IMDb meta-data is 1 hour and 22 minutes of Dali time 3.7 from 538 cinemitizens

Having just inherited the vast Stanton fortune, Scott Brady descends on the Stanton Institute for Time Research to get his watch repaired. Brandishing KPIs he demands results! The lab coats there cannot even change the battery in his Rolex! Useless! If they cannot do better he will divert the funding to Weapons of Crap Destruction and start with Hollywood!

Whoa! Under that gun the Senior Scientist skips pages in the Time Traveller’s Manual and throws all the switches. ‘More power,’ Igor, the ever present assistant, cries and more power he gets from somewhere.

They get comfy and tune in the same television I had in grad school with endless horizontal rolling and showing nothing but very old, very tired reruns on the only channel it can receive. They watch about 30 minutes of the film excerpts from public domain stock footage of rubber dinosaurs, fake cowboys, playful cavemen, decent Republicans, forbearing Christians, and other forgotten pre-Fox News relics glimpsed briefly when the horizontal roll pauses. ‘Comfy,’ well there is only one chair. Guess who occupies it? Yes, Scott Bully.

The time lab where they watch television. Note the sunken floor.

The time lab where they watch television. Note the sunken floor.

The other notable accoutrement of the lab is an elevator that descends two steps to the sunken floor of the lab. Brady makes ostentatious use of it when he comes to crack the eggheads. Later, as below, when he is running for his life, he skips the elevator and uses the steps. Makes sense, but why is it there in the first place. We’ll never know.

Well Brady is impressed that the time travel lab seems to travel in time, but where is the dollar in the past? Let’s try the future. Hmmmm, but it is his dime so Senior and Igor with the requisite female on screaming duty comply. They go looking for Yvette Mimieux and the Eloi in the future. The fraternity brothers cheered.

Whooska, and they flit through time to…. some time. There they find a spaceship and Blue Poles, yes, Slavs standing on plinths. See, it’s like this. Bully Brady, Senior Scientist, Igor, and Screamer are standing in their sparsely furnished time lab blaming each other for forgetting to order Indian takeaway before launching into the future, when the men in blue… No, wait, that is the blue men kick in the door and take them away at finger point. Thereafter the blue men, showing their superiority, climb on top of the plinths to lecture them. Well, it makes as much sense as some of the training seminars I have had.

Then in another empty room they encounter the rest of the Blue Poles who recite gibberish from the script about being in the middle of a war.

Here was Bully Brady’s chance at some technology transfer for his weapons industry. But does he take it? No, he is too busying plastering his remaining hair to his forehead to make a deal, grab a phaser, steal a super secret blue print pinned to the notice board, slip a plinth in his pocket, or anything.

Seeing how useless these travellers are, the Blue Poles send them back to the Time Shed amid a hail of sound effects. Once there levers are levered and switches switched, though what the power source would be out there is unknown to them and to us. They go whirring back to 1967 hairstyles.

But wait, Bully Brady annihilates himself. That was a nice touch, but completely incomprehensible. In short, he played chicken with himself and lost. That was one ka-boom we all cheered.

This film is proof that things can always get worse. After a run B films rated below 5.0 comes this entry. The director, writer, producer David Hewitt came to this movie after his remarkable ‘Monsters Crash the Pajama Party’ (1965) in his own search for the bottom of the barrel. This latter film has proven illusive on the inter-web but the fraternity brothers continue the search during their conscious hours.

Hewitt’s efforts are ably assisted by Scott Brady who exudes bad will with a thuggish air few could equal. He is perfectly loathsome but waiting a long time to see him get his comeuppance was boring. The direction seems to have consisted mostly of Brady turning his head to the left, and then… to the right. Wow! That’s entertainment, not. Was he rolling his brain into the socket, watching a tennis match, feeling water in the inner ear, or doing as he was directed? Decide now!

For most of the cast this is the single entry on their IMDb vitae. The fraternity brothers had no trouble predicting that.

The production values are well below Dr Who. Indeed a Dalek or two would have livened up the otherwise dead script. Moreover, the 1967 Tardis was a luxury craft compared to this Time Shed.

Month: March 2018

‘The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie’ (2009) by Alan Bradley.

A krimi with energy, wit, chemistry, zest, and pigtails. It starts and ends with our heroine Flavia de Luce bound and gagged. As if that could stop this dynamo.

It is rural England of 1950. Flavia with her older sisters Ophelia and Daphne lives with Father in the crumbling estate of Buckshaw. Ophelia and her co-conspirator Daphne delight in tormenting Flavia who reciprocates with chemistry.

Unwisely stepping into this combat zone of sibling rivalry are a pair of villains who seek postage stamps. Yes, they want to send cards home to mum with Penny Blacks!

Father came back from the war a colonel with Dogger, the handy man, and both are largely silent. Dogger had been a POW on the Burma Railroad, and he goes blank now and again. The Colonel spent four years in Changi.

Father’s wife, mother of the girls, Harriet disappeared and then died. As the story opens Father spends most of his time with stamp albums.

Flavia does chemistry upstairs in a laboratory fitted out and left by a remote forbear. Daphne reads, often aloud, from the English classics lining the decrepit shelves, and Ophelia, the oldest at 17, preens constantly in the reflections of tea spoons, mirrors, water glasses, windows. She knows who is the fairest of them all and wants to know it constantly.

Then at 4 am one morning, while waiting for an experiment to percolate, Flavia comes across a dead man in the cucumber patch! Zounds! What to do? There are many house rules against ever intruding on Father and they would likely involve capital punishment at 4 am. Dogger, then. Yes, and for a man more of less comatose he proves very practiced at dealing with the dead. Flavia reflects on the fragments she has heard about him.

Plod arrives and dismisses the ‘little girl’ Flavia with a wave. Big mistake. That sets her off on her own mission. She tries to figure it out like a problem in chemistry: identify the interactions, resolve the components, assess the intensity, and so on. She interviews neighbours ever so subtly, researches in the county library, examines parish church tombstones, walks the woods for time and distances, talks to the old school tie, climbs on roofs, and more, all with the obsessiveness only a tweenager can muster. Meanwhile Dogger confesses to shield Father who confesses to shield Dogger, and Flavia, what else is a chemist to do to buy time for maturation, confesses to shield them both.

Then there is the itinerant architectural researcher tramping about. Is he really what he seems? Or did he come from Norway? Who ate the slice of cream pie? Why was the dead bird left on the back door step? Why is the county library closed just when essential information has to be found?

This title is the first in a series, and it is a delight. The erudition spills off the page with vitality. The learning is immense but the load is light as air. Flavia’s constant resort to chemistry provides the pole star. The plotting is meticulous and integrates everything. There is nothing superfluous. Every detail dovetails into the plot like Shaker furniture joined without a nail.

The denouement does drag on, but it works a delight when comes salvation in white. Loved the convoluted chain of reasoning that Flavia developed to arrive at Norway, matched to that of Plod who found it on a clothing tag.

Alan Bradley is a Canadian with many writing credits. There seem to be nine in this series to date.

‘Leonardo’ (2017) by Walter Isaacson

An irreligious and illegitimate, left-handed vegetarian homosexual pacifist with one name and a shock of flaming red hair who dressed as dandy, seldom finished a job, and never published, that is Leonardo from Vinci (1452–1519). He would be banned by the NRA in Alabama, hung by the Veep, and not get a job at a university today.

Never hit a KPI. No tenure. No promotion. Try imagining his 360-degree review. Go on, try!

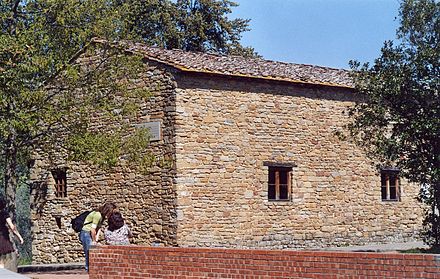

He was the illegitimate son of a notary and a servant girl. His father recognised and accepted him though for the first twelve years or so he was brought up by his mother, the servant girl, and her new husband. At about twelve Leonardo went to live in his father’s home. There is no doubt the first eleven years were formative. Read on.

His father’s house.

His father’s house.

While in the care of his mother he was free to roam unshackled by the conventions of the notary’s higher social status and rigidly conventional family life. Roam he did through hills and dales where he began the close observation of nature that never stopped. Like the boy who became Peter the Great, he was free of the inhibitions of the status that he later acquired.

His father soon realised that this boy was never going to be a notary. He was dreamy, always scratchy away at things, doodling in the dust, pulling things apart. His father arranged to apprentice him to an artist’s workshop in nearby Firenze. It was hog heaven for the lad. He did the work assigned to him, starting with crushing shells to make paint, cleaning brushes, and sweeping floors. Then he went on to preparing the surface of boards, walls, and canvases for paint. He worked his way up from these entry jobs, very quickly, to painting backgrounds like sky and hills. Next he was painting background figures which soon got him promoted to foreground figures. While a teenager his talents surpassed the master of the workshop.

Leo stayed an apprentice for longer than usual because he was content, but eventually his father staked him to set up his own workshop, and perhaps assisted in getting some early commissions for him. Leo’s talents bloomed. His only ambition was to keep puzzling away at things.

He took commissions and worked on them, in some cases for years, without finishing many of them. As he did so, he invented new techniques, the most significant being oil painting, which in turn led to his famous technique of sfumato. Together these two measures allowed him to produce colours and dimensions unlike anything previously done in tempura. Later he would stress the goal of creating the illusion of three dimensions on two. As did Ludwig von Beethoven, so Leonardo invented form and content together.

Living in bustling Firenze, Leo extended his close observation to people. He begun to carry a small notebook night and day and he sketched endlessly, as he observed. He also wrote notes and puzzles. About 7,200 half-quarto pages from these notebooks have survived that is, perhaps, a mere portion of the original total. Still this is more on paper than a contemporary biographer of Steve Jobs could find because Jobs worked in digital media from the get-go and most of it has disappeared with the passing of floppy discs, hard discs, and web sites.

Instead of finishing a commission, Leonardo would spend hours examining the condensation on a glass of cold water on a hot day, ants on a leaf, the faces of men in a pub, or applying the eighteenth coat of oil paint to a tree in the background of a painting. While he concentrated hard on what he did, he did not focus on completing tasks. All trip, no arrival.

The anonymous accusation was a common practice of the time and much emphasised in Firenze. Write out an accusation and drop in the box. Done. (This was a practice revived by the Naziis in Occupied France.) These accusations covered everything from tax dodging, to cheating business partners or customers, short changing deliveries, adultery, and homosexuality. While sodomy was a moral sin and a capital crime, it was also much practised in Firenze. Hypocrisy is not confined to D.C.

One such latter accusation was made against Leo but it was unsubstantiated upon investigation and he saw it off. Other similar accusations, however, followed. Whether any specifics in the assertions were so, it is true that he preferred boys to girls or women. True or not, sustained or not, the accusations and innuendoes were making his life and work difficult. After he left Florence, nothing more is heard of such accusations, though it is clear that was his way of life.

In Milan the usurper Il Moro, was buying legitimacy by attracting entertainers like Sharon Stone to Milan. To make peace with the new ruler of Milan, the Signoria of Firenze commissioned Leo to make a lyre of silver for Il Moro and personally to deliver it. While so doing, Leo also applied for a job as engineer, maestro, painter, and celebrity pet. The duke commissioned him to do a giant equestrian statue which of course remained unfinished during the seventeen years Leo spent on Moro’s dime.

He did earn his keep by producing entertainments for the duke. These shows included automatons, flying hoists, tableaux, and all manner of smoke and mirrors. The author makes the point that with these shows, Leo had to deliver on time, on target, and on budget. And he did! Repeatedly.

Being an impresario distracted him from the equestrian bronze but made a great reputation for the duke. (Later this duke would invite the French to come to his aid and that precipitated more than thirty years of incessant war in the Italian peninsula. The French liked shopping in Italy, and paid with swords, crossbows, siege guns, cavalry, and more.)

In these shows Leo’s engineering and artistry were united. They also demonstrated his management ability to prepare and stage them. He spent years in Milan and only left when Il Moro’s world collapsed. He returned to Florence briefly and then in a dream come true King Francis I of France offered him a pension, not a commission for a specific work or works, but retainer to do what he liked.

He set up a house and pottered away.

While he had been a strapping red head in his prime, he aged rapidly and badly. Those who met him for the first time in his fifties and later routinely took him to be ten or more years older than he was.

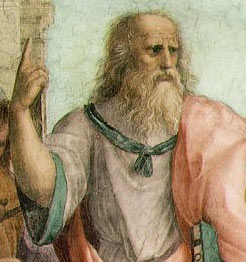

There is some reason to believe that Raphael used him as the model for Plato, as above, in his great painting of the Academy for a Pope.

Most of Leonardo’s engineering ideas were never tried, and he completed few paintings, yet he was recognised far and wide as the genius of the age. How does he compare to Paris Hilton, that is a question to consider. His recognition infuriated toiling rivals like the religious zealot Michaelangelo who tried to blacken Leo’s name at any opportunity.

To commission a work from Leonardo was difficult and almost always fruitless. He often played hard to get and declined commissions. When he accepted, whatever the notarised contact said, it was done in his way and on his terms. That most famous of all paintings, the Mona Lisa, which the author details at length was never finished. While Signor Giaconda commissioned it, he never saw the completed work. Instead like several other paintings Leo carted it from Milan, to Florence, to Rome, to France, daubing at it off and on for years.

It was not procrastination. His technique took time. In Lisa’s case, the canvas had a base of white lead, which even with other coats of paint over it still reflects light like nothing else. The lead coating took time, and by the way, this unique property of white lead paint was recognised by others and commonly used on the eyes of portraits. An artist who licked his brush to get a point with this lead for the white of eye developed lead poisoning and this killed many.

Over the white lead Leonardo added very thin coat of oil paint and then waited weeks or months for it to dry. Then another with a wait. And so on. At times he changed his mind and altered a painting and waited. He out waited all of his patrons except Francis who had hired him as a companion more than anything else and they seemed to enjoy each others company. When Francis had time off from murdering Protestants or sacking Italy, he visited Leo for a natter. Though I did wonder, without enlightenment, what language they spoke together.

Leonardo was never idle and in the weeks of waiting for paint to dry he would take up a new project and do, say, a series of drawings of water falls, or rivers. He was always fascinated by the motion of water. Indeed at times he speculated that water to the Earth was as blood to the body, and he meant that literally as much as figuratively. Though for all his polymath genius he never understood the fifth grade science of evaporation.

While he learned much from reading, he never published his own research, though he spoke of doing so, but those words became another unfinished project. He had been an autodidact in his early years and had so little education he could barely read, and he was defensive about that for years. More or less secretly he spent years trying, off and on, to learn Latin with little success. (Miss Vera Earl, MA, would have put his declension in order in no time!) Gradually he came to read Italian and learned from the tomes he read. Perhaps there was a psychological barrier to publishing because of his early life in which books were for others.

It is a wonder, in an age without knowledge of germs, he lived as long as he did. That the white lead did not kill him may be down to his slow pace of painting. But also, where local circumstances were conducive, he did hundreds of autopsies with accompanying drawings of the muscles and bones of the human body without much hand washing, sterilising of knives, and such. Since most of the cadavers he could work on came from the poorest strata of society, often they were diseased and infested, yet he lived.

This quintessential embodiment of the Italian Renaissance, this son of Firenze, this Tuscan-speaking Italian died in France and King Francis gathered his mortal possessions, so that in time the Mona Lisa and many of the drawings passed to the Louvre, where I once saw Lisa behind a bullet proof glass and over the heads of and in the storm of flash bulbs from hundreds of Japanese tourists. I also saw for a few seconds two of his completed, smaller religious works in the Hermitage in a squeeze play.

Isaacson has a prosaic explanation for Leonardo’s (in)famous mirror writing, which is best read in its entirety. It demystifies this practice, and disqualifies Leonardo from the Rosicrucian Hall of Fame.

He was a contemporary of Niccolò Machiavelli, who signed for the city of Florence a contract commissioning Leo to paint a triumphal scene. Needless to say it was never completed. Isaacson supposes Machia and Leo were friends, but I rather doubt it. The evidence is circumstantial at best, and as personalities they had nothing in common. Geniuses do not always attract each other.

Still Isaacson’s book is extensively researched, measured in its inferences, and concentrates almost always on available evidence, which is almost always art, paintings, sketches, models, and drawings, much of it from the notebooks Leo always carried. He succeeds in bringing alive this man who could spend hours examining the condensation on a glass of cold water, drawing the shapes as they came and went, or simply staring intently at the glass as if it alone existed in the world.

The notebooks were numerous and many have been lost. Some were sold off to admirers on his death, and so valuable was anything of his that some notebooks were ripped up and the pages sold separately. In this practice was room for forgeries. Yet much of them remains and they are the only autobiographical source for this remarkable man. On the pages are his many interests, and lists of things he wanted to do, find, understand, know, and test. By the way, though he was pragmatic enough to keep it to himself one entry in the notebooks says that ‘the sun does not move.’

He was so remarkable that even in his lifetime apocryphal stories of his powers were circulated and these multiplied after his death. The journalist of the time, as now, were completely unscrupulous in the exaggerations heaped upon his name to peddle their wares. Thus he became encrusted with myth and legend. Part of Isaacson’s achievement has been to strip away those layers that readers may see the man within.

‘Even the Dead’ (2017) by Benjamin Black

Dublin in the early 1950s is a world unto itself turned inward. Dr Quirke is a pathologist who observes much and suspects more. When a road accident victim’s corpse is examined he finds a contusion on the temple that is inconsistent with the car crash. Musing follows. In time, he mentions his doubts to the Inspector Hackett of the Serious Crimes Squad who noses around and finds unpleasant emanations. This is the seventh entry in a series and it is tired, but perhaps complacent is the right word: ‘If I write it, the reviewers will praise it.’ He did and they did.

Though the spring weather is benign, the choking conformity of Maxima Catholic Dublin is inescapable. All in Dublin is more Catholic than the Pope. It is certainly more Catholic than the Rome of the time. The Bishop’s Palace is the seat of power in Dublin, not Tithe an Rialtais, the large Edwardian building enclosing a quadrangle on Merrion Street wherein dwells the Taoiseach by which we once walked.

There is only one escape permitted from this suffocating pall and that is alcohol. Frequently in Quirke stories, and no doubt in 1950s Dublin life, the pregnancy of unmarried women is paramount. Moreover, every thread, however long and ravelled, eventually traces back to the Catholic Church and its baleful tentacles.

These books are very well written and the picture of Irish life seen through Quirke’s eyes is to travel back in time. Yet in these books there is precious little detection, no police procedure despite Hackett’s occasional plod, and no mystery. Much is also predictable, as Quirke’s sexual conquests. As soon as a women is introduced into the story, we know she will soon succumb to his charms.

Instead we have Quirke, holder of a prestigious and authoritative position, a highly trained and accomplished medical doctor, a widower, father of a bright grown daughter, comfortable of income, handsome and attractive to women, who spends nearly every minute feeling sorry for himself in a self-imposed melancholia where he wallows for pages and pages, smoking cigarette after cigarette, drinking drink after drink. Evidently his pathologies did not involve lungs or livers.

Instead of detection we have meals, drinks, cigarettes, meals, drinks, cigarettes, meals….. On it goes. Yes, the prose is polished and the observations of life’s details exact, but repetitive and inert. There seems to be neither point nor purpose to the the prose. Some of the characterisations are profound, like Quirke’s terminally ill brother but have no place in the plot.

There is no doubt John Banville, Benjamin Black’s after ego, can write. The portrait of the victim’s father is striking and sympathetic. The contrast, however, is the government official whom Hackett interviews, who is little more than a cartoon character, flustered by the simplest question. Banville has respect for the father and none for government officials and it shows as he makes up the reader’s mind. Take that all those who work for the government, including those who uphold the intellectual property and copyright laws that secure Banville’s income. all those who regulate and maintain the internet services that provide a platform for his novels, all those who police crime and who had to deal with IRA on the border for a generation, all those who make difficult decisions about troop deployments on UN Peace Keeping missions, these are all clots!

I also found the reference to the Spanish Civil War confusing. The International Brigades were certainly there but the specifics mentioned in the story did not compute.

‘Men into Space’ (1959-1960)

IMDb metadata: run time per episode in 26 minutes, rated 8.1 by a paltry 122 cinemitizens.

A one-year television series in thirty-eight episodes from the United States depicting space flight pioneering with respectful attention paid to the science and technology. Willy Ley would have approved. Maybe he did. It stars everyman William Lundigan.

And he alone is the constant through the episodes. No other player is listed for more than eight outings. That may partly explain its failure, not enough characters to develop audience identifications, together with the lack of dramatics from calm, cool, collected, and sometimes nearly catatonic Bill. The tone is realistic and the presentation emphasises the difficulties. Space flight is hard enough without zombies, meteors, or John Carradine.

The drama emerges from the divergences among the crew, and occasionally from mechanical elements. Some of the crew are determined to complete the mission even at high risk, and others are more cautious. Everything is being done for the first time, and some of the equipment fails. Think Apollo 13. Think low-bid contractors.

The series was made with what appears to be the unstinting cooperation of the USAF, as noted in the terminal screen acknowledgements. These Saturn rockets are military without a doubt.

In 1958 President Dwight Eisenhower created NASA to explore space. There must be quite a story there of Ike wresting some of the missiles from the generals. But who mistrusts generals more than a one-time general, and who better to convince Congress likewise than that same general.

No doubt this creation was part of a policy to encourage the Soviets not to use space for military purposes. But of course there must have been some serious cooperation between NASA and USAF that continues today. Those rockets grow on money trees in the defence budget green house. No doubt there have been occasions when the USAF made a bid to take over from NASA, too. These bureaucratic fights would be fascinating studies in themselves.

This series might have appealed to the Air Force as publicity for its sole-agent claims to space. Though the references to an enemy ‘them’ are few. Indeed in one episode the safe return of Bill himself is only possible with the cooperation of a Russian tracking station. No doubt when the script writers get bored they will throw in some sabotage, and that friend of the jaded writer, the meteor, but not in the early going.

Even so it is notable that each of three episodes seen so far end in failure. The Moon orbit is aborted and the whole crew returns safely. The Moon landing is compromised and one crewman dies on the Moon, and the rest have to leave before completing the mission. Ditto the third, another injury truncates the it. The program, a cynic might say, was creating a climate of low expectations for space exploration.

Man down!

Man down!

The key is so low that the first steps on the Moon are nothing much. The door opens, down the ladder they go and start standing around waiting for the director to cue them. No dramatic pause before the step onto the surface. No finely calibrated remark. No excitement.

No speeches and no flag. Neil Armstrong got no tips from this scene for his step into eternity.

While there is a revolving door of characters the sets are of great verisimilitude for the day, thanks no doubt to the Air Force. The acting is fine, the more so considering how quickly each episode was made. Maybe not in one-take, but close to it. The worried wives, look very worried. The anxious generals on the ground look anxious. The stressed flyboys look stressed. By the way, the ubiquitous Australian Michael Pate appears in one episode.

The one mistake is in the portrayal of the representatives of the media of the day as sober, sensible, and civil, but then maybe they were back in those days. Certainly today no self-disrespecting ABC journalist would fail to badger the worried wives with questions about death, children about absent fathers, generals about incompetence, and so on. Why let the dust settle when stirring it up goes on the resumé.

Like the acting and realism, the special effects with models and travelling matte are far superior to many a B-movie reviewed on this blog. Free-fall in the cabin is fun to watch. In space there is no flame from the rockets. The EVA astronauts are floating in the ether.

The Mind Palace has no entry for this program from the time. It was programmed against ‘The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet Nelson’ and ‘The Price is Right,’ so I guess our boob tube was on the Nelsons in 1959-1960.

‘Escape from Galaxy 3’ (1981)

IMDb metadata is this: 1 hour and 32 minutes of treacle, rated 3.2 by 277 cinemitizens who confessed to seeing it.

First there was ‘Starcrash.’ and then when it seemed Italian Sy Fy films could not get worse, the same production crew that made it came out with ‘Escape from Galaxy 3,’ from which there is no escape. The production liberally plagiarised the special effects, vista shots, and costumes from the earlier film, and this story, such as it is, starts where ‘Starcrash’ (mercifully) ended.

What is the set up? Princess Lolo and King Dad are in for trouble when Liberace shows up dressed for the Newtown Mardi Gras right down to sparkle in his beard.

Looks like he fell off a float.

Looks like he fell off a float.

He has cosmic mega candelabras and blasts them. He did not come in peace. He came in sparkle. Since he is styled ‘King of the Night,’ the fraternity brothers wondered if he was searching for the Queen of Night from Mozart with her very, very high Cs. Should be able to hear her anywhere in the galaxy when she hits it.

Yes, this is yet another Italian Star Wars exploitation. It goes to the bottom of a long list.

Lolo with Seia, her bodyguard, flee. Liberace pursues. They flee some more. Liberace pursues some more. When he gets close they fire their puny candlesticks and he replies with his cosmic mega candelabras that destroy whole planets that get in the line of fire. This takes forty-five minutes or five on Very Fast Forward, best friend of the obsessive film reviewer.

Desperate for an espresso, Lolo and Seia land on Earth, 20,000 years ago to tank up. Yep. the fraternity brothers recognised the Italian peninsula for what it is, a phallic symbol. So do the travellers. Once there they learn from the birds and bees. This couple of losers did not know what those bits were for back home. Now Seia takes his duties as Lolo’s body guard to new…. No wonder Liberace thought it was time to exterminate them. There follows about forty-five or five minutes of frolicking. Old Liberace has been forgotten. Oh, sure.

Until he arrives with his mega cosmic candelabra and starts blasting Earth, then the script remembers him. The natives blame Lolo and Seia for making God mad at them, and so they should. A soccer riot follows and Liberace grabs Lolo and Seia, though why he wanted these two stick figures is not clear. They face off, and — whoa! — Seia burns Liberace to a crispy critter with his laser eyes. ‘Laser eyes?’ Yep. Saved those for the end.

Lolo and Seia decide to stay on Earth and start Italy.

The end.

In a word: terrible.

The Italian title makes it sound far better than it is, namely, ‘Giochi erotici nella terza galassia,’ which according to Siri translates as ‘Erotic games from the third galaxy.’ There is no science and the fiction is incoherent, bland, and predictable (except for those laser eyes, which he must have borrowed from Superman and augmented them somehow).

It was also released in English-speaking markets as ‘Starcrash II’ to warn off movie goers. It worked. Other Italian imitations of ‘Star Wars’ include the aforementioned and difficult to forget ‘Star Crash’ (1978), ’Star Odyssey’ (1979), ’War of the Planets’ (1977),’ ‘The Humanoid’ (1979), and others I have successfully forgotten.

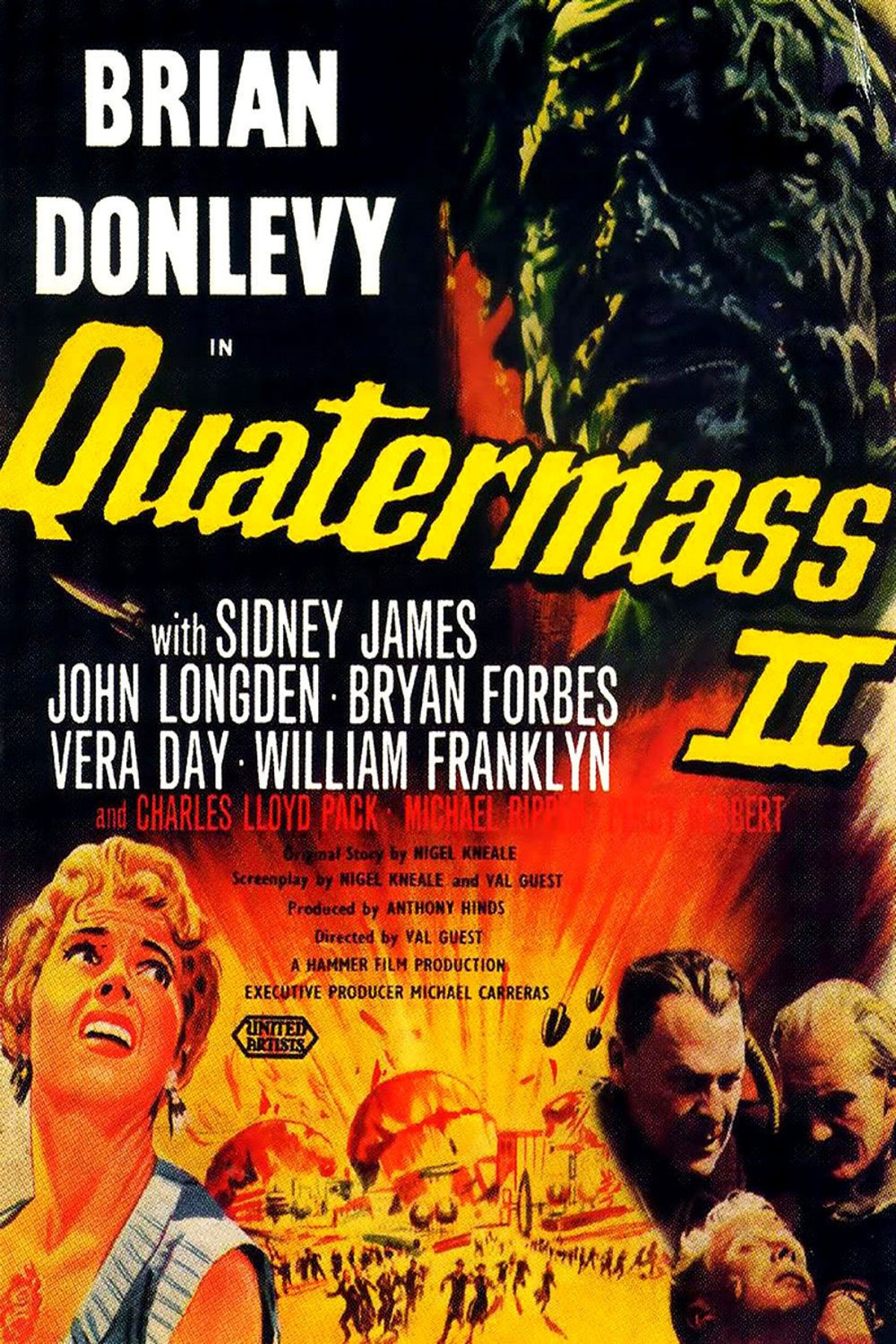

Quatermass 2 or II: Enemy from Space’ (1957)

IMDb metadata is 1 hour a 25 minutes, rated 7.0 by 2773 cinemitizens.

When Quatermass’s moon project is starved of funds, he goes to Whitehall to bludgeon bureaucrats into stumping up the dosh. This method has always worked before so off he goes. Meanwhile, his crew watch the gentle ascent of a flock of meteors.

Strangely in London no one this time is moved by Quatermass’s bluster and bullying. Quatermass draws the only conclusion possible, eh Erich. Yep, the aliens are at it. That, by the way, would explain a lot about Whitehall decision-making over the years.

After shouting at his subordinates for a while, Prof Q pays attention to the meteors, and now having nothing better to do, he scouts the location where they fell. Well, no, he cannot do that because it is fenced off in the manner of a German death camp. Moreover, the perimeter is patrolled by some very silent, icy, and heavily armed guards in get-up that is un-English.

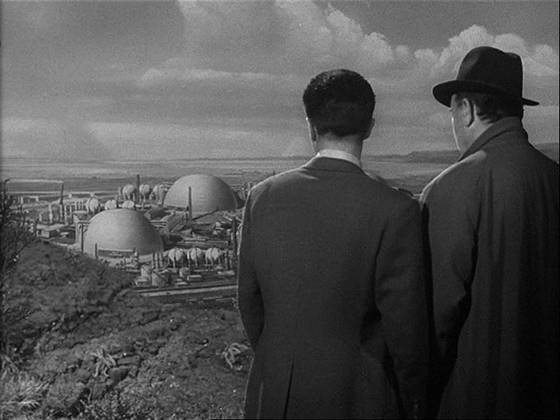

A conveniently located viewing platform offers perspective to the Prof.

A conveniently located viewing platform offers perspective to the Prof.

These guards spirit away the hapless assistant who drove Quatermass to the locale, and as Quatermass goes all Alpha Male on them, one steps forward and hits him with the butt of a gun. Down went Prof Q to the cheers of the fraternity brothers. ‘About time someone told him where to get off for assigning all that homework over Easter,’ they cried! Aside: all profs look alike to the fraternity brothers.

The meteors are eggs that hatch out a gas that infects humans, turning them into slaves. The word ‘zombies’ is used once, but oddly not the word ‘Republicans.’ The slaves built in a day or two the great complex Quatermass espied before his lights went out. When he recovers he rushes about, partly to find his assistant who has the keys to the WC, and to divert funding from this mystery project back to his own KPIs.

More doors are slammed in his face. Ah ha! It is a vast conspiracy. Yep the ‘Invaders’ (1967) have been at it a decade before Roy Thinnes came along, and most positions of authority are occupied by Republicans aka aliens! Look at those little fingers! Proof positive!

There is a fabulous scene where a delegation is being shown around the facility and a parliamentarian wonders off and is slimmed! Slimmed! There are many striking touches like this in the film. But consider what does it take to slime a politico.

Sid James appears as a sotten journalist who telephones in the story from the local pub, only to be mowed down by the aforementioned security guards. Witnessing this murder, shakes up the locals and to calm down they watch ‘Frankenstein’ (1931) and get an idea. They gather with torches, pitchforks, straw hats, darts, and other accoutrements of rural life to march on the mystery site.

Mayhem ensues around a Shell Oil refinery. Quatermass just happens to arrive to boss everyone around. Meanwhile, his deputy, Bryan Forbes, launches the rocket and somehow this disconcerts the alien protoplasm. Forbes went behind the camera to direct later in his career.

The protoplasm which looks like that of the earlier ‘Quatermass Experiment.’ He needs an autoclave in his laboratory to clean up and prevent such growths.

The protoplasm which looks like that of the earlier ‘Quatermass Experiment.’ He needs an autoclave in his laboratory to clean up and prevent such growths.

At no time does Q try to negotiate with the amoebas. A big BOOM follows. Catastrophe averted, yes, but Quartermass strides off to prepare for the next one.

The Quatermass Franchise grew from Nigel Kneale’s typewriter first as serials on the BBC and then films. He was a very fine writer, some of whose other works are reviewed elsewhere on this blog. This script was filmed as a television series but it did not survive the BBC policy of taping over past productions. The director was Val Guest, who once again offers a masterclass in pace.

This outing presages much to follow in its paranoia, the mark of Cain on the humans who have succumbed to the aliens, the James Bond shoot out in the refinery, but also draws on the established tropes with those meteors. The obvious compareson is ‘Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ (1956) which stole much of this film’s thunder in the North American market.

Scuttlebutt on the interweb street says Kneale and Guest argued about the character of Prof Q. Kneale wanted an avuncular English eccentric, but Guest wanted energy and tension in the part, and the producer wanted to sell the finished movie to the American market, so he wanted an American in the lead. Some of the more inane remarks, and that is a competitive field, on the IMDb blame Brian Donlevy, who played Quatermass, for the characterization, but it is obvious to anyone but a retard that the director did it. I guess the blunt, belligerent, brash, bossy, bullying, boorish, and bellicose Professor Quatermass was their idea of an American after having studied Dwight Eisenhower.

‘Mesa of Lost Women’ (1953)

The IMDb metadata is 1 hour and 10 minutes of Dali time, rated 2.5 by 1099 cinemitizens.

In the middle of El Muerte desert in Old Mexico Uncle Fester is conducting experiments to recreate Gale Sondergaard! ‘No chance,’ said the fraternity brothers, ‘she was one-off.’ Fester is splicing genes from an unlimited supply of spiders and an unlimited supply of Hollywood wanna-be starlets. The result was Tandra Quinn aka Tarantella! There were many others such women with Fester but only she had a name in the cast list. The others are termed, with admirable imagination, ‘Lost Woman.’ About ten of them. They were not even distinguished by a number like Lost Woman 1. The fraternity brothers hoped to find them when the lights came on.

Two bumps upset Fester’s apple cart laboratory. First he awarded a nationally competitive research grant to a scientist to join his lab. Fine. When this aged Post Doc shows up, turns out, he doesn’t like this kind of gene splicing. What a sissy! He even recoils from the fifty-pound spider Fester keeps as a pet, an early experiment that did not work out quite right.

Second, an airplane crash lands on the mesa and brings onto the Rock of Otranto a mixed group of passengers and crew. They blunder around. Smoke cigarettes. Blame each other for the crash. Decry Republicans. And notice, slowly, that their number is being diminished.

Fester has sent his little men after the intruders. ‘Little men?’ Yes, a by product of splicing the spider women is the production of shrunken dwarfs as their paramours and ….. [Here the veil is drawn.]

The film was a boon for Hollywood’s dwarf population some of whom got a day’s work out of it. Likewise for the wanna-be starlets. Neither dwarf nor starlet had any lines. These human spiders, as Fester likes to call them, communicate by telepathy. Ergo, the actor’s minimum wage did not have to be paid.

This set-up has at least as much potential as ‘The Wild Women of Wongo,’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog, but the execution undermines any prospects it might have had. Though admittedly it is better than that film but then so is a blank screen.

It is told as a flashback within a flashback and the characters are undifferentiated so that the audience — me — was never quite sure who was whom, apart from Fester. The oil man who finds the couple wandering in the El Muete desert and the airplane pilot were identical twins on camera, but in the credits different guys. Oh.

Though the second scientist escapes from Fester’s Mesa later he just happens to the on the airplane that crashes on to the mesa. How easy is the scriptwriter’s life with such coincidences.

Equally coincidental Fester’s oriental servant is one of one of the passengers on that plane, though he is not a dwarf. How he got from the laboratory in one scene to sitting on the airplane in the next is down to the magic of the scriptwriter’s typewriter.

Within minutes of leaving the wrecked plane the just married bride among the passengers leaves her husband and goes into the bushes with the pilot for a anatomy lesson. She wants him to understand her. He does.

That second scientist, when he fled put miles between himself and the mesa, yet by coincidence he found Tarantella in the bar he walked into for a drink. After he shot her dead, she got up and left. Spider women never die! He then boarded the airplane to….the Mesa of Lost Time.

Yet later they all die in a fire started by our hero, whoever that was.

Throughout the mish-mash are interspersed for no discernible reason close-ups of Fester, perhaps he is using You Telepathy Tube, but who knows. There are also a number of equally pointless close up of the wanna-be’s larded into the proceedings. The fraternity brothers will explain those transactions to anyone who writes in and asks nicely. The dwarfs don’t get many close-ups.

There is an intrusive musical score that sets teeth on edge. It consists of three chords on a guitar repeated without purpose or end, punctuated now and then by a vase falling on a piano keyboard. Half-way through the fraternity brothers formed a lynch mob and set out to find the composer.

The direction is haphazard, if existent. The production values came fo Filene’s Basement. Fester is too low key to laugh at. Most of the cast are described on the IMDb with this phrase, ‘little remembered.’ Yep. For most of them this film was the apex of their career.

This movie is another example, among many, of the overlap of the genres science fiction and horror. There is ostensibly science in Fester’s lab explained with dialogue, but the results are horrible. Well not so horrible as to require expensive make up and costly special effects. Though, admittedly, the finger nails take seeing.

‘12 to the Moon’ (1960)

Internet Movie Data base metadata: 1 hour and 15 minutes in Dali time, rated 2.8 from 819 cinemitizens.

The International Space Organisation represented by silent film star Francis X. Bushman (born in 1883) proclaims ‘the greatest day in human history’ with the launch of the ISO ship and crew for the Moon! ‘All nations have contributed’ to this ‘Earth shattering event,’ he says. FXB has other Sy Fy from this era on his CV.

The twelve are diverse, including two women, who are not demeaned or deprecated, as is so common Sy Fy of this era and ilk. They go about their business without sneering by any of the men, or — what is always worse — efforts at comic relief at their expense.

The security is tight. Each crew member has to say his or her name! Wow! That would stop the fraternity brothers most days of the week, without a peek at the driver’s license.

We have a Frenchie, a Germanian, a Brit, a Jap, a Swede, a something else, a Nigerian, an other, and a Pole resident in Israel, and a Russkie. This Russkie is played by someone born in Russia, namely the Saint cum Falcon, showing the wear and tear of the bottle. The leader of the pack is Yankee Doodle.

Smooth sailing does not last long. Members of this handpicked crew soon fall to bickering among themselves, per the script, and then they have to duck meteors, the scriptwriter’s friends. Whew! Still they make it to the Moon, where their number quickly diminishes. I seem to recall one of them falls down a hole. Gone. Two others wander off. Gone. Another gets clonked by a blunt meteor. The crew is getting less international by the minute.

Then from the ship’s computer comes a string of meaningless characters, which Yankee Doodle immediately recognises as Moonshine. Ooops, just kidding. He says they look Oriental and since one Oriental looks like another he orders the Jap to translate. Being a smart fortune cookie she quickly learns this Moonie lingo and translates. The message is: ‘Scram! But leave the cats.’

Cats? Yes, they brought two cats for scientific reasons which are too delicate to reveal on a family blog. (They also brought a cocker-spaniel to sniff their luggage.) Evidently the ‘Cat-Women of the Moon’ (1953) wanted company. (This gem is reviewed elsewhere on this blog.)

We never see or hear the Moonies, hiding as they are deep underground to save on the production budget. As if! Maybe this is a trick to ruin the mission by one of the crew, shouts the hysterical genius. He is slapped down with his own slide-rule. But it turns out, in a twist, that the Frenchie is trying to scuttle the mission because he is one of ‘them,’ though the Russkie is not. Those who figure this out get a giant No-Prize. The geriatric Russkie is no match for the geriatric Frenchie, and Yankee Doodle has to whack him.

They lam off the Moon only to find the Earth a snowball. Yes, the Moonies want to watch ‘Ice Age’ (2002), not reviewed anywhere on this blog. What will Twelve Minus do? Of courses, blow it up! Huh?

They resolve to build an atomic bomb, fly over a handy volcano, drop the bomb down the spout, and the explosion will restart the carburettor, or something. This is a risky mission so the two who are to do it are bitter enemies, who have a reconciliation just before they ride the bomb down, like Slim Pickens. (You either get it, or you don’t.) Two more gone to dust.

That fixes that. Twelve went away and seven came back. I lost count, as did the director.

The end.

This a work of fiction without the science. The absence of anything remotely resembling scientific knowledge is complete. The ship exhaust flames in the void of space. The cats breathe on the airless Moon’s surface. The gravity is one-sixth so that of Earth, some characters trudge along as though under the sea. When the explosion in the volcano occurs we get shots of solar flares. Though they are always putting on and taking off crash helmets, there is no glass in the front of the faces because it is unnecessary thanks to hocus pocus. The list goes on. Since the film presents itself as a near documentary account such errors are laughable.

But even more amusing than these mistakes is the apologies for them in some of the User Reviews on the IMDb. Usually I skip these comments because so many of them are egotistical drivel, but since few of the critics linked to the IMDb, and none of the ones I have learned to respect, comment on this sludge I scanned the User Reviews. It was a refresher course in why I do not do this. Several scored it as 10 because of the gripping story. Oh hum. A couple of others praised its scientific acumen. No doubt a climate change denier. ‘Stop!’ I cried, and I did — stop.

Then there is the stage craft. In space we see the black pole on which the spaceship is stuck as it passes in front of the star matte. In the first shot of the Moonscape there is someone walking in front the light casting a shadow on the distant cliff face. Boom mikes occasionally intrude at the top of the screen. The actors sometimes speak so slowly it is clear they are repeating lines just recited to them.

It is also a creature feature that spares the expense of having a creature. We never see the Moonies, though the fraternity brothers suspected the Cat-Women were the culprits.

All in all though it is a crowded field, it is a contender for the worst of Sy Fy.

‘Revolt of the Zombies’ (1936)

IMDb metadata: 1 hour and 5 minutes, but it seemed longer, rated 3.2 by 1241 cinemitizens.

The set-up is complicated for such a short pot-boiler, but here it is. During the Great War a French Army is being overrun by Huns, when….a regiment of Colonial Troops from Cambodia appears and proves impervious to German steel and lead. France is saved! A dead soldier cannot be again killed, and these are zombies, the animated dead.

They were raised from the dead for just such an emergency by a Cambodian priest who parades around the winter trenches in a loincloth.

In a show of gratitude the priest is murdered because such zombies could mean ‘the extinction of the white race,’ cries one general to another.

While Woodrow Wilson was re-drawing maps at Versailles, these generals convene an international meeting for the purpose of eradicating the zombie threat to ‘the white race.’ Managers are keen to do this since it is a waste of ammunition trying to kill the dead. The plan is for an International Expedition disguised as archeologists to find the heart of Zombiedom at Ankgor Wat and kaboom it. A few back projections from a real expeditions suffices to set the scene.

Indiana Jones was too young to get a visa so instead they have assembled Dean Jagger with hair, Frail, and Beau among others. The latter two are as one whenever possible and a few times when it seemed impossible, according to the expert opinion of the fraternity brothers. Yet Dean professes his love for Frail, who is kind to him, always a bad sign, kindness like that. He does not take it well.

By now Dean, since he cannot be one with Frail, has been swotting the books and has discovered the secret incantation that saps everyone of their will — McKinsey Speak! The mumbo-jumbo of Key Performance Indicators, 360 degree reviews, deliverables, and the living dead are conjured, as can be seen in any meeting room nearby.

There in front of the back projection Dean has his way! The fraternity brothers took copious notes.

But Frail still does not love him! There is no money back guarantee with McKinsey-Speak so Dean falls for the oldest trick in Eve’s book. He renounces his mystic powers so that Frail will love him for what he is: A dope.

Even as the pompous Dean does on about what a noble thing he is doing, relinquishing his supernatural powers, all for Frail, those Cambodian zombies in the back projection revolt against his will-sapping tyranny. End of Dean, hair and all.

The end.

Good thing Woodrow was busy with the crayons, because if he had got wind of any of this plan, he would have banged on about applying the Fourteen Points to zombies. (Woody never knew when to quit.)

However, the scriptwriter would have done well to borrow a map from Woody since this scenario starts in a battle along ‘the Franco-Austrian frontier.’ Huh! No such place. The Austro-Hungarian Empire of the Great War was a vast conglomeration in central and southern Europe a long way from France.

The border between science fiction and horror is permeable and one genre informs and influences the other. Thus it happens that horror movies like the one at hand turn up in searches for Sy Fy. Seeing it on a list one night, I chose it because the length suited the nocturnal schedule. I watched a very poor print on You Tube, though subsequent investigations found a better one at the Internet Archive.

The commentariat has a lot to say about this film, despite its well-deserved obscurity. It attracts attention because by some measures it is the second zombie film to come from the Dream Factory. The first was ‘White Zombie’ (1932), reviewed elsewhere on this blog, which was a commercial and critical success. No wonder: it starred Bela Lugosi. ‘Revolt of the Zombies’ came from the same production crew in the effort to recapture the magic and the money, and recycles some scenes from the earlier film, but lacks the verve, plot, and — most of all — Lugosi. These two films gestated a plethora of subsequent zombie movies and in time the concept of the zombie evolved to meet the needs of scriptwriters.

‘The concept of the zombie’ is something, along with much else, to which the fraternity brothers have heretofore given no thought. That time is over.

A zombie is a corpse raised from the dead and animated but without human qualities, like greed, emotion, hate, stupidity, and the other loveable features of our kind. They are directed by the mind of another, like robots. Indeed the word ‘robots’ is used in ‘Revolt of the Zombies’ about the Cambodian zombies in the trenches. That is per the ‘Oxford English Dictionary,’ which finds the word ‘zombie’ used in English in 1819 by a traveller returned from Brazil who observed Voodoo rituals.

Wikipedia assures the gentle reader that zombies play no part in ‘the formal practice of Voodoo.’ ‘The formal practice of Voodoo,’ that wording set the fraternity brothers to wondering about the informal practices. Or is Voodoo just about dolls and pins? (Is this the place to confess my own flirtation with a doll and pins?)

It is absolutely obvious that the Cambodians whom Dean enthrals are alive, and have not yet ever been dead, ergo proclaims the commentariat they are NOT zombies. Tricky. They have no wills and are mentally enslaved, but they have yet to be dead so how can they be undead. This circle goes around and around.

‘The living dead march again’ screams this lobby card yet the movie belies it. Moral? Never trust a lobby card.

‘The living dead march again’ screams this lobby card yet the movie belies it. Moral? Never trust a lobby card.

In the spate of zombie films that followed, especially in the 1940s when horror films diverted audiences from the real horror of the Great War II, the zombie mutated to become a flesh eater. Nor was it any longer necessary to die first before dining on the flesh of others. Zombieism became virus passed by touch or bite, taking a tip from Dracula, a nip. In the Cold War, the soulless Zombie got red.

For further details see….‘I Walked with a Zombie’ (1943), ‘Revenge of the Zombies’ (1943), ‘Zombies on Broadway’ (1945), ‘Valley of the Zombies’ (1946), ‘King of the Zombies’ (1953), ‘Voodoo Island’ (1957), ‘Zombies of Mora Tau’ (1957), ‘The Dead Live’ (1961), ‘Voodoo Swamp’ (1961), ‘The Plague of the Zombies’ (1966), ‘Dawn of the Dead’ (1978), ‘Zombie Flesh Eaters’ (1979), and more. Oh, and the personal favourite of the fraternity brothers, ‘Cockneys versus Zombies’ (2002). No doubt there a PhD dissertation or two charing the mutation of the concept of the zombie and its influence on…..