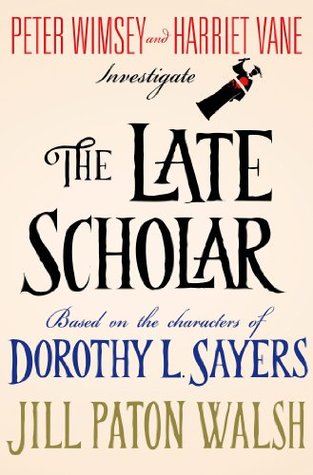

It had to happen sooner or later. Lord Peter Wimsey has become the Duke of Denver, upon the death of his older brother Gerald. That dukes are higher than lords is news to me.

With the title Duke comes ducal responsibilities, most of which were new to Peter Wimsey. There are vexatious relatives, disputatious tenants, ravenous charities, clogged drains in the strangest places, a crumbling pile that is crumble still, elderly retainers to retain, so that when he is called to Oxford, off he goes! What a relief!

When he was but a lord, to him the relatives were polite, the tenants deferential, the charities distant, the drains unknown, the ancestral pile was for holidays, and the retainers retained. As duke, it all changed.

Called to Oxford? One of the Duke of Denver’s entailments is to be The Visitor to a not very distinguished college at Oxford. While every other Oxford college Visitor is a royal of one magnitude of another, this college has the Duke of Denver. Investigation in the muniments room of the aforementioned crumbling pile reveals that generations ago a Duke of Denver handed over some dosh to replace a roof or two at the college and in return for that largesse the title The Visitor was bestowed upon him for his lifetime, but in a subsequent change of the college constitution the limitations ‘his lifetime’ was omitted, perhaps by error.

Well, no matter, an escape to Oxford is most welcome for the poetry quoting, incunabula collecting, Saxon speaking Wimsey. It is a return to lost youth for this old soldier.

Peter is now married to Harriet (née Vane) and it seems to be after World War II and in the early 1950s. The stately home is crumbling in part because of a fire caused by an errant German bomb and taxation is vexing.

Together they descend on the college to find themselves in the middle of an acrimonious and bitter conflict among the twenty of so fellows of the college over the status of a tenth century book in its library. The conflict is so vitriolic that no one speaks of it! Immediately I found this scenario easy to believe.

These scholars seem to do little else but plot one against another, while seldom is heard a discouraging word from their lips. Backstabbing, undermining, poisonous rumours, slanderous gossip, attribution of venal motives, all communicated by innuendo and sotto voce, these are the weapons of choice. Meanwhile, at high table meals the weather is much discussed. This is brutal realism at its best.

Even the engineers and economists among the brethren have taken sides over this book. On the one hand, the goal is to sell the book to raise money for yet another roof and on the other hand is the over-our-dead-bodies group! Yep, prophecy there.

Each fellow votes in a time honoured, and otherwise incomprehensible, arcane ritual and each poll results in a tie. After three such votes, some of the parties invoke the right to summon The Visitor to adjudicate. Enter the Duke!

While the vote remained tied in those three rounds, the constituency shrank. The senior most fellow, the Warden, went missing and another died falling down stairs. Two others had unlikely accidents, which while damaging, were not fatal, but which precluded participation in the voting ritual. In the best tradition of krimis the ritual does not admit of absentee or proxy voting. Is someone mowing down the voters? Are there two mowers, one on each side of the question, the keepers and the sellers? Are there only two sides to the issue?

Before any Solomonic adjudication can occur there must be sleuthing to find out what is going on.

Harriet takes no convincing to join in, and engages her own distaff Oxford network, and the ever reliable Bunter mines the college servants with his usual dexterity.

Nothing is what it seems to be.

As in C.P. Snow’s Cambridge novels, all of which I have read [Groan!], the scholars do little scholarship but make an enormous fuss over the rituals and prerogatives that fall to them, like passing the port. It is all too credible.

Dorothy Sayers created Wimsey in the 1920s.

While Ian Carmichael brought him to life on the small screen in the 1970s.

Ian Carmichael as Peter Wimsey

Ian Carmichael as Peter Wimsey

Bunter was an older man, and he and Wimsey had been through trench warfare in Flanders together and had survived, thereafter bonded for life, and with a considerable amount of unspoken communication.

Despite the dreadful experience of Flanders, Wimsey (and for that matter, Bunter, too) remains Edwardian in manner and morēs. Wimsey is an enthusiastic and effete dilettante, who quotes obscure poems in dead languages and playwrights unknown all the day long while playing the piano and sporting a monocle. His private collection of incunabula is the envy of museums. His flow of witty banter is without end and without purpose. Noel Coward could not have bettered him as a caricature.

Bunter unfailingly addresses him by his title and always stands in his presence. Always and always. Bunter out butlers even that fellow James Stevens in ‘Remains of the Day’ (1989).

Harriet, mindful of her own modest origins, tries after a fashion to loosen them both up, with little success. Nor does she seem aware of the changing times of the 1950s.

The unalloyed Edwardians Wimsey and Bunter are an odd couple in world of a Labour government and many new social attitudes. Still that is part of the fun.

Like Sherlock Holmes and more recently Hercule Poirot, Wimsey has his re-animators. This is the fourth title by Paton and I have liked it enough to read another. Though I did find it wordy, but Peter is like that. There is much talk, often about nothing much, and too little detection. It must be struggle to be arch and witty when talking about staircases and fence posts, but Wimsey is made to do it. Poor fellow.

Jill Paton Walsh

Jill Paton Walsh

He even indulges in the future subjunctive interrogative at times, such is his mastery of all things Fowler. (Mortimer, skip it. It would take too long to explain.)

Even in the sleepy village I know well, the absence of the senior scholar for three months would be noticed and some effort made to figure how what happened to the missing savant lest the key performance indicators be spoiled.

Skip to content