GoodReads meta-data is 296 pages rated 3.8 by 28 litizens

Genre: Biography with lots of natural science and some history.

Karl von Frisch (1886 – 1982) made a lifelong study of honey bees. He was cursed to live in interesting times and his story is as fascinating as the lives of the bees he observed until the week before his death. In 1973 he was awarded a Nobel Prize.

He was born to the comfortable circumstances into a Viennese family of learned and cultured cosmopolitans. He proved to be a naturalist even as a lad, collecting creatures, plants, objects galore, and he kept doing it thereafter. Some specialise in beetles or butterflies but not young Karl. Some grew out of this interest, not Karl.

He was a good student and went into medicine but the natural world called to him.

He answered the call first by studying fish in tanks to determine sensory perceptions. The experiments are ingenious, and that became a hallmark of his work. The experiments were also meticulous in execution. Another hallmark that continued. But the fishtanks were in the basement of laboratory and he found that boring, though he was never bored.

Then conversations with others led him to the perceptions of colour and scent in bees, and that led him to the waggle dance. The waggle dance? Yup. Why do honey bees engage in this dance. It had been observed since Aristotle without any interpretation. It takes time and energy and serves no apparent purpose. Yet it must.

This dance became an obsession to Frisch and from 1922 on he joined the dance. He trained bees and studied how they related to other bees. Trained bees? He would capture some scout bees, those that leave the hive first, and then put them in the presence of a shallow dish with sugar syrup. Yum, yum. This was all done in a meadow on a card-table. Many details and permutations follow, including draping dyed sheets over poles to make the bees easier to track.

In time he installed glass walls in hives to observe the inner workings of the hive.

He was an early adapter of movie films and began to record the experiments and observations which he used in teaching and at conferences. There emerged another hallmark of his work – the clear and simple expositions. He was glad to teach anyone and everyone about bees from school children to Nobel winning scientists. He attracted battalions of graduate students who carried the word of Karl far and wide.

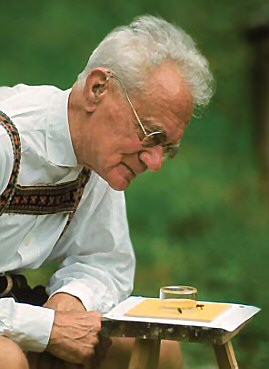

Karl von Frisch doing what he always did.

Karl von Frisch doing what he always did.

He needed them, because in 1940, much to his surprise the Naziis declared him Jewish. By then he was at Munich University where the Rockefeller Foundation had funded an institute for him. As a state employee he had to register with the regime and he did. In that time and place, nothing was ever done and in time the Registry Office found a marriage certificate of a Great Grand Mother that indicated that he had converted to Catholicism. That was enough. The inference was that she had been Jewish and converted. Nazi racism, perhaps it has to be said, was not about religious faith but race, and someone born Jewish never can stop being Jewish.

This discovery was a surprise to him and to his brothers. Frisch was classified Quarter Jew, and put on lists, forcibly retired from his university position, and denied the pension due to him. He was also suspect because to the Nazis the Rockefeller Foundation was a Jewish front. Hard to believe but there it is.

Many scientists came to support him, including a panoply of German Nobel scientists to no avail. An ideological hack replaced him.

Among his host of students many had gone into agriculture and apiary. Frisch’s supporters turned to these applied scientists to write letters and make representations about the practical and applied value of Frisch’s work to the agricultural authorities. They did and because agriculture was regarded as crucial to the Nazi war effort, these authorities advocated his case. The compromise was to make him emeritus and allow him after hours access to the laboratory facilities that Rockefeller money had built for him.

During the war he continued his research with bees. Munich was bombed flat. His home was destroyed and with it his personal library and all possessions. The Rockefeller laboratory was likewise flattened. He and wife moved to a meadow in the uplands of Austria and he continued studying bees.

When Nazi greed imported the Nosema virus by stealing tons of beehives from Russia and railroading them back to the Reich. Among the bees in those hives were carriers of this virus. In no time, millions of bees died. One of J. Robert Janes’s krimis concerns this plague, ‘Beekeeper’ (2001 ).

Bee research now became a priority. In that meadow he had a group of about twenty, students, assistants, and colleagues. Most of them had been in the war in one way or another. Most of the men were invalided out of the war, many with amputations. The women were often also carrying injuries from bombing. Yet there they were in the meadow with sheets, nets, saucers of sugar syrup, and the like.

As the war ground to an end, Patton’s army got to them before the Russians. After a day of watching tanks roll by, there cam a knock at the door. Gulp! At the door the American officer took off his hat and asked politely in German for Professor Frisch. He was on a list of German scientists to be located, identified, and recruited.

In time he became a good German, and rehabilitated and the Rockefeller Foundation once again supported him. The irony is that this good German was regarded as essential to the Nazi war effort and the Nazi regime funded his search during the war. He had only one interest and that was bees. He was not a German nationalist, or a Nazi. He lived for, in, and through science.

He found that bees communicated through the waggle dance, that they used polarised light in the sky as a reference point, and that they evolved. The scouts reported on the location and distance of food. There are videos on You Tube, including one by Frisch himself from 1926. The link is:

Tania Munz weighs and measures all of this with care, pulling no punches and glosses over nothing. It is an exemplary study of the man and his work.

Interspersed within Frisch’s story are vignettes about bees and other bee-obsessives that are delightful, and are integrated into the larger fabric. They add a dimension to the story.

The bees are almost always referred to as animals, not insects. Frisch is consistently called von Frisch though the Nazi regime stripped the von from names in the name of equality, breaking with the aristocratic past. Technically he lost his von.

In retrospect I cannot recall why he escaped Word War I. One of the limitations of the Kindle is flipping pages to find something like this.

I heard a reference to this book in ‘Exact Thinking in Demented Times’ (reviewed elsewhere on this blog) and found it intriguing.

Skip to content