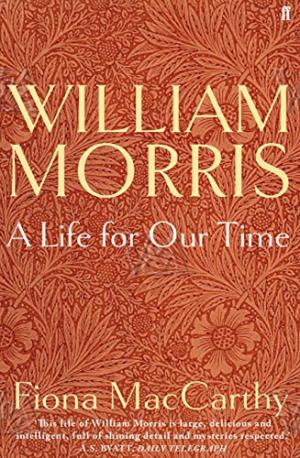

GoodReads meta-data is 780 pages, rated 4.17 by 115 litizens

Genre: Biography, Leadership

Verdict: a good book but so much detail that the man is obscured.

William Morris (1834-1896) was a poet, essayist, novelist, and more who was and is best known as a decorative artist. (He is not the William Morris [1877-1963] of the Morris automobile.)

Morris was born into comfortable circumstances in Essex. One of six children, his father was a broker who invested in mining (copper and coal). As a boy young Morris played at knights and lords, and that made the man. Most of us grow out of children fantasies, whereas Morris grew into them.

Medieval Europe was Eden before the fall of industrialism in his mind. He found the remnants of this past in cathedrals in England and France, and also in other ancient, rude buildings. That they were rough hewn showed they were made by human hands, and this he always preferred. He found continuity with this time of yore in the rough and barren landscape of Iceland, where every rock, tree, and crag has a name, and a role in an edda.

Two overarching themes dominated his creative life. One was to bring the past into the present, and the other was to bring nature into the home. The past and nature are unsullied and so they refresh the soul. To drink their elixirs we must drill back through industrialism, through the Enlightenment, and through the Renaissance to El Dorado.

At Oxford he came into the company of friends who stayed with them for the rest of his life, like the English poet with an Italian name Dante Rossetti, painter Edward Burne-Jones, and architect Philip Webb. This the germ of the so-called Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, reaching back past Raphael to an earlier tradition, and it was a brotherhood. Male companions were an essential in his life though there is not hint of an erotic element.

Influenced by John Ruskin, as later was the singular Marcel Proust, Morris began to look closely at buildings. Thereafter he treated them as repositories of human creativity, imagination, ingenuity, and history. Well, some of them. Those made by hand with tools made by hand, and so on. He founded a society with some of his inherited wealth to preserve historic buildings, which was one of the precursors of the National Trust.

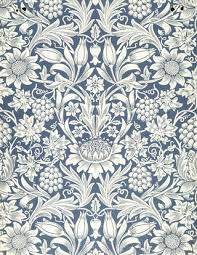

Morris began as painter of murals, and gouache works, migrating into interior design. Today to refer to Morris evokes a response about wallpaper with flowers and vines. Leaving aside many details, Morris was a cantankerous genius who made decoration into a fine art.

He threw himself into one thing after another, and mastered each from the ground up. To make wallpaper, first Morris made the paper. To make the paper he first made the presses and vats to make the paper. Only then did he devise the means to transfer his designs to the paper.

A Morris wallpaper.

A Morris wallpaper.

Tapestry is the same story. First he made the loom, then he made the tapestry. Later in life when he took up bookbinding. He once again made his own ink, paper, and presses so that the results looked medieval, free from the corrupting influences of modernity.

He was sure that the product that results from such wholistic labour was more authentic and superior, i.e., closer to nature and to the past, but he could never articulate that. Indeed, one theme in the book is that Morris, despite the endless flow of words from him in essays, novels, poems running to twenty-four hefty volumes in the University library, was unable to communicate. He could talk, he could write, but he seldom got across his essential meanings. The weight of his verbiage drowned himself out. This was especially true in his private life.

He married Jane Burden. She was not his social equal in Victorian England, and to prepare her for marriage they had a year-long betrothal during which she was tutored to upper middle class ways. They had two children, girls. The tittle-tattle about Jane is endless, and MacCarthy shifts it all judiciously. What is obvious is that when Morris proposed, it was an offer too good (socially and financially) for her (and her parents) to refuse, so she took it. Rossetti circled her for years like a moth to a flame; MacCarthy concludes that is all it was. Later she did have a paramour, and Morris knew this in all but word. He hated it and accepted it.

Morris had a volcanic temper and he gave vent to it often. I first tried to read this biography years ago, after reading his ‘News from Nowhere’ (1890), about which more below. After a time, I quit because I found him an unpleasant companion, with his tirades, self-indulgent jags, and perpetual spoiled child approach to life. Having persevered this time I find that only in his sixties did he seem to grow up.

The author handles this well and leaves it to the reader to decide. I did. Many speculate that he suffered from this syndrome or that. As if giving the pattern of actions a name absolves him of responsibility. Hardly. That syndrome was Jerkism. Often encountered for which no treatment has ever been devised.

In the 1880s the priest found his vocation, and Morris became an evangelical vicar for socialism. What that word meant to him is elusive. Overtly it put him in the company of Frederich Engels, Edward Aveling (and his wife, Eleanor Marx), Henry Hyndman, and others. These early English socialists were so uncompromising that if five were in a room there were seven factions claiming the Truth. They were only united on two points. (1) The current order is corrupt and unjust. (2) It is so corrupt and unjust that it cannot be reformed but must be destroyed. Thus they shunned the Chartists, the Liberal reformers like John Stuart Mill, and later the Fabians and the early stirrings of the Labour Party with their sewer socialism that offered practical improvement to the lives of millions but did not promise a city on the hill.

Socialism meant everyone had sufficient wherewithal to live a dignified and meaningful life. That honest work was the highest value. These are the basics of Morris’s socialism. His commitment was, in any event, not intellectual but emotional and he went at it for ten years like a man possessed. He funded socialist publications. He traveled the length and breadth of Great Britain extolling it by preaching on street corners, and so on. He exhausted himself. He also outspent the firm, the running of which he left to others: alienated clients, exasperated his wife, mystified many longterm associates, and perplexed his employees.

The jockeying for position among the socialist factions came to a point where he was turfed from the socialist organisation he had founded and funded. The plotters assumed he would continue to fund it since the cause was righteous. Naiveté has many names. He did for a time just as he put up with Rossetti’s years of attendance on Jane, but even he had a stop button. Much of the Wikipedia entry charts the torturous evolutions and convolutions of these folks.

After a decade of public proselytizing Morris retired from the field and returned to his workshops. Age caught up with him quickly and by the later fifties he looked much older and frailer, partly the result of untreated diabetes, and the long term effect of gout. Daughter May became even more important in keeping a Morris involved in the business.

There is a matter not resolved in this copious volume. May did not inherit the business or any part of it, though she was instrumental in it. One wonders why. There was no estrangement, and she began compiling his collected works shortly after his death and edited twenty-four volumes.

He seldom practiced what he preached, it has to be said. The workmen he employed were paid just enough to attract and keep them. There was no profit sharing. They called him ‘Sir’ though he often worked side-by-side with him. Peter the Great did that, too, but his workmates often called him Pete. He made no effort to contribute to their social or home life, or to educate their children. Robert Owen, George Pullman, the Rowntrees, and many other entrepreneurs did those things, while engaging in the industrialism he detested, but Morris did not. When confronted by the gap between his words and deeds his response was that one man’s actions were insignificant in the bigger picture. Immediate, practical, incremental amelioration did not interest him. It would only prop up the dreaded system. Never mind that such palliatives might enrich and save lives in the here and now. Rapture not relief was his ambition.

It is well to remember that he is not the only man to have inherited wealth. Unlike so many others he did something constructive with it and in so doing he also led others to do constructive work, too. In 2004 we visited Cardiff Castle in Wales, a lavish home, one of eighteen owned by the the Bute family who furnished it. Eighteen. The family spent no more than a week there in a year. Such riches, and yet not a day’s work done by any member of the family. That might be the comparison to keep Morris in perspective.

The book abounds in details. Sometimes more than enough is piled on for this reader. It is subtle in its interpretations with insight and clarity. The prose is supple. The book is a better companion than the subject.

Fiona MacCarthy

Fiona MacCarthy

We saw a superb exhibit on the Arts and Crafts Movement in Barcelona in April 2018 and that inspired us to do a William Morris tour of Adelaide in August 2018. This book was my assigned reading for the Adelaide sojourn. By coincidence I also heard an ‘In Our Time’ program on Morris, which is recommended.

Post Script

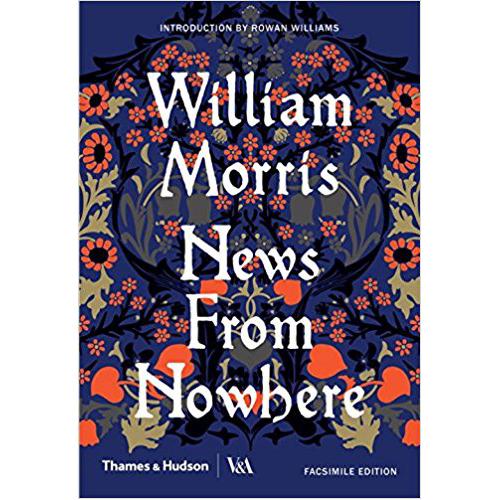

His ‘News from Nowhere’ (1890 has a place in the canon of utopia theory. He was moved to write it in refutation of Edward Bellamy’s ode to industrialism in ‘Looking Backward’ (1888). The two books have been since forever wed.

Bellamy celebrated the creative capacity of industrialism in the United States. Labor is organised like the armies of the Civil War and production was so great that there came abundance for all in return for a minimum service in the Industrial Army, which waged and won the war on want. Several innovations dot the story, like music piped into the home, like the credit card. It is a Rip van Wrinkle story in which a sleeper awakes to find this new order in full swing.

Bellamy’s book had an enormous impact, and it was this influence that drove Morris once again to his pen. His socialism was millennial. The old order had to be destroyed and only then could we find our way to the New Jerusalem. Gradual improvements were illusory sops, not change. Abundance would be destructive rather than liberating. Of course, only someone who already has all the creature comforts can dismiss them so easily.

Morris recoiled from this materialism finding it without soul. His rejoinder is another Sleeper Awakes tale. This sleeper awakens to a post-industrial world which has reverted to cottage arts and crafts, and everyone is happier for it, including the anti-vaxxers.

While Bellamy pictured the future as a continuous development with the present, Morris posited a rupture that overthrew the factory system and industrialism, and their attendant corruptions. Much of the book is devoted to the pleasures of arts and crafts, with nothing about tiresome necessities like clean water, sanitation, medical science, and communication.