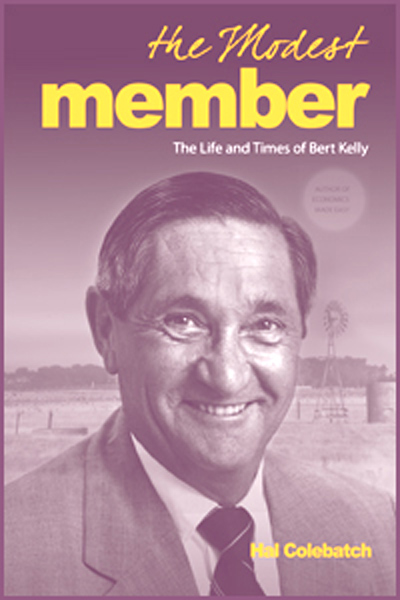

Charles Robert ‘Bert’ Kelly (1912–1997) was a farmer from South Australia. A Liberal, he served twenty years in the Commonweatlh Parliament, where he waged an often solitary battle to lower tariffs, which he thought kept Australia poor and some in it rich. A ‘Liberal’ from a farming constituency was a rarity in his day during the agrarian ascendency of the Country Party of Jack McEwan. Kelly did not set out either to be a parliamentarian or to be a Liberal but became both.

He became a parliamentarian this way. In his community he kept going to meetings and making ever modest suggestions, until others suggested he chair the meetings, perhaps as a way to shut him up. After making so many modest suggestions he could hardly refuse, so he did. Because he liked people and he liked agreement, he found the basis of agreement and that him popular in a modest sort of way.

All modesty aside, his father was very well connected and some of father’s friends saw the potential in young Kelly. In time these elders as well as his peers thought he was the man to nominate as the Liberal Country League candidate for the Commonwealth parliament. That is what the party in South Australia was called at the time, ‘Liberal Country League.’ He won as was predicted. In 1959 the Australian Labor Party had no chance in any rural constituency. Off he want to distant and foreign Canberra.

There he found the Liberal Pary and the Country Party were distinct entities, each having its own caucus, \ meeting room, and pecking order. Which was he, Liberal or Country? To McEwan any rustic came to Canberra to be his pawn and nothing more, so the Country Party sat back and awaited Kelly’s obeisance. Liberals in contrast were nice to him, helped him find his way in the labyrinth of (Old) Parliament House and more. There is no sense that this hospitality was a scheme, it just happened that a couple of avuncular Liberals befriended this young fellow wondering about Parliament House looking lost. What is implied is that the iron fist of McEwan, a man who had dominated Prime Ministers three, alienated Kelly from the zero hour. True or not, it is charming story that makes a point in a modest way.

For much of his subsequent career Kelly was the only Liberal of and from the bush. In time that gave him both an authority and an advantage. The authority was that he became the Liberal Party’s expert on agriculture. The advantage was that he represented Liberal wedge in the bush, one that some Liberals wanted to increase so holding on to him was an asset for them. Modest though Kelly was, he played both cards astutely over two decades. Yes other Liberals represented rural areas, but most of them were Bourke Street farmers, who visited the constituency a couple of times a year. Not so Kelly who continued to live on and work the family farm. Accordingly, he had an interest and a knowledge of agriculture few Liberals could match.

He went at being a parliamentarian the same way he went at farming, from an hour before dawn to an hour after dark. He was always a reader, and he found much to read in the parliamentary papers and so he read it. In time he became a self-taught economist specialising on one theme, tariffs and protection. The Great Tariff Wall of Australia did not make sense to him. While he was no advocate of free trade he did question the blanket and often secretive approach to tariffs. Though the words are not used in these pages, it seems he also supposed that the constant lobbying for tariff protection led to graft and corruption both among politicians and administrators.

And who was the dark Master of the Tariff in Liberal hegemony? Black Jack McEwan, that’s who! I was told once that the sobriquet ‘Black’ referred to his temper not his appearance.

From the first weeks when Kelly began to ask about tariffs, McEwan marked his card. Then came the Yellow Card in the form a visit from the then Deputy Leader of the Country Party and a McEwan acolyte. The message was ‘Shut up.’ Still Kelly kept reading, annotating, and asking. The details were so complex in time he changed his focus to the indirect questions of procedure. How were the levels set and for what reasons and then how were they implemented?

In retrospect the secretiveness of this process is surprising. Special Advisory committees with no tenure and no professional support from economists were created and then set the levels without either publication or justification. Again it is not said, but the inference obvious is that these committees promulgated the levels the minister who appointed them wanted set. That minister, Class, was….? Yes, Black Jack.

Any committtee member who resisted was thanked for service and dismissed. This exercise had flourished from 1949 and McEwan, while he did not invent it, brought to perfection. Then in 1961 the Liberal Country Party coalition won re-election by a single seat where a few hundred votes did make a difference, and Jim Killian made a subsequent career out of winning that seat.

Here is a paradox. That result made the support of the Country Party essential, and McEwan ratcheted up the pace of his demands on Prime Minister Robert Menzies, but it also made the voice and vote of the solidarity Liberal from the bush crucial in parliament and conspicuous in the media.

Comes the hour, comes the man. Kelly discovered his true métier. He had long written for agricultural newspapers and magazines, often about technical matters of crops and machinery. And sometimes when writing about new technology he had run up against the prohibitive cost of importing special machinery thanks to that Tariff Wall. He took to the typewriter with renewed vigour and much more detailed information and and won a national audience. He became a columnist not to be confused with the verboten C word of the era. His columns went under a few titles over the decades but ‘The Modest Member’ was the most enduring. Hence the title of the book and my several uses of the word ‘modest’ above.

When John Gorton had his brief moment as Prime Minister he put Kelly in the ministry in large part to silence him on tariffs under the rules of cabinet solidarity. Only that desire for silence could explain why this man from the interior of South Australia became Minister for the Navy. There must be a witty image here of him reversing Odysseus and carrying the anchor to the sea but I cannot grasp it.

In those days when the Royal Australian Navy wanted a new Minister a crash occurred. One night Kelly was woken by a phone call telling him the HMAS Melbourne had done it again and within a few days he got another late night telephone call to tell he was dismissed for letting that destroyer run into the ill-fated HMAS Melbourne. Back to the typewriter he went!

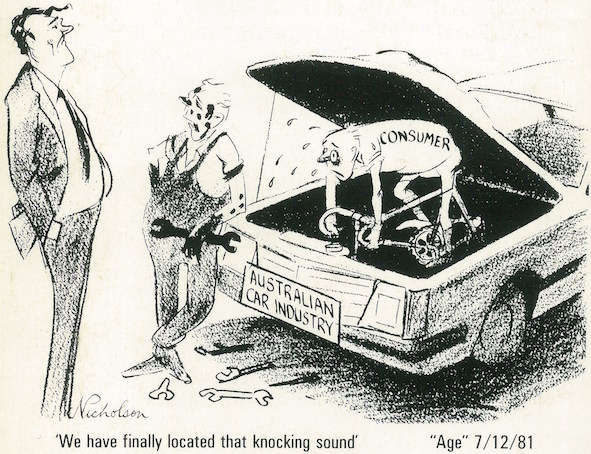

Kelly was an engaging figure, a writer with a perfect pitch for the general reader, a polemicist who argued from first principles when that was appropriate and from down to earth examples when that was the best place to start. He was no ideologue but rather he thought high, secret, and blanket tariffs held back Australia. The high, blanket, and secret tariffs were paid for by the consumer at the start, including farmers, and by would-be exporters, like farmers, in the end. Moreover, the high and ever higher tariffs encouraged sloth in both management and labour practices, affirming the historic compromise between Alfred Deakin and Billy Hughes a century ago. Kelly thought tariffs to shelter embryonic industries that otherwise would not be viable and which were vital made sense, but not five car manufacturers in a market smaller than some European cities! Such tariffs ought to be publicly justified and rationally explained, and not the product of lobbying by gift-giving agents.

Irony of ironies when the Whitlam Labor government cut tariffs by 25% one of the few voices raised in support of this revolution was the Liberal Kelly. Though many supported the move, few were brave enough to say so publicly. None of the thirty members of Whitlam’s cabinet uttered one word of support for this initiative. Kelly was one of the first of the few. One of the speeches excerpted in this book is an address he was invited to deliver to a convention of Labor economists. A generation later when the Hawke Labor government floated the Strine dollar, again he applauded. Again many Liberals agreed but kept silent. Again Labor cabinet ministers, apart from the Treasurer, kept silent.

Kelly at work.

Kelly at work.

Despite the title, this book is not a biography, more is the pity, but rather a string of excerpts from Kelly’s many publications with comments and transitions. There are asides about his early life but nothing chronological that shows the man emerging from the boy. Moreover, it jumps around in his career. We see glimpses of the man as rustic, parliamentarian, farmer, Minister, advocate but never the man whole at any stage. It is easy to read but in this respect disappointing. Tant pis.

The short Wikipedia entry on Kelly styles him a passionate free trader, something he spent years denying. in addition that entry mistakes effect for cause in saying he was ousted from the Gorton Ministry because of his opposition to tariffs. On the contrary he was put in the ministry because of disagreement on tariffs to silence him on that subject. Once sacked he was free to say his piece and he did.

He saw freer trade to be a means to cheaper consumer goods like cars, refrigerators, and footwear and the easier export of wheat and beef. Freer trade was a means to an end and not an end in itself as it is for ideologues.

Behind the Great Tariff Wall of Australia the automobiles were expensive and poor quality but many workers were employed in making them. Because of their cost and poor quality there was no export market. The same applied to refrigerators, fans, and every other manufactured product. Moreover, the Australian dollar was vastly overvalued at $US 1.47 in 1974, making agricltural exports too expensive for anyone to buy. A farmer paid high prices for tractors and could not sell any surplus overseas to earn the money to import new agricultural equipment which was over priced by the addition of the tariff. For a time the Commonwealth Government bought agricultural surpluses and distributed it as foreign aid, sometimes to places that did not need or want it, but all of this was a house of cards. Though it goes unmentioned in these pages the Oil Shock of 1973 finally blew this structure down once and for all.

Modest Kelly was but also at times mercilous. Consider Kelly’s comment on Andrew Peacock. He ‘has all the attributes I envy most: grace, charm, intelligence, and eloquence. But he gives the impression that he is waiting to be called to be Prime Minister’ and in the meanwhile he would rather not get involved in anything. Indeed.

There is in this book no account of the war years (1939-1945) except to say agriculture was an exempt occupation and Kelly stayed on the farm. But did he want to join the army at 28 and only reluctantly stay? Many men that age and older joined the army. Did he contrive to stay home? If so, how did he live that down? Later going to Canberra presented no problem to the farm. This defining hour for his generation of Australians is passed over. Gorton was a year older but served, and bore the scars thereafter.

Though later it is said a knee had been injured in youthful sports, there is nothing about that. Yet sports would have been a major social outlet for him.

And what about Lorna? She is often mentioned but we learn next to nothing about her or any children.

Colebatch is a widely published poet.

Colebatch is a widely published poet.

The book is a guide to some of the high points of his life but not a biography. To make a geologic comparison, it describes the sites but does not explain the geological forces that shaped them.

I was inspired to read this title at last (for a biography of Bert had long been on the assigned reading list) by the Australian Democracy Museum in Canberra, one of the failings of which was to give no recognition to the role and work of parliamentary backbenchers, the focus being almost entirely on prime ministers as though they governed alone. This the only ostensible biography I found.

Skip to content