The word ‘Timbuktu’ entered vernacular English in 1863 as the most distant place imaginable, according to the OED. It has had many spellings over the years but the one used here is the standard in Wikipedia. Most who have heard the word take it to be mythical, but in fact it can be found on a map, in the sub-Sahara West African nation of Mali.

Timbuktu gained some recognition among the Nerd Empire in the late 1990s for the collection of medieval and even ancient manuscripts gathered there, and more when these treasures were threatened by fundamentalists whom god had told to destroy all. Not all the nut cases are in D.C.

A building in Timbuktu.

A building in Timbuktu.

The airport at Timbuktu

The airport at Timbuktu

This book combines the Nineteenth Century story of Europeans exploring the interior of Africa to find this very place with the Twenty-First Century story of saving its aforementioned records from the flames.

The quest for this African El Dorado began in the mid-Victorian period when intrepid chaps in Britain were looking for new adventures. Africa, the dark continent, beckoned. It was called the ‘dark continent’ and ‘darkest Africa’ not because of the colour of the skin of the natives but because it was unknown, in the dark. There was plenty of racism but this term was not an instance of it at the outset. Later, yes, certainly. say as it was used in the 1950s in Disney cartoons.

In part the book traces the efforts of the African Association in London to explore, map, and study Africa, partly directed by the affable Joseph Banks, who as a young man had accompanied James Cook on his voyage to Australia, and after whom Bankstown is named, along with flora. The method this private organization took was to recruit a series of intrepid men and send them off one-at-a-time. Off they went and mostly disappeared into darkest Africa, never to be seen or heard again. Disease, dehydration, animals, sand, stupidity, accidents, villains got them one after another. Inevitably, a Société d’Afrique in Paris got into the game so that the rivalry between England and France was played out on the way to Timbuktu. Then came the Germans looking for that fabled place in the sun.

On the other hand is the story of the threat posed by fundamentalists, which is told in the choppy and breathless manner that distinguishes contemporary journalism. It is a sandstorm of names and places that mean nothing to this reader, and at no point is there an orderly exposition of what the manuscripts, papers, and documents are, how they came to be in Timbuktu, and who had formal responsibility for them. Nor is there anything more than the repeated assertion that they are valuable to justify the importance assigned to them. In the telling, it sometimes seems this town on the sand just by chance was home to a number of private collectors who had somehow gathered the written material and at other times there are references to libraries, catalogues, steel boxes, and UNESCO grants. Later there are few references that indicate that Timbuktu became a centre for learning in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, but by then I was so lost it did not help.

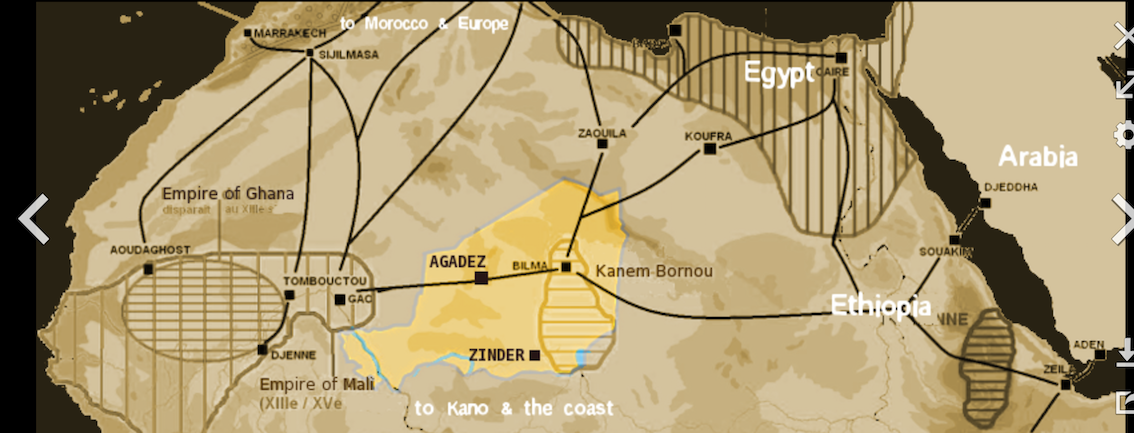

This map below from Wikipedia shows when and why Timbuktu (Tomboctou) was an important crossroads that benefitted from proximity to the mighty Niger River, from which proximity it also suffered when the river flooded. The lines are trade routes used at various times.

That combination of two stories is both an asset and a liability. It is an asset because it makes clear the importance of Timbuktu and its holdings and a liability because the author has a lot more to say about the latter story than the former and so it is unbalanced.

Trashed books in Timbuktu

Trashed books in Timbuktu

While the telling is repetitive and confusing at times, the subject is so important that I tried to persevere through all the confusion that the author reproduces.

There is a shower of proper names, descriptions of men with guns, the arrival of trucks, comings and goings as though this is a thriller. Well it is a mystery to this reader. One that remains unresolved.

Charlie English

Charlie English

I supposed the author was a journalist from the disjointed style, the disregard for readers, and the indifference to exposition, and then I checked. Sure enough. He and this book get a lot of space on the ‘Guardian’ web site. Make up your own mind. I have. With perseverance I made it about halfway through before deciding I would learn more reading Wikipedia. No doubt Good Reads is replete with fulsome comments. No doubt the dust jacket of the hardcover proclaims it a best seller. No doubt.

Skip to content