A bildungsroman of sorts as Gully Foyle grows and changes with his experiences, and the greatest changes occur at the instruction of women. The first is the one-way telepathic black woman whom he rapes and, in a way, sets free. Later they form a team of convenience. The second is Jiz whose influence on him is considerable, making him grow and change. Finally is the White Icicle who attracts and repels him in equal measure. Least influential but last is Moira, the stay at home.

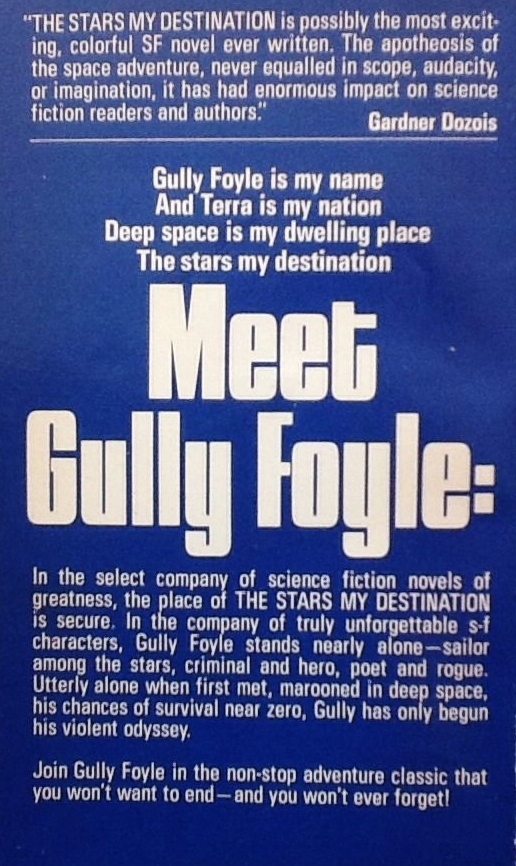

Gully begins the story as an uneducated barely verbal spaceship hand on the Nomad. Think of the channel 7Mate demographic without the drooling and scratching and you have him. By the end he is richer than all the cynics who own Channel 7Mate put together.

The Nomad is a wreck floating in space and Gully alone has survived the attack by dumb luck and a resourcefulness he did not know he had. A friendly spaceship hoves into view and he signals it, quickly and repeatedly. Yet it passes him by, contrary to all the laws, rules, norms, and ethics of spaceflight.

Thereafter he swears revenge on that ship. Driven by that desire he survives, and later prospers, and learns, and seeks the guilty ship. The adventures are many, the plot twists are deft, the characters differentiated, the settings detailed and followed through, and the science fiction is etched into the story and the characters.

The first, and as it turns out, the last key, to the narrative is that in this world of 2550 teleportation is as common as walking is today. To move from one place to another one teleports oneself, clothes included and anything one is carrying or holding. Distance varies with ability and practice. It is safer than walking since there are no crazed drivers on King Street to dodge. The method is a mental discipline developed by a Mr. Jaunte, and so it is ‘to jaunte.’ The telekinesis involved is crucial to the narrative and the denouement.

There are three treasures in this quest. First is a vast fortune of Credits 20 billion, where a hundred credits is a great deal of money. Second is a rare mineral that releases vast quantities of energy, far exceeding uranium and its mutant cousins. Third is Foyle himself, much to his own surprise, and to the reader, too.

There is much satire of the super rich, so much it grew tedious to read, but it is fitted to the overall plot like a jewel in a ring. In a world where movement is by thought conspicuous consumption to signal one’s riches becomes conspicuous transportation.

Nicely embedded in that satire is Foyle’s hiding in plain sight for a part of the time, as the most ostentatious and conspicuous transportee, while he seeks leads to the hated ship. Although his choice of an alias was a quick and certain give away it took the villains a long time to figure it out.

There are also a couple of surprising passages for a 1956 publication about the role of women in this wealthy society, sequestered, hidden, and rather like pets in a zoo. None of that applies to the first three women whom he encounters, though the last one is of that sort of society. Finally he returns to Moria as we all do. One is an illegal immigrant and the second a convict.

Without any explicit comment, Bester also shows a society with deep, very deep class divisions so that members of the working class where Foyle started, are barely educated, civilised just enough to do a job like living machines. Indeed he is so dense that at first the target for his vengeance is the spaceship itself. Only later does understand that the crew made the decision and then he targets them, but in time the realises that the captain gave the order.

There is no preaching by the author but the reader gets that point. So much Sy Fy is spoiled by childish preaching by the author using the keyboard as if it were a sledgehammer to drive points home to the dense reader all too much like the morons on Fox News yelling at the camera.

Alfred Bester

Alfred Bester

Another flaw that has stopped me reading a few Sy Fy titles is the ostentatious erudition that some author parade to show how clever they are, like the pointless CGI of so many movies, but which advances neither plot nor character. This title is free of that egomania.

That it opens with an excerpt from William Blake’s most famous poem which is integrated into both plot and character.

I read it in an adolescent Sy Fy phase but had forgotten all the details.

By the by, holding physical objects accountable for the consequences arising from them may seem absurd to us — we know the spaceship itself did nothing — but Athenians did not. A building block that fell and killed some would be tried, sentenced, and smashed.

Skip to content