GoodReads meta-data is 334 pages, rated 3.7 by 52 litizens

Homework for a proposed trip to Vienna next year.

This is part of series of concise histories.

This is part of series of concise histories.

History is just one thing after another, and in the case of Austria, the things occur here, there, and everywhere.

The book concludes with an outstanding summary of the paradoxes that comprise Austria today. In brief, the greatest Austrian is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart who was born and raised in Salzburg when it was not part of anything Austrian and he never thought of himself as Austrian. See David Weiss’s ‘The Assassination of Mozart’ (1971) for melodramatic account of just how un-Austrian Mozart was. I read this title long ago.

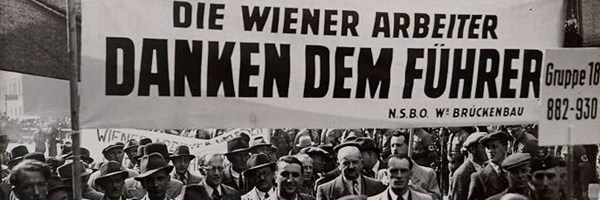

Austria came to exist as lines on a map at the end of World War I, then it disappeared in the Anschluss (which despite ‘The Sound of Music’ was much desired by most living within those lines), and then reappeared as another set of dotted lines in 1945.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire (AHE hereinafter) developed from the vestigial Holy Roman Empire and the Hapsburg dynasty. The latter at one time included Spain, the Netherlands, and much of central Europe in today’s Austria and Hungary and as far south as Bosnia. The Holy Roman Empire is even harder to pin down. Its emperor was selected by German princelings, though Prussia – the most significant German-speaking land – was not included. Got it so far?

The AHE was polyglot, multi-lingual, scattered, variegated, poly-national, and changeable.

Yet in its core it was German with a considerable and influential cosmopolitan Jewish population in Vienna. When it stumbled into the Great War, it was in fact trying to avoid war, but being inept, instead it precipitated it. Most of the dozen ethnic nationalities in the AHE wanted no part of Vienna’s war and withheld men, material, and food. By 1916 Germany had taken over the AHE in all but name, managing its finances, commanding its armies (in Italy, Romania, and Russia), running the trains, distributing food, and directing the home front. The war was a chemical bath that dissolved the AHE long before the Treaty of Versailles made it official.

The move for German-speaking Austrians to join Germany, even after the latter’s humiliating defeating of 1918, was so widespread and strong that the League of Nations forbade plebiscites on the question of Anschluss. Uniting Austria with Germany would have enlarged and strengthened Germany at a time when the League, i.e., is France, wanted to weaken it. Instead the League fostered the creation of something that have never before existed: Austria, a nation-state.

It consisted of a hinterland and Vienna, and the two had little in common. While Vienna had long depended on Hungarian grain, Czech manufactured goods, and Slovene timber, it had little truck with the new hinterlands attached to it. Some like Salzburg were altogether new additions.

The Depression hit Austria like a hurricane. As Hitler’s Germany rose from the ashes it was the light on the hill for Austrians, and now more than ever they wanted Anschluss, partly to escape the penury of the times, but also to reclaim its own Germanic essence, and to reject the cosmopolitanism of Red Vienna (where communists, socialists, social democrats, Jews, and liberals busily undermined each other).

When the producers of ‘The Sound of Music’ asked Austrian authorities for permission to stage a parade simulating the Nazi German entry into Austria, they were refused. Why? Because Austrians hate Naziism so much that even today the sight of such a parade would ignite a terrible reaction which the authorities might be unable to control. Oh, replied the producers, in that case they would use the ample newsreel footage of the rapturous welcome Austrian gave Nazis in 1938. Ah, replied the authorities, here is the permit for the staging.

It makes depressing reading to see how eagerly Austrians joined Naziism in all of its worst deeds. The enthusiastic enlistments in the SS. The ready subservience to the Gestapo. The quick denunciation of Jews. The vigorous competition to host and staff death camps.

Figure it out.

Figure it out.

Before 1938 there were more than 100,000 Jews in Vienna, perhaps 1000 survived by 1945.

Austria and Austrians were willing allies of Germany. Whereas Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and others were bullied and cowed into the Axis camp, Austria entered to the sound of music.

Yet in the 1943 Moscow statement, sometimes called the Treaty of Moscow, the Allies said Austria was the first victim of Naziism. Huh? That has never made sense to me, and even less so as I read the litany of its crimes with Naziism in these pages. But now I see the point.

It was one instance of a broader Allied strategy to prise Germany’s partners away for it by implying they would be treated differently. In this spirit when Italy changed government in 1943, it was readily accepted by the Western Allies. Likewise for years FDR kept lines open to Vichy France to dampen its enthusiasm for Naziism. Abraham Lincoln tried the some thing throughout the Civil War, trying to woo individual southern states, like North Carolina, away from the Confederacy with some success.

Stalin went along with this terminology for his own reasons, namely, if it didn’t suit him later, he would renounce it as fake news.

Abracadabra! In 1945 Austria left its Nazi past behind. It was occupied by the Allies until 1955 but the de-Nazification process there was perfunctory from the beginning. See ‘The Third Man’ (1949) by Graham Greene. In fact, it became a route for Naziis to get to the Adriatic and escape. Schools, hospitals, railways, manufacturers and others were ordered to destroy the records for the period 1938-1945. Others did so on their own initiative. The Brown Years were erased and blurred and a national amnesia settled over the new lines on the map.

During the post-war Occupation, the Marshall Plan poured money into the western part of Austria, while Russia stripped the Eastern part of everything from heavy machinery, to concrete blocks from buildings, to clothing, and dried food. The wire from concentration camps was taken down, baled, and transported to the Soviet Union where it was used in the Gulag. So effective was this scraping of the earth that by 1955 there was nothing left to take. Then the dotted lines became solid as a new Austria emerged from the cocoon of occupation.

But by 1955 a neutral Austria suited both the Western and Eastern blocs. There came the Austria we know today. For all of its superficial worldliness manifested in Vienna in particular, it is inward looking, reluctant to change, intolerant, industrious, frugal, and insecure, says the author.

I saw Kurt Waldheim speak in 1986 and he denounced foreigners, insofar as I understood the German. That was in Salzburg, a place that became Austrian by drawing lines on a map, whose major claim to fame is a festival which originated in the desire to reject modernity. The lederhosen of tourism in Austria was a way to cling to its (fictional) past and avoid modern life with trade unions, urban life, women’s liberation, unruly students, the interaction of nationalities (Jews), international influences, protestants, and so on.

When the Berlin Wall fell, Austria shrank from engagement with its historic affiliations in the East, and only diplomatic pressure – greased by German marks – and deft handling by some Austrian leaders overcame that reluctance to admit reality. Yes, Austria had taken in 150,000 fleeing the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, but only on the understanding that they would move on further west. Ditto another 100,000 after the Prague Spring in 1968. These were experiences few Austrians wanted to repeated in the 1990s.

Steven Beller has many other titles.

Steven Beller has many other titles.

While in Salzburg I heard an Austrian politician talk about the Brown Years of Hitler. One thing he said made perfect sense. We were disunited among ourselves, that is, even that minority who opposed Anschluss mostly argued against each other. After the war, the new Austrians of the new Austria closed ranks against all outsiders, and for these new people everyone else was an outsider, including even Austrian expatriates, Austrian Jews, and Austrians who were not German by language or Catholics by religion.

My next reading assignment is ‘Exact Thinking in Demented Times: The Vienna Circle and the Epic Quest for the Foundations of Science’ (2017) by Karl Sigmund.

When I went to Salzburg in 1986 I read Carl Schorske’s ‘Fin de Siecle Vienna’ (1980) and William Johnston, ‘The Austrian Mind: An Intellectual and Social History, 1848-1938’ (1972). I tried and failed to read Robert Musil’s ‘The Man without Qualities’ (1930). Not inclined to try again.

Skip to content