The third in the series that I have been gulping down, one after another, ‘A Study in Murder’ once again plunges the hapless Dr John Watson, late of 221B Baker Street, into the thick of a villainous plot. Mrs Gregson is there to throw a lifeline, and the decrepit Sherlock Holmes has resources of his own to apply. The redoubtable Sie Wölfe, Ilse Brandt, continues her savage rampage. Her bodycount must have reached double figures by the end of this page-turner.

At the end of the previous volume, Watson was injured in the explosion of a tank along the Somme. He awakens to discover he has become a prisoner of war deep in the Harz Mountains. The lager is one that is hidden from the Red Cross and all manner of unsavoury things occur there. While the German regime is harsh, Watson comes to suspect the prisoners themselves are worse than the warders, English gentlemen though they may be.

The Harz Mountains

The Harz Mountains

How Watson, a geriatric, finds himself in such pickles is due to the ingenuity of the author who shows him no mercy.

Mrs (Georgina) Gregson contrives a fantastic plan to free Watson. Meanwhile, his life is made even worse by the machinations of an old enemy with a long memory who now works in German counter-intelligence. The plot is very thick. Gregson makes a tenuous alliance with Ilse, Mycroft Holmes, an MI5 man who lusts after her body, a music-hall magician, the pilot of a barrage balloon, and a cadaver. Yep. The dead can help, maybe that should have been the title here.

Holmes, they suppose, is too far gone to know or care what is happening. (Ha!)

In addition, another squad makes use of a German sniper to clinch the deal. There are many chefs in this kitchen, none with a recipe.

Meanwhile, the detective in Watson keeps following clues in the lager through cold, snow, drafts, coffins, tunnels, and hunger of the prison camp to discover…. Wheels within wheels within wheels.

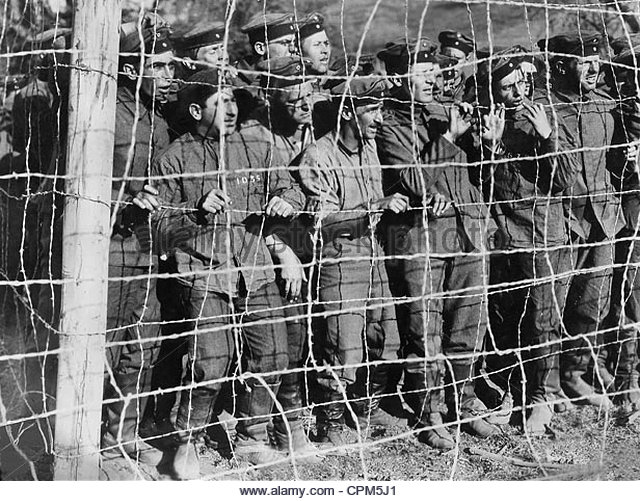

POWs in world War I

POWs in world War I

For a man of his years, Watson has remarkable recuperative powers given all the stresses and strains the author deals out to him. He is struck with a rifle butt, hit over the head with timber, pushed down holes, punched in the gut, and shot, all while living on 1200 calories a day in winter, and he keeps on keeping on. What is his secret?

With each turn of the page the brew is deeper and darker, the mix is richer and more varied. There are so many incidents and characters that sometimes the book is hard to follow. It seems to be two (or more) novels plaited together.

To this reader loose ends remained, chiefly whether Captain Brevette did indeed make contact.

Ryan is a prolific writer and has turned out a nineteen novels, four in this Watson set, as listed in the Wikipedia entry. I hope he sticks with Watson for a while longer.

When I read these, the Watson that comes to my mind is that played by David Burke in the series featuring Jeremy Brett. Note that this series was split, and two actors played Watson. Burke played him as young and more physical than most do.

The quintessential Dr John H Watson of Baker Street is, of course, Nigel Bruce. His Watson is avuncular, warm, fun-loving, roly-poly, friendly as a puppy, dopey, stalwart, bluff, predictable, banal, talkative, superficial and he went a long way to restoring Watson to the Holmes cinematic canon. That is, earlier film adaptations of Holmes stories had diminished and sometimes omitted Watson. By the way the ‘H’ stands for Hamish.

Nigel Bruce

Nigel Bruce

Moreover, Bruce’s Watson also represented the perfect foil for the quintessential Sherlock Holmes, Basil Rathbone. This Holmes is mercurial, incisive, cloaked, impatient, spare even sour, mince, cryptic uncommunicative, mysterious, and razor sharp. They partnered in fourteen films, ending only when the executive producer died, leaving no one else to champion the franchise, which in truth was tiring. The directing and acting had remained pitch perfect, but the stories, despite the oeuvre available, had became hackneyed in the effort to give them contemporary settings in the 1940s.

Nigel Bruce was the second son of a baron. But he was stage-struck as a youth and foreswore the life of the landed gentry for the theatre. He was an infantry officer in the Great War and suffered eleven gunshot wounds at Cambrai (Northern France) in November 1917. Those wounds ended any later army career. By the way, British tanks were deployed in this battle but in dribs and drabs as mobile block houses, not as a strike force.

I met Basil Rathbone at a poetry reading and I was an undergraduate in 1966.

Skip to content