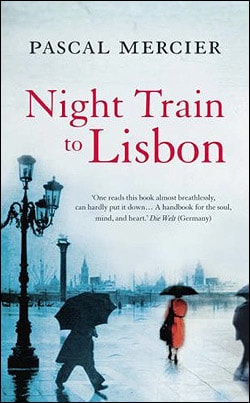

Raimund Gregorius, known as Mundus, teaches dead languages to gymnasium students in contemporary Berne, Switzerland. He eats and drinks dictionaries of ancient Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, barely noticing when his wife leaves him. His only topics of conversation is the ablative case in Latin, declensions in Hebrew, and inflections in demotic Greek. He can bring boredom to any dinner table and so is invited to few, well, none.

Think Immanuel Kant, Mundus is a man of unvarying routine, a routine not interrupted by the aforementioned wife’s departure. Every morning at 8:15 a.m. he walks across a bridge to the school, where students and staff are silently agog at his myopic intensity. This he has been doing for thirty plus years for he is now fifty-seven.

In the rain, with wind inverting his umbrella, he trudges to school with a brief case full of marked essays to return to students whose every error, great and small, has been meticulously annotated, and he has prepared a lecture on the main themes in their work, mostly about their errors, which lecture he calls to mind as he wrestles the umbrella.

Losing the battle with the wind, he sees ahead a woman in a red coat, standing next to the bridge rail in the rain staring at a piece of paper. (Immediately I saw Irene Papas in the rain from ‘Zorba the Greek.’) The rain continues and the paper is sodden. Is she going to jump off the bridge into the gorge? He quickens his step; as he approaches he can see the ink running on the page. He looms up and she is startled out of her reverie and in reaction he drops his brief case spilling out the essays. In the ensuing confusion he takes her to a coffee shop across the bridge to regain composure. Even before getting away from the rain she extracts a piece of paper from him and writes down a telephone number, which in the coffee shop is copied again on a dry piece of paper, while Mundus sweeps the sodden copy along with escaping essays into his brief case. She keeps the telephone number once it has been transcribed.

They speak French and he discovers that she is Portuguese. He takes her along to the school where she can dry out in one of the women’s cloak rooms. He is thus late for his class; moreover the janitor is stunned to see Mundus late AND in the company of this woman, dripping on the just mopped floor. She goes off to dry, and with a word of thanks leaves. Enigmatic.

He goes to the classroom and thinks about what he has just seen, and done. He did not ask her the obvious questions. What were you doing standing there on the bridge. What is so important about that telephone number? Who are you? What is a Portuguese doing in Berne? He has spent his life not taking an interest in others and does not start now. Yet he cannot let it go.

As he hands back the essays, he notices the wet paper with the telephone number on it. (The pedant in me wondered how he could tell it was a telephone number, and not an account number, or social insurance number, a series of soccer scores, or…. ) He stumbles through the morning double class, quite uncharacteristically letting errors go unmentioned, and then goes to lunch. Ah, the life of the scholar.

This man is a loner and seldom mixes with others. On that score he has reverted to routine. He sits in another café letting the food and drink he ordered get cold: Portuguese, a Romance language derived from Latin, but that is all he knows. Instead of eating he goes to a bookstore that specialises in languages and finds Portuguese books. As a scholar he relates to books. He does not look for Fado music, or a Portuguese restaurant, or DVD of Lisbon travelogue. Bored on a rainy day and in awe of Mundus, of whom he knows, the store owner, who just happens to know Portuguese, reads some passages to him from a book of reflections, the substance of which reminded this reader of Michel Montaigne’s musing on life. Mundus likes both the sound of the spoken Portuguese and the musings which owner translates for him. He buys the book, along with a Portuguese dictionary and grammar and goes home, blowing off his afternoon class. This is the first class he has ever missed.

Overnight he begins to learn Portuguese. That may sound impossible but Ekkehard with whom once I shared an office in the Netherlands was a linguist who soaked up a language like a sponge. After a few days in the Netherlands he was speaking Dutch. Mundus finds the train connections to Lisbon by telephone (no internet for him) while dodging inquirers from the school come to look for him at the door and on the telephone, and he sneaks out of his apartment to go to Lisbon! By train. At night.

He has that telephone number. He has that book of musings. But why is he going? He asks himself that very questions more than once. He does hesitate but on he goes.

The local takes him to Geneva, where he changes trains for Paris, where he will change again for Irún in Spain and then on to Lisbon. While he rides he reflects on what he has left behind, a routine set in concrete that contains within its walls more sub-routines, and nothing at all, a series of nested do-loops that lead nowhere.

A European train station at night.

A European train station at night.

Mundus’s recollections of academic conferences, seemed familiar. All those people trying to prove (to themselves as well as each other) how smart they are. Yes, the one-up-man-ship is eternal, phrased ever so politely and usually by reference to some obscure secondary source from a foreign language. Who needs primary sources, after all. But also all those smart people for whom the subject is simply a commodity, today it is Louis Althusser and tomorrow it will be Michel Foucault, and then Jacques Derrida, with no inner feeling for or commitment to the subject matter, despite the ritualistic mouthing these days about passion. The passion is always about the ego, the self, not the subject. Though such poseurs would be the first to decry universities advertising degrees like products, they themselves approach their subject in the same detached way.

Mundus nails many academic pretensions on show in any seminar or conference.

– the high-flown gibberish that means nothing outside the classroom and very little within it

– French notions introduced as seasoning not substance, and unnecessary at that

– study is not fodder for an academic career, it is life itself with colour and melody to which a reader submits but does not conquer

Amen, Brother Mundus.

In Lisbon he begins to investigate the author, Amadeu de Prado. and pieces together his biography. There is detective work here, and the characterisations of the still-grieving sister thirty years later is a masterpiece as also some of the surviving school friends, especially Maria.

Lisbon

Lisbon

Amadeu is Mundus’s alter ego, yet he, too, was a creature of habit. Amadeu lived through the Salazar years and like all Portuguese still bears the marks of those days, good and bad. This is a new world to Mundus as he interviews family, friends, teachers, and others who knew Amadeu, who died years ago of a brain disease. Amadeu’s life is a microcosm of the life in Novo Stato of Salazar in his latter years with the PIDE, the secret police, had a free hand.

In Lisbon he makes no mention of the mysterious telephone number or the woman in red on the bridge who was the catalyst, but only that it seems. Indeed he stops thinking about her altogether and she does not reappear. If she did, I missed it, as explained below.

The musing is beautifully realised. Particularly striking to this scholar was the exchange of letters with the head of the school he left behind. When I mentioned this novel and this episode in particular to a lunch gathering of jaded scholars, there was a respectful silence, which I took to be each imaging the exhilaration that would follow walking away from a yet another pile to essays to mark, yet another pro forma about key performance indicators, yet another research grant application, yet another decanal briefing.

All that and more is true, but it does seem to go on and on for 4 5 8 pages. Mundus wanders through Lisbon, travels to Coimbra, and Finessterre in Spain, following links in Amadu’s life. Then he goes back and forth to Bern and…..THE END.

Like a bad student, doing a reading assignment badly, I kept watching the percentage tick by on the Kindle, ever so slowly. I kept at it because of the jewel like prose, the insights into friends, filial love, comradeship, chance, and so on, but there is no narrative drive. All trip and no arrival.

Pascal Mercier.

Pascal Mercier.

The story is very well measured and the prose is exact, and yet a certain mystery remains. The film derived from the novel passed through the Newtown Dendy a few years ago and I was tempted by the prospect of a European travelogue but put off by the prospect of watching Jeremy Irons for two hours. Seeing him always makes me think, and no doubt this is just me, that he has haemorrhoid pain which he manfully bearing, just short of grimace.

The travelogue reminded me of my travels in those parts. I went to Geneva (from Zurich) by train to burrow into the archives of the League of Nations housed there by the United Nations when I was investigating the International Brigades for ‘Fallen Sparrows’ (1994) and then on by train to Neuchâtel to see some Jean-Jacques Rousseau manuscripts, an article based on this study appeared later. To this nerd boy both were thrills. In Geneva I found a 3” x 5” card file prepared by a Greek diplomat in 1939 of individual Brigadiers walking out of Spain to France: name, nationality, age, gender. Nothing much but authentic to the touch. Each soldier an Odysseus and few with an Ithaca to which to return. In Neufchatel I held in my hands, there being no requirement to wear gloves, pages that Rousseau himself had written. He would go on and on for pages after page of quarto, say thirty of them, and then there would be one cross-out, the prose just flowed from his quill in a steady pulse for twenty or thirty pages before it hit a rock. These are nerd-boy thrills.

Moe recently we took a night train from Amsterdam to Prague and back with DeutscheBahn. We did not do much musing. On boarding there were no directions or staff, but everyone with heavy suitcases, narrow corridors, and tiny compartment numbers elbow high. The compartment was a broom closet and the train was boiling — it must have been sitting in the sun for hours. Food was nearly non-existent. But there was worse. The toilet. [Gasp!]

The Man in Seat 61 recommended this service, and said it stopped four times. Get a new abacus, Mate! It was twelve times, each punctuated by bells, whistle, red flashing lights, and much yelling, no doubt all dictated by safety. We arrived exhausted and swore off such travel.

Skip to content