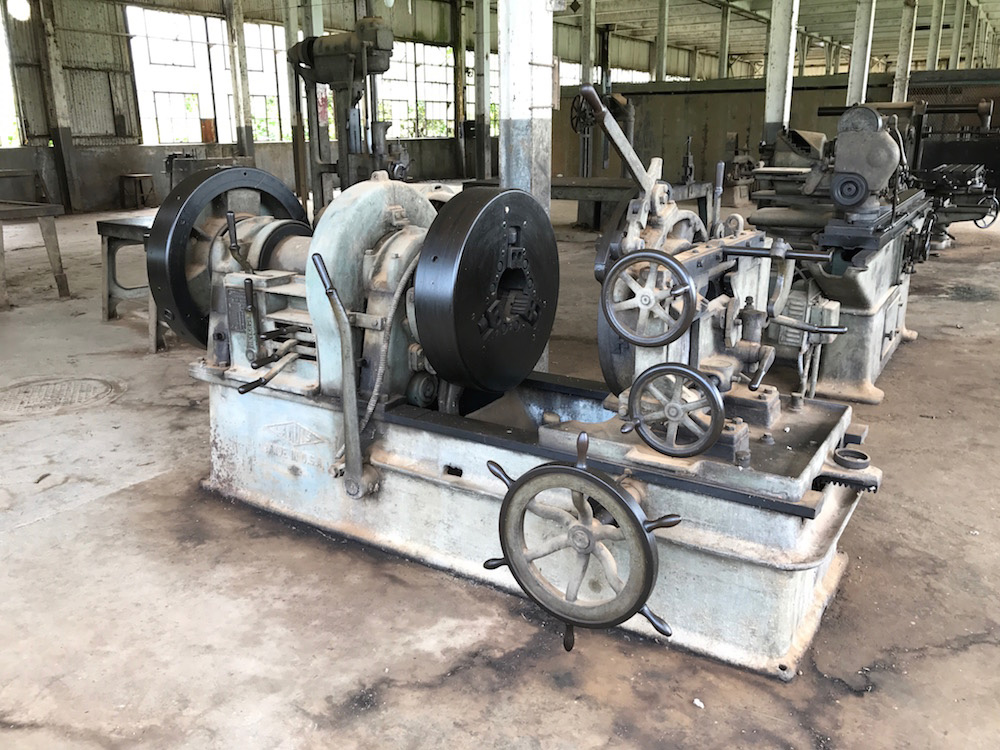

What remains.

What remains.

There are many similar stories where the assumption was that if enough money was spent, enough equipment deployed, enough men employed, then it could be done. But there was never enough to overcome the Amazon. Think Fitzcarraldo.

With age Henry Ford became more and more stubborn and less and less reasonable. What started out as good intentions in paternalism became despotic.

There was also a good deal of mission creep. The stated goal changed and changed again to avoid admitting defeat. First it was to grow rubber. Then it was to develop the Amazon interior as a philanthropic gesture. Then it was to support the Brazilian government through investment. Next it was to export the American model of community. Finally it was to hang on to American interest in Brazil to keep it on the Allies’ side in World War II.

Ruins.

Ruins.

I learned a lot from the book but I found the author’s didactic tone irksome. Rather it than informing the reader and then letting the reader decide, the moral is asserted early and often. Because of all the extraneous material as mentioned at the outset, I found the book hard to follow, though I already knew some of the story. Reading all this detail, makes me appreciate the way the novelist distilled enough for the story he told out of the morass of facts.

The obvious comparison, not made by the author, is with the building of Brasilia a generation. Although Brasilia was not built in the Amazon jungle but on a high, arid plateau in the middle of nowhere.

I found nothing that relates to utopian theory or practice.