Juan Perón (1895-1974) dominated the political life, and more, of a large, diverse, far flung, and advanced society for two generations, and even today his name is magic for some Argentines. He did so without coercion or force. His rule was authoritarian but not with a gun, and at least in one moment of truth when he was urged to order combat to save his regime he refused.

Ergo while he might, on some grounds, be classed with Hitler, Franco, Stalin, or Mussolini no one ever imagined such restraint from them. Moreover, while he did everything to hamstring critics and opponents, they were not rounded up and sent to Patagonia or worse on an industrial scale. Indeed, at times he boasted of the freedom conceded to his critics. If at times that was more lip service than reality, it is still not something that those others would not have done.

Nor did he unleash a social revolution to purge the society of undesirables as the dictators did. Rather he tried to balance the contending forces, seeing himself as a conductor. Indeed, he liked to be called El Conductor. The orchestral image is intentional for he always liked orchestra music for the way it blended the diversity of sounds and instruments into a smooth whole. At the start that was his aim though at the end things spiralled out of control.

Finally, there is no doubt that in his early years in government, first as an eminence gris, then a Vice-President, and then President, he had a social program to redistribute wealth to urban and rural workers. To do that he more or less created labor unions in Twentieth Century Argentina.

He was born in 1895 under the sign of Libra. As a youth he lived with his family in Patagonia for several years where they worked the land before attending boarding school in Buenos Aires. He was a poor student and on a schoolboy dare took the entrance examination to a military academy. He passed and took it as a way to escape another poor report-card from the boarding school.

He liked the order and regularity of the army and soon found himself an officer where he excelled at instruction. At the time he was popular with subordinates because he was considerate of their dignity. When a private proved inept or a made a mistake, there was no shouting or punishment. Rather, after the unit was dismissed he could call the malefactor aside and give him one-on-one instruction or correction and encouragement. This was so odd that his own superiors wondered if it disqualified him from advancement, on the other hand his unit performed above the norm, and so he continued in the army.

He travelled to Europe in 1938-1939 to visit Italy and Spain. He admired the social mobilisation and energy he saw in Italy, in contrast to the disarray of France through which he passed. He attributed the virtue of Italy to Mussolini and the disorder of France to democracy. Even more striking to him was the devastation and hatred he found in Spain; that the Spanish had nearly destroyed their own country and were so divided that they hated each other more than any external enemy left him with a lasting memory. The biographer suggests that is one reason he did not resist the coup d’état that ousted him. He had no wish to start a civil war.

The Argentine army often interfered with civil life and government and in 1929, while a young colonel, he was directed to settle a wildcat strike. He did this by negotiation and not with rifles. Odd again, but success was enough.

Later in yet another military government, someone had to be secretary for labor, a minor post at the time, and because of his success with that strike he was appointed. Rather than repressing trade unions, as other Latin American military governments did, he set about creating them. He sold this approach to his superiors and their oligarchical supporters on the ground that, while it would redistribute some wealth through wage settlements, it would produce a profitable stability in which most of the wealth would remain in the hands of oligarchs. He was quite a salesman and he prevailed over much resistance. Likewise he sold the unions to labourers as a new benefit that could be achieved now.

In this marketing campaign he perfected two techniques he would use ever after. First, he set so many hares running there was confusion among his opponents. He encouraged the formation of so many unions, that they collided with each other, and he become the umpire of their disputes. Second, he learned to play his opponents off against each other because the oligarchs were not homogenous and he saw rifts among them, and likewise within the army.

There was third technique that came later and that was simply to deny everything and start over. Like an athlete, he did not dwell on failures or mistakes but pressed on.

He might have laboured at this level for the rest of his days but for an act of god. A terrible earthquake destroyed whole cities and killed thousands in 1944. The military government had to mount an emergency relief effort far beyond its own means. Civilian help was required. Who was the man of the hour? The man with contacts among all of the unions of truck drivers, entertainers, stage hands, waiters and cooks, stevedores, nurses, porters, water engineers, sanitation workers, and other working stiffs? Came the hour; came the man.

He threw himself into the work and in those days he had a very competent office staff to shoulder the task. In no time at all a whirlwind of aid developed. He went further.

Giving a blood donation made him think of using a thermometer to chart the collection not only of blood donations but also money and two large symbolic ones were erected in downtown Buenos Aires.

To raise money and blood, gala performances by entertainers of all kinds were staged before them. He attended the inaugural event, resplendent in a white uniform, modelled on those worn by Red Cross officials, and that is where he met Eva Duarte (1914-1952).

He was called the man with the toothpaste smile.

He was called the man with the toothpaste smile.

The story goes she was one of many in a group of twenty sitting far away from Perôn at the start of the evening, but by the end they were side by side and stayed that way for the rest of her life. He had a knack for publicity with his ready smile and quick wit. She added to that timing, contacts in show business, and a sense of the dramatic. They were a power couple par excellence from that night onward.

Juan and Eva.

Juan and Eva.

The generals pushed each other into and out of the office of president, and one such elderly general left most of the work of president to his aide-de-camp, Colonel Perón, who remained simultaneously the secretary of labour creating a working class constituency for himself. That may be the wrong way to say it because there is no sense that he was planning ahead. Rather he found the exercise of managing events fascinating and discovered he could do it.

Then he was Vice President and in that position ran ever more of the government. His programs built roads and bridges to allow crops to reach cities at affordable prices, social insurance, hospitals and schools, severance pay, accident insurance, and more. He had no ideology but he saw in such measures stability and harmony.

Eva’s influence led to reforms concerning women and children, including, in time, the franchise, divorce, and creches. While he was an average public speaker, she was a firebrand and she became the voice of Perón. He was measured and rational; she was immediate and emotional. Together they covered all bases and they often spoke in tandem.

At times these benefits were reduced to meet other economic goals and he spent a lot of time explaining this to those affected. Our author suggests that in other circumstances he would have been happy to be a teacher since he enjoyed such exercises.

He made enemies, of course, and the ride was rough at times. He masked his efforts behind the smokescreen of a myriad of projects and activities. Confusion was his strategy. Divide and conquer was his tactic.

When an incumbent military government went through the motions of an election to placate world opinion and attract foreign capital, he became a candidate and the Perón and Eva combination overwhelmed opponents. He got two-thirds of the vote. He was aided by the clumsy efforts of the US ambassador to defeat him. Perón added the anti-American card to his tactical arsenal.

The suspicion existed that Perón was a fascist. His influence then explained why Argentina stayed out of World War II for so long. Leave aside the fact that Argentina had no interests involved in the war, apart from satisfying the United States. That there was a resident German colony of long standing in Argentina, come originally for engineering projects, was used to explain how he learned his fascism. Leave aside the fact that he had nothing to do with them. That together with public admiration for Mussolini’s Italy as he saw it in 1938 was conclusive in Washington.

In 1944 while the war in Europe continued no expense was spared in Washington to research captured German records to find something on Perón, producing a Blue Book that contained nothing of substance. I noticed some of this was recycled lately from copies of the same German records seized by the Soviets. The one part I read had Perón instructing Argentine diplomats to encourage French citizens who did not want to continue living in France or to return there to migrate to Argentina. He also encouraged the local German community to recruit technically skilled Germans to start over in Argentina. How damming was that! He personally did not stamp Eichmann’s passport, honest.

One of the hallmarks of European fascist regimes was social revolution that changed the society, usually by genocide or proscription. There was never any of that in Perón. On the contrary he liked diversity, the better to play one part off against another.

As president Perón put a lot of pressure on British interests, which were deeply rooted in Argentia, especially in the railroads. He did nationalise some British assets but also paid off a billion dollar debt to the Bank of England at the same time. He created marketing boards for crops and some industrial products that would negotiate international sales. One was the Argentine Wheat Board later to be the unstated model of the Australia Wheat Board.

None of this was programatic and that needs to be born in mind. He had no ideology. He just tried things, and if they worked, then fine. If not, he walked away to try something else. He had a capacity to recognise defeat and quit, unlike the ideologues today who keep trying the same thing again and again, willing it to work despite the costs.

In the Cold War he was a vigorous anti-Communist not as a matter of principle so much as because it was foreign and godless. He tried his hand at international statesmanship by giving speeches in Chile and Brazil about a third way between capitalism and communism. Capitalism in the much of South America was identified with the rapacious practices of some American businesses, and communism was anathema to Roman Catholics. He had a tin ear for diplomacy and soon gave it up.

Thereafter sports was the one field in which he promoted Argentina on the international stage, and the bid of Buenos Aires for the 1956 Olympics was defeated by one vote, and the games went to Melbourne.

He promoted economic independence in the post war world and shunned the Bretton Woods agreement that created the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the International Monetary Fund. While Great Britain owed Argentina huge sums for food imported during the war, it could not pay in hard currency. Some of this debt was offset again the British owned railroads.

Inflation beset Argentina and Perón had no remedy. Belt righting by workers was a help but not enough. Higher taxes on wealth helped but not enough. And each of these measures made enemies.

He won a second election in a campaign that was heavily restricted. Only in the two weeks before the election were political parties allowed to exist and campaign, and by then radio and newspaper were either controlled by the regime, some owed by Eva, or obedient to it.

‘La Prensa’ was a newspaper the regime targeted and one that fought back. Its resistance to the censorship of the regime, and physical attacks on its plant, rallied the international press to its side. The irony is that at the time ‘La Prensa’ was a rag (think News Limited) that supported the oligarchs but all this international attention somehow caused its writers and editors to live up to the image of embattled heroes of free speech and ‘La Prensa’ became, thereafter, as a result of this ordeal, a very fine newspaper. Something it had not been before.

A few numbers might indicate the scale of activities in his first two terms. more than 4,300 health care facilities were built and staffed. There were 8,000 new schools with teachers, and several hundred technical institutes to train nurses, mechanics, midwives, and others. More than 600,000 homes were built for low income families.

Investment was also made in industrial projects like dams and harbours.

Eva Perón created a foundation and Juan directed that a one percent of the national lottery funds go to it and influenced (ordered) the tame trade unions to see to it that their members contributed to the Foundation one day’s pay a year. The Foundation employed 15,000 people to run clinics, transport midwives, build old-age home, workers holiday resorts, build playgrounds, orphanages, and create soccer leagues. To play in the soccer leagues the boys and girls had to have a physical examination by a doctor, the first time for most of them. At practices and games they got a hot meal designed by dieticians. The Foundation paid for all of this.

She was on track to be his Vice President when cancer laid her low. Her death and the subsequent treatment of her cadaver are the stuff of legend. Juan was rendered speechless for days after her death. He who had hardly ever had a sick day refused to believe she would die, until she did.

The inescapable conclusion is that even before Eva’s death, Juan had grown bored with politics. He needed a new challenge, hence the dabble in international statesmanship, and so he provoked a conflict with the Catholic Church. It was needless, but once it started he went at it hard. proposing to tax church property. Churches were burned by some of his enthusiastic supporters whom he encouraged, though did not direct. This was madness in the confessional society that was Argentina.

His enemies who had been squabbling among themselves for years, now united behind the church. No sooner was he re-elected, in 1952 another coup succeeded. Several earlier ones had failed due to rivalries among the plotters.

There is no doubt that the Perón regime had its ugly side. Thousands of teachers were dismissed because they were insufficiently enthusiastic about Perón. More importantly, Peronism changed from measures aimed at social harmony to measures aimed at keeping Perón in office as an end in itself. The means had become the end. One of the strengths of this study of the man is that it shows how he changed. After ten years he no longer felt the need to sell his ideas. He just gave orders. He did not have the instincts of a democrat.

And Perón wanted to stay in office, not to accomplish anything in particular, but to continue to play the politics game.

To his credit, however, Perón did not fight the coup, though there were armed Peronist militias ready to do so, and he had still many army supporters in the lower ranks. Instead he went into exile. The shadow of the Spanish Civil War remained with him.

Despite all the rumours circulated by his domestic and international enemies he had no ill-gotten fortune. He lived on the largess of his hosts in Paraguay, Panama, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and finally Spain. That is one reason way he moved on each time, his welcome was worn out. The new Argentine military regime spent millions of pesos to eradicate every vestige of Juan and Eva Perón. Teachers from Patagonia to the Amazon basin spent one summer blackening their names out of textbooks. Street names were painted over. Statues destroyed. Back files of newspaper were burned. The Mausoleum to house Eva’s embalmed remains that was under construction was demolished overnight to become a carpark.

Then Argentina went through a long period of instability with coup and counter coup as the military factions brought order and discipline to the society! If the succession of musical chairs military governments promised stability, they did not deliver it. One president after another came and went. Planes bombed the presidential palace on occasion.

Naval personal kidnaped a president. Another was assassinated by a rival’s supporters. On it went.

Civilians took up arms, too, some encouraged by Perón from Spain. He termed them ‘special formations.’ Once off the leash, they stayed off the leash.

Five years after Perón was expunged from Argentina, a military government made tentative steps towards civilian rule through elections, as much to placate foreign investors as to satisfy domestic demands. From exile in Madrid, Perón advised his followers to cast blank ballots. They did and that was the plurality result, about 30%. In the rush to appear democratic that fact was ignored and a civilian government with 25% of the vote was installed and it fell at the first feather. The generals returned.

Peronism — with or without Perón — came to dominate Argentine politics. There were first those who were anti-Perón, the land owners, industrialists, bankers, intellectuals like Juan Luis Borges, and much of the older generation of the army who felt he had betrayed the uniform by siding with workers who were all closet communists. That was one-third. The Peronist made up the other other two-thirds. One portion of them were ideologues who saw a program in what the Peróns had done and these became the left-Peronistas. Another portion became followers of the man himself. Whatever Perón says goes. It was a messianic cult as much as it was a political bloc. These were the right-Perónistas. In between were the trade union moderates who concentrated on the sewer socialism of wages, accident insurance, and medical coverage. (The term ‘sewer socialism’ is explained in an earlier post on Milwaukee.)

None of these positions was satisfactory and in the 1970s the fissures opened. A wave of urban guerrilla warfare arose with the Montoneros and then their rivals. There were also armed labour factions that battled out union elections with bullets rather than ballots. Foreign investment disappeared. Inflation ran out of control. Strikes were daily. Infrastructure repair ceased, as did buses and trains. A flight of capital occurred allied with a brain drain.

In this turmoil another general-president looked to Perón for help. No doubt this general overestimated Perón’s potential influence, but Juan Perón was not going to disabuse him. Courtship was undertaken. Perón was rehabilitated, given an Argentine passport, his back pay and pension were resumed, his statue appeared once again in the line of presidents in the official residence. (What a line-up that is, since one held the office for two days and an another for two weeks between coups.)

While in exile Perón had long continued his game playing by mail, by telegram, through emissaries, while those who aspired to bask in his glow travelled to Madrid at their own expense for an audience with him.

Presidential elections occurred and Perón’s handpicked candidate, Hector Cámpora, a dentist, won a resounding victory. Perón returned, Cámopra resigned, and in new elections Perón won again, a third time. This election was much more fair than the last one in which he triumphed, but his win was just as decisive.

While exiled Perón had met Isabel Martinez (1932+) and married her. She too was a performer and bore a slight resemblance to Eva before cancer took its toll. He was 66 and she was 30 and looked younger. In no other way was she like Eva. Indeed she was very insecure about her place in Perón’s life.

Early in his career the dynamic Perón had attracted a lot of capable people and put them to work. Gradually he shed most of them, because he wanted to be the master of the situation not upstaged by any minor players, still less to nourish a successor. His entourage then swelled with acolytes, yes-men, toadies, and the like. He had little or no interest in these hangers-on but took their service – door opening, bodyguard, floor sweeping, typing, housekeeping, dog walking, telephone answering, car maintenance – for granted, though he was unfailingly polite to one and all. For an Argentine a few months in the Perón household could be translated into celebrity back home. There was never a shortage of volunteers who paid their own way.

The chronic instability of Argentina and the extremes of the military governments attracted much attention from Washington during the Cold War, lest it become another Cuba. The American interests could never find evidence to support the charge against Perón that he was a Nazi or sheltered war criminals despite much effort, nor could they ever find the illicit millions he had allegedly drained from Argentina. He lived modestly in Madrid, dependent on admirers and the Franco government. Later when his army pension was restored he wanted a lump sum for the back pay to settle debts. Though, by the way, Franco choose never to meet him in the twelve years Perón spent in Spain.

He returned to an Argentina that was demoralized, broke, and riven. Armed bands roamed the streets looking for trouble which they found. The damage done in the last coups, shell holes in buildings, and wrecked vehicles were left in situ. The army was torn by personal rivalries and enmities. After years of repression few civilians ventured into politics. It was a devil’s brew.

Yet Juan Domingo Perón became president for a third term at age 78. For comparison Ronald Reagan took office at 70 and left at 78. Perón’s heart was poor but this was concealed from nearly everyone.

The touch he had had in years gone by remained. While he could match the contradictory confusion of Joh Belke-Petersen, he had no plans and no staff to execute them. He tried to rein in the violence, much of it done in his name, by meeting leaders of the factions but without success. It was as though all waited for a miracle.

Eva’s body had an odyssey of its own. When the putsch ousted Perón plans for her mausoleum were shelved, but the body had already been embalmed for display.

No one wanted to be the one to destroy it, so it was boxed up and left in a basement marked as ‘Radio Parts.’ When a new building manager came along later, not knowing what was in the box, he moved it into a hallway to make use of the space in the basement. There it sat. By this time those who had boxed it up were displaced, some killed by rivals, others themselves in exile. Then a new Minister took office and wanted to reorganise the building. The box was a fire hazard in the hallway. He ordered it moved. To move it the workmen decided to open it. Surprise!

The box was quickly sealed and put back in the basement while the matter went to then president. Before he could act, there was another coup and there followed another pause. Then it was decided to bury her, but not in Argentina. The body was transported to the Argentine embassy in Rome and then buried in Milan under her mother’s name.

Were she buried in Argentina the location would inevitably leak out and then most likely become a site of pilgrimage for Peronistas. Hence the decision to send the remains abroad. Argentina had good relations with Italy so blind eyes were turned and the deed done.

When a moderate general=president restored Juan’s citizenship and pension, the general-president also arranged for her body to be disinterred in Milan and delivered to Perón in Madrid who accepted it and put in an unused bedroom upstairs, where it stayed even after he returned to Argentina with Isabel.

While the body was in the bedroom, one of the entourage who dabbled in Brazilian black magic convinced Isabel to take part in seances, let us call them, to conjure Eva’s spirit into her own body. The individual in question was certainly nutty enough to do this and Isabel was very easily led, so she may have played along in the hope of securing her position as Perón’s paramour. (Argentine’s are quick to label anything they dislike as Brazilian.)

Shortly after the third election Perón had a serious heart attack, that sapped his vitality. It seems to have been a spontaneous gesture by his supporters to put Isabel on the ticket with him as Vice President and he had let it ride.

Isabel.

Isabel.

The author is sure it was not his intention to elevate her because he was using that card to tempt and control rivals. That dabbler in the black arts, Daniel José López Rega, became his personal private secretary and controlled access to the man himself.

He was 73 in this photograph. Hair dye?

He was 73 in this photograph. Hair dye?

Perón had no new cards to play and the 1973 oil shock hit hard. The armed conflict continued, mostly between the ideological left Peronistas and the trade union Peronistas. Many believe López Rega formed the first Death Squads and turned them loose on one and all. Rather than peace and stability, Perón’s return led to an escalation in violence.

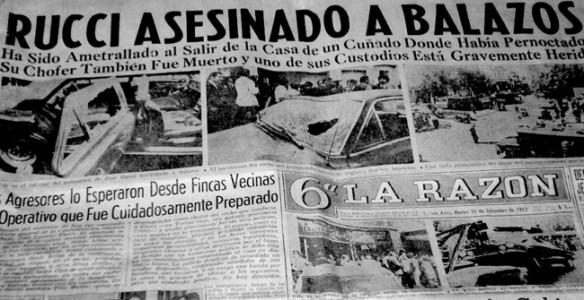

Yet another murder.

Yet another murder.

He worked hard in his third term, but to little avail. Then in June 1974 he had a series of heart attacks and on 1 July 1974 he died. Millions mourned Perón. Isabel succeeded him, and she was heavily dependent on López Rega and the state terrorism became systematic. The Dirty War had begun. In March 1976 yet another coup d’état displaced her. By the way Amnesty International estimated that the Dirty War killed 30,000, imprisoned a multiple of that, leaving them scarred, and intimidated most of the population. Though what is was about is lost in the mists. It became score settling as end itself, and discredited most state institutions, the police, the army, government officials, and school teachers for the subsequent two generations.

A crowd to hear Eva speak.

A crowd to hear Eva speak.

The word ‘charisma’ is so overused I am reluctant to employ it but that does seem to be the word to use here. Juan bore a message and for a while subordinated himself to it. Eva added an emotional touch to that. It was interpreted as a message of hope by the rural and urban working classes. He delivered a lot to them, certainly more than ever before or after. It is estimated that about a third of the nation’s income was redistributed, directly in income, to these peoples, and more indirectly through the social welfare programs.

He also had John Ford luck, a phrase from Hollywood that explained why the sun always shone when Ford scheduled out door filming. When Perón had an outdoor rally it never rained and always shined. So it was said. He was personally attractive and a tireless worker.

But his luckiest break was to be in exile when all the wheels fell off, so that he was untouched by the endless corruption and conflict of that seventeen year period. Though experienced and connected he returned with clean hands.

On the debt side is his later preference for sycophants and his willingness to encourage violence, perhaps on the mistaken assumption he could quell it with a word. He could not.

He was an authoritarian populist who did deliver to his supporters, but less and less. He gave no thought to succession. Isabel was in way over her head. Unlike Salazar of Portugal, Perón was bored by routine. He never quite had the grip on sprawling Argentina that Salazar had on compact Portugal and so devoted an inordinate amount of his time to securing his own position and over time that displaced any social or economic goals.

No doubt there are those who know this era of Argentine history better than do I, because they have seen the movie! But I am reminded of the film reviewed elsewhere on this blog, ‘The Secret in Their Eyes’ which offers insight into Argentina after the ‘Dirty War.’

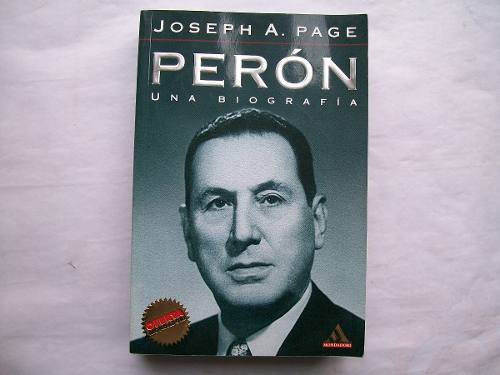

This is an excellent book. Carefully phrased, thoroughly research, slow to judgement, and measured in expression.

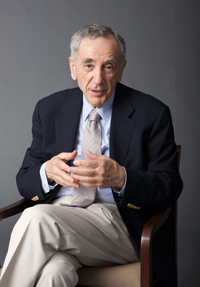

Joseph Page

Joseph Page

Chapeaux!

Skip to content