A superb novel that traces the early life and career of the Spartan Gylippus of the Fifth Century BC. He was a major figure in the Peloponnesian War and the spine of the novel is derived from Thucydides’s ‘History’ of that war.

There is much insight into the inner workings of Sparta. The author knows the detail well but wears the learning lightly, though making no concessions to readers by spelling everything out. The reader is left to figure it out when Greek terms are used or to refer to the glossary at the end.

The divisions in Sparta are well realised. There are personal and clan rivalries and also personal ambition. As one character says much later to Gylippus from the outside the Spartans appear as one man. Hardly. The author makes the Spartans all too human, at times vain, myopic, venal, ambitious, resentful. But those tensions are played out behind many curtains.

Athenians are no better and their fractious conflicts are largely played out in the open air.

The contrast to Gylippus is the Athenian Nikias, another giant from the pages of Thucydides. Nikias does all in his considerable power to avoid war, and rejects command twice when it is thrust on him, and yet he dies in the war on duty,

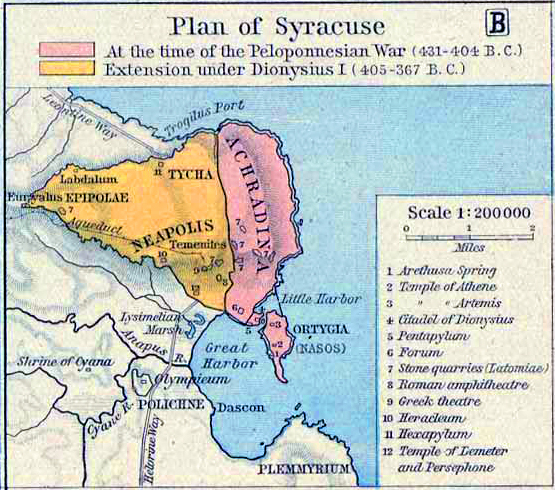

Readers of Thucydides will know that the crucible for both Gylippus and Nikias was the Athenian invasion of Sicily. The arc of the story begins with the Athenian reduction, pillage, and rape of Melos, where the cry ‘The Athenians are coming!’ anticipated the German cry ‘The Russians are coming!’ in 1945.

That was Athenian democracy at work. The opening scene of the Athenian slaughter of chained Melian prisoners and then forcing the surviving women to stack the bodies of their faheres, husbands, sons, and burn them are gruesome indeed. After that the rape begins, followed by a slave market. Two young girls escape, and though that was unlikely, as a plot device it takes them to Sicily for later events.

We went to Melos in 2007 as homage to this atrocity.

On a pretext Athens invaded Sicily to seize the island and its agricultural wealth now that the Persians have closed the Egyptian grain trade. The expedition was gigantic and command was divided and proved contradictory, aggressive in one instance, and passive in another. Nikias searched for a political solution to accommodate the appetite of the demos on the Pnyx in Athens, while the other generals wanted a battle in which to be a hero. There is no pretence at unity among the Athenians.

Melos had appealed to Sparta for help in deterring the Athenians, but Sparta did not act.

In Sicily the democratic city of Syracuse likewise appealed to Sparta, and Sparta sent one man, and that was enough. ‘Throughout time allies did not sent to Sparta for ships, or money, or soldiers, but for one man,’ said Plutarch.

The divisions within Syracuse are well realised, and full of the irony of reality. The staunch defenders of democratic Syracuse’s independence are the oligarchs, while the Syracusean democrats sell out to the invading Athenians at every opportunity. They do so not for ideological reasons but because they hate the oligarchs.

The Athenians expect a show of force will bring Syracuse to its collective knees, and are mildly surprised by the resistance, but they remain confident that Sparta will not act. Though Nikias is less confident about this than his associates. Indeed he is so very cautious that he does not want to risk a battle for the gods can be fickle and his army is a long way from home, so he set about winning local allies on the island, establishing a supply base and so on. Time passes with small skirmishes.

Then comes Gylippus. There is a marvellous scene where the Athenians are marching around the walls of Syracuse in a demonstration of shock and awe when they encounter in a field a battle-line of hoplites standing at rest. The raw Syracuseans do not stand easy. When they lined up for a battle earlier, they fidgeted, wavered, squirmed, twisted, turned, and all but ran long before the fighting started. Not so on this day. The line is firm.

The Athenian force is great and this opposing line is much less and it is near the end of the daylight. Yet these hoplites stand calm and relaxed with their shield turned side ways to the Athenians. The Athenians approach and then on command the hoplites turn the shields faces catching the last rays of the setting sun to the Athenians who then see the lambda on the shields for Laconia, or Sparta.

The shield is big enough for a man to hide behind it when the arrows fly. Together with body armour from toe to head the load on a hoplite was about thirty kilograms in battle.

The shield is big enough for a man to hide behind it when the arrows fly. Together with body armour from toe to head the load on a hoplite was about thirty kilograms in battle.

The Sparta have, this time, come, about a thousand of them face this Athenian contingent of perhaps five times that number. The frisson through the Athenian ranks is electric. Spartans! Darkness falls and no battle is joined but the news travels fast and by sunset everyone knows the Spartans have come.

Game on. Over the next three years there is much cat-and-mouse between the protagonists, each undermined by rivals there and back home. Both Nikias and Gylippus have a two-front war, one military the other is a double political one with their respective home cities and local allies.

While Gylippus did not come quite alone, he came with only a token force compared to the forty thousand in the Athenian expedition. He relied on the defensive walls of the city and concentrated on cutting Athenians supply lines and stealing silver from them so they could pay the mercenaries that comprised the bulk of their forces.

Nikias was often infirm but he was not permitted by the demos to resign and he dared not leave on his own initiative for the demos had more than one unsuccessful general put to death, sometimes along with a few relatives to drive the point home. Likewise Gylippus, frustrated as he is by his reluctant allies in Syracuse, cannot go home without a victory.

The use Hermocrates makes of the two escapees from Melos is cleverly done by the writer. The exposition of the divisions within Syracuse are well set out though the Athenian sympathisers are largely cardboard. The author leaves aside the larger question that confuses modern readers, how could democratic Athens attack democratic Syracuse. The answer is, of course, that Athens by this time would eat anything. Even as this expedition was launched there was talk of Carthage, then but a legend.

The writer’s wit, insight, sympathy for the principal characters and the way he interprets the facts recorded by Thucydides is wonderful.

Jon Martin

Jon Martin

Clearly he has walked over all the ground he describes and done so with a sponge in his mind soaking it all up. I read his ‘Shades of Artemis’ (2004) about Brasidas some years ago and found it fine, too.

Skip to content