A pair of micro-budget parodies of big budget science fiction movies that offer more diversion than most of the films they mimic. Indeed while composing these bons mots I (tried) to watch ‘Saturn 3’ (1980) with Kirk Douglas and Harvey Keitel. It has a big cast, all that hair from Farrah Fawcett, and a big budget and set designs beyond the pale. It is pretentious and portentous. Now if it just had a story, a sense of humour, a purpose….something. I flicked away after twenty minutes. That the screen play was by Martin Amis probably explains all of that. (I tried reading one of his novels year ago, and it felt good when I stopped.) While enduring it I found a review from the doyen of reviewers, Roger Ebert, who mercilessly caned it. Amen, Brother Roger.

The ‘Space Invaders’ are the Z-team from a Martian armada bound for Alpha Centura. This hapless crew mis-read the map (upside down) and missed the fleet rendezvous (awoke too late) and is roaming around (lost in space) trying to catch- up, meanwhile exhausting the fuel. Think of those laggards with the Spanish Armada in 1588 who stormed ashore in Norway to… I was told once that the genetic inheritance from these dimwits explains both the swarthy genes and the stupidity of some Norwegians. It was Swede who passed the word on this.

While tooling around in the flying saucer the spaced-out invaders intercept a broadcast of Orson Wells’s ‘War of the Worlds.’ It being Halloween a local radio station is airing an old recording for the occasion. These dolts from space lock on to that signal and land in…Hicksville Illinois, blasters drawn and ready for a fight. It is Halloween so one and all are decked out as the weird and wonderful; ergo they fit right in. What if the Martians invaded and no one noticed? They did. They didn’t. Just as well because a dolt forgot to charge the blasters.

Moreover, the townsfolk are in an expansive mood because an off-ramp from the I-80 has been built which will bring untold tourist wealth to this dying farm town when motorists fill one tank and empty another. (Think about it, Mortimer.) A few odd little guys in strange costumes are most welcome.

The cast of small town inhabitants is marvellous. The wannabe dumb blonde who cannot quite conceal her superior intelligence but irony is not something much noticed. The shy gas pump jockey pines for her but she’s out of his league so he studies advanced physics journals between horn honks for service from the town bullies. The jostling among the local magnates to take credit for the off-ramp goes on in costume. Then there is Royal Dano, instantly recognisable and whose memorable name is never remembered, as a cantankerous farmer who is about to lose his farm to a slimy small-time, small-town developer.

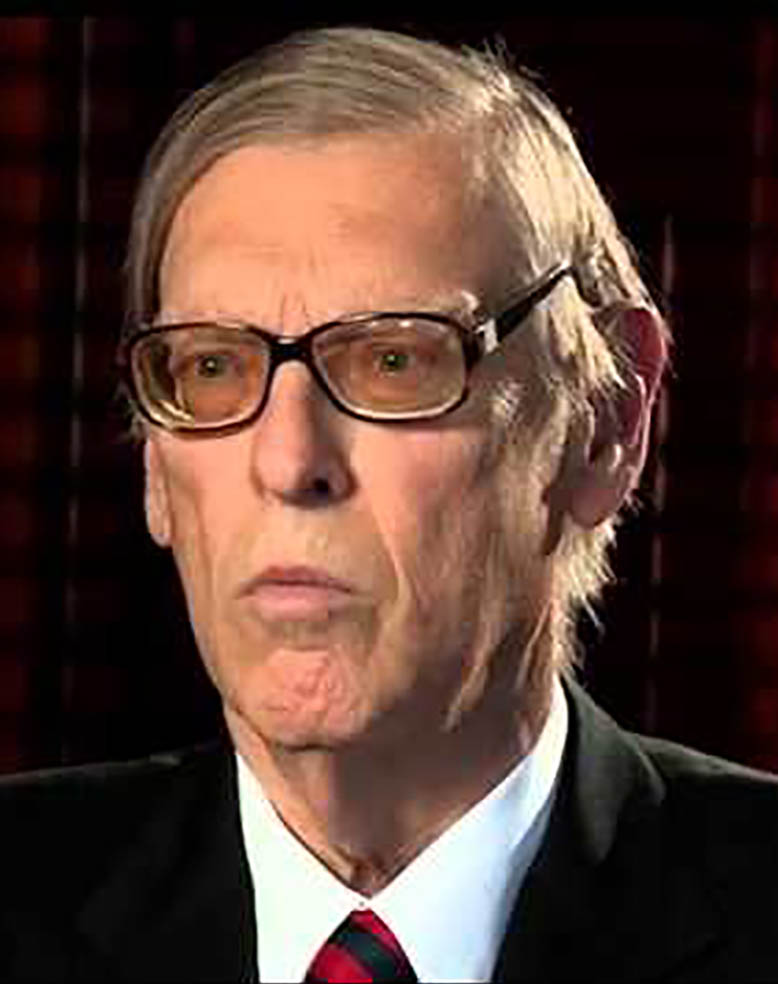

Dano in conference with the Xers.

Dano in conference with the Xers.

Vainly trying to keep order in this mix — the farmer has a shotgun or two and the developer has a bulldozer — is the lantern-jawed sheriff whose ten-year old daughter really likes the costumes of the Martians. Upon discovering they are not costumes, she says, ’They’re not bad. just stupid.’ Very.

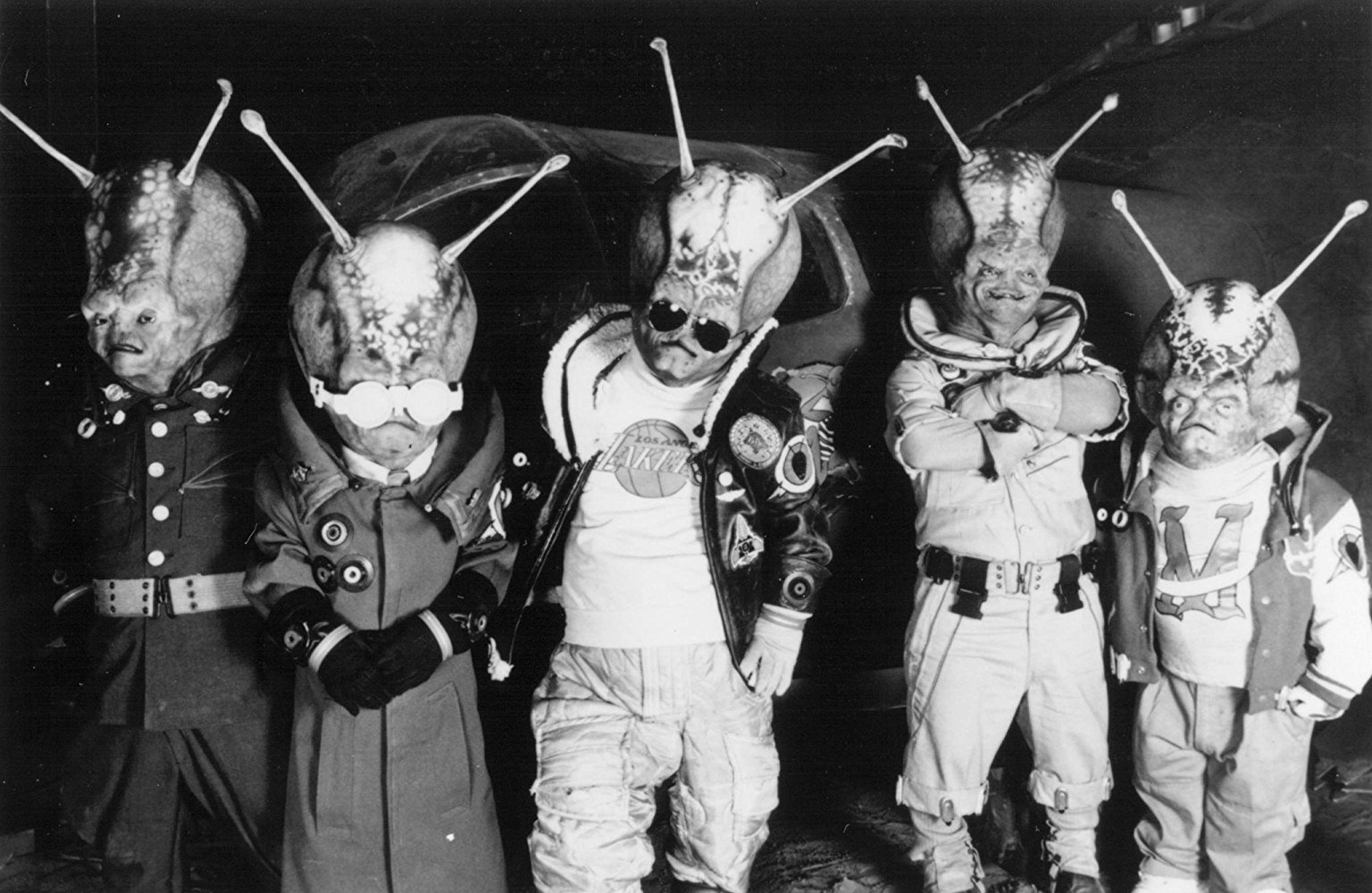

The Z-Team.

The Z-Team.

Delightful mayhem ensues. The off-ramp is offed. The developer loses his shirt and much else. The dizzy blonde figures it out. The gas pump jockey discovers the inner he-man. The angry farmer has the means to put things right. (Think silos.) With his help the Spaced Invaders might be able to catch-up with the Martian Amanda, or at least get to Norway and enrich the gene pool.

Segue.

‘Dark Star’ started as a student project by John Carpenter who went on to bigger but not always better things.

It is refreshing change of pace from so many portentous and pretentious A and B science fiction films about the meaning of life or the end of the world. Oh hum.

This entry is strictly working class. Five grunts who share a disheveled and no doubt odiferous dorm room on a space scow go about their business obliterating planets with smart, and talkative, bombs. They are galactic garbage men clearing up the detritus. That the planets may or may not be inhabited is of no interest to them. The planets are in the way of West-Connex and have to be demolished to create a space route. Sydneysiders know all about this mega road project which is consuming whole suburbs in its path. It is the local version of Boston’s Big Dig and has been in the offing even longer than that behemoth.

Cinephiles will think of the later ‘Quark’ (1977), but Quark was not working class. A garbage scow yes, but piloted by the well-spoken, highly educated, very clean, and aspirational Richard Benjamin who hopes for a promotion and a better assignment. None of that fits ‘Dark Star.’ This crew has topped out with Dark Star. Their career and life trajectories are down, not up.

On board Dark Star an industrial accident has killed the captain but head office demands that the remaining crew press on, though the faults on the ship multiply, even as their budget is cut and cut again. Situation normal.

To relieve some of the boredom one member of the crew has a pet. Which tickles. Even in elevator shafts. Has to be seen.

Meanwhile, systems on the ship malfunction, but appeals to head office for permission to put in for repairs are denied. Off camera I imagined the suits in the boardroom suppose the ship, Dark Star, is beyond repair and that these working stiffs are expendable. The crew members are contractors, so there will be no payout to beneficiaries. Managers managing.

Indeed most of the events can be explained from the McKinsey management manual, though it is well before the Age of Managers Managing. Shiver! That would make a slasher movie.

It all finally comes to a head …. There is a Silver Surfer at end. Intriguing that.

Apart from the gung-ho talking bombs, and the tickler, another high point is the sound track, most of it written and some of it performed by John Carpenter before he turned his hand to slasher movies with which he made a killing.

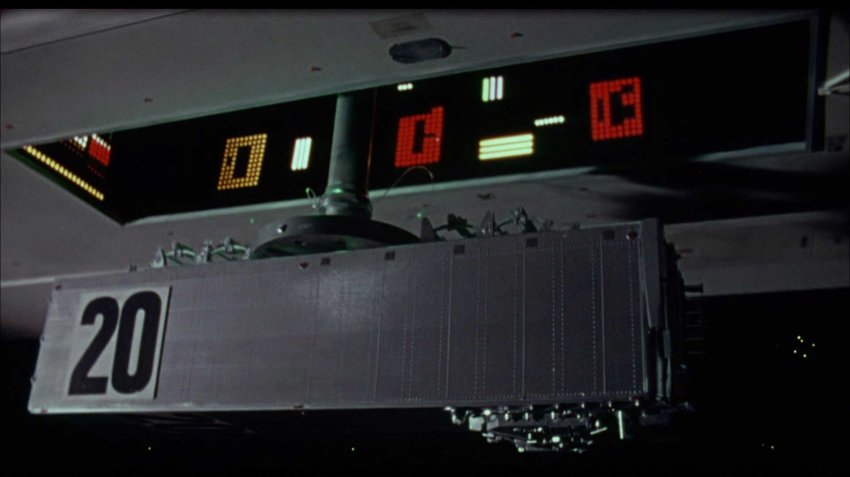

One of the smart (-mouthed) bombs.

One of the smart (-mouthed) bombs.

Roget Ebert liked it and that is all I needed to know.

A misleading lobby poster. There are no zapping flying saucers chasing Valerie French in a bathing suit.

A misleading lobby poster. There are no zapping flying saucers chasing Valerie French in a bathing suit. You have the power! (An early iPhone advertisement?)

You have the power! (An early iPhone advertisement?) Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand Arnold Moss (1910-1989)

Arnold Moss (1910-1989)

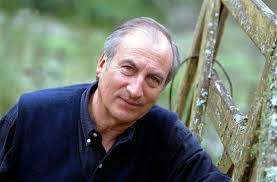

Gervase Phinn

Gervase Phinn

Fred Vargas, whose books have been purged from ideologically pure women’s libraries because of the name Fred. Amusing, n’est pas?

Fred Vargas, whose books have been purged from ideologically pure women’s libraries because of the name Fred. Amusing, n’est pas?

Kelly at work.

Kelly at work. Colebatch is a widely published poet.

Colebatch is a widely published poet.

Perón always kept dogs and could be seen walking them in Madrid.

Perón always kept dogs and could be seen walking them in Madrid. Eloy Martinez

Eloy Martinez