GoodReads meta-data is 489 pages, rated 3.3 by 43 litizens

Genre: Non-Fiction

Verdict: Journalism.

N.B. I listened to it in an Audible reading. On that more later.

‘The Nobel Prize.’ Words that command respect far and wide. There are many prizes in many fields, then there is the Nobel Prize. Its origin and history is as interesting as its many recipients. More than 700 Nobel Prizes have been awarded since 1901.

Father Nobel was a Russian tinker, mechanic, and inventor who moved west, first to Finland, and then to Sweden. He took the name ‘Nobel’ in reference to the village in Russia from which he came. Father moved around a lot and experimented with explosives, which made him unpopular with many a landlord.

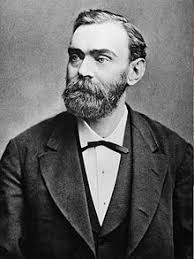

Alfred (1833 -1896) learned technical skills from his father, and he also learned the relevance of different jurisdictions for patents and copyrights. His two brothers went back to Russia and made enormous fortunes in oil. They were styled the Russian Rockefellers until the Reds came.

Alfred followed in his father’s footsteps literally and figuratively. He experimented with explosives and he traveled to and fro in Western Europe. He was polyglot from an early age, starting with Swedish and Russian, and later French and English.

His breakthrough was to control nitroglycerin which had been developed a generation before but had proven too volatile to be used. By trial and [kaboom] error he learned to soak it into a substance like sawdust and pack it into sticks. There followed the detonator.

He was careful to copyright and patent everything in every jurisdiction. He set up factories to produce his wares which far exceeded gunpowder in both explosive power and the capacity to be controlled in small doses. Typically he worked with local partners and was often content with the return from the intellectual property and a minority interest of 25-40%. He left management to these others.

Without TNT, let’s call it for short, the Suez Canal, the Brenner Pass, the Panama Canal, the great excavations for city subways might not have been possible. Nor would mining have unleashed copper, iron, and minerals as readily.

A given quantity of TNT had twenty times the explosive power of a like amount of gunpowder and it was also quickly converted into a weapon of war, and even in his lifetime Nobel was denounced as a merchant of death. That bothered and bedevilled him.

Nobel moved around, though he spent most of his time in France and seldom returned to Sweden after nine years of age. He never married and there is little hint of romance, sex, or marriage. He had a touch of the gloomy manner of a Swedish stereotype and became preoccupied with his will at a relatively young age.

In the last three drafts of his will he proposed prizes to recognize, honour, and reward those who had recently benefited idealistically humanity. Each of those adjectives became the subject of interpretation He added and subtracted prizes over the drafts.

The Peace Prize came late and is attributed to the influence of a woman friend. The terms ‘Peace’ came into being later. He referred to it as a prize to someone who done the most to avert and eliminate war.

The will named executors whom he had not consulted and who barely knew him. They were surprised and bewildered by the task. The will made no allowance for the expenses necessary to set up and establish the prizes funded by the interest from the bequest. Moreover, the will was disputed.

Distant relatives — cousins, nieces, nephews — all challenged the will. Nobel had written his will out in a letter without consulting a lawyer and so it was vague and devoid of legal formalities which encouraged challenges.

In addition, the sum of money was so great that the Academie Française argued that Nobel was French by residence and that the bequest should be established in France to be managed by …. [go on guess].

Only when the Swedish government intervened did the matter resolve itself, some five years after Nobel’s death. Even so there was little support for the wherewithal to create a permanent organisation and the Swedish government only slowly funded that. However, by insuring that the huge Nobel fortune was invested mainly in Sweden, stimulated the government to pay the upkeep for an office, heating for the rooms, postal charges, salaries for clerks and hotel bills for experts to make selections.

Nobel had also left instructions, albeit vague, about how the money was to be invested to produce an income for the prizes, and this, too, was challenged. The sum was so great that its investment in Sweden did much to boast Sweden into industrial competition with Germany, England, and France, despite being so much smaller. Those famous Swedish industrial names were in some part seeded by Nobel funds, i.e., Asko, Bophors, Electrolux, Ericsson, Kockums, Saab, Skanska, Volvo, and others.

Managing such a fund also gave the Bank of Sweden an international profile and experience that contributed later to its role in administering the Marshall Plan, which in turn gave Sweden a disproportionate role in post World War II diplomacy; an example is Dag Hammarskjold, a one time employee of that bank and administrator in the Marshall Plan. A biography of Hammarskjold is discussed elsewhere on this blog.

The impact of the Nobel Prize on Sweden was manifold. varied, and enduring. It also put Swedish scientists in the main stream of current research, and served as an entree into world scientific establishments. While scientists in comparable countries like Norway, Spain, or Italy were ignored, the Swedes were feted, and still are.

However the author is more interested in muckraking over the choice of recipients than in these long term financial, economic, social, and political dimensions.

The first substantial chapter concerns the literature prize. This was close to Nobel’s heart for he wrote plays and poetry in English and was an avaricious reader in several languages. The author points out some of the second-rate recipients of the Nobel Prize for Literature, especially in the early years when the process was inchoate, and that giants overlooked.

But the author makes no argument that these greats could have been selected. ‘Should have,’ yes. But ‘could have?’ There is only one prize a year, and even eliminating the second-raters, there would not be enough prizes for all the those omissions recited by the author. Indeed much of the book is lists of names that seems like a telephone book when listening.

While once I made it a point to read something by Nobelist in literature, no more. To this casual observer of late the Nobel Prize in Literature invariably goes to writers I have never heard of and do not want to do so. No doubt that attitude condemns me in the eyes of some. But criteria that are implicit in some the author’s fulminating are extent and durability. And I suspect many of the recipients in the last generation will not pass either test despite the lustre of the Nobel Prize.

The author also criticises the Nobel for not comprehensively covering all the literatures in all the languages in the world. This tirade is carried on and on. This auditor began to think even unpublished works would have to be canvassed to satisfy the divine criterion the author applied.

Perhaps the world’s greatest poet, composed poems on pages, which were then kept under a rock and never read by another, let alone published. The author seems to think that omitting such works undermines the prestige of the Nobel.

I blandly used the term ‘second-raters’ above to move the discussion along but reading the comments on novels on Good Reads leads me to conclude that any ostensible second-rater would have many ardent defenders. On Good Reads I have seen some of the most inane and pathetic novels stoutly defended by self-appointed champions, some of whom can spell.

Nobel specified that the Peace Prize be given by the Norwegian parliament in the recently independent Norway. This, too, was contested. Swedes had (still have but are less vocal about it) a low opinion of those truculent Norwegians, and regarded Oslo as the Nordic equivalent of a banana republic. Efforts were made to rescind that provision but international pressure and the distractions of the rest of the bequest preoccupied the Swedes and they let the Norwegians off the hook.

The author blandly assumes that identifying great works in the sciences is easier than in literature. He repeats that comment at the end of the book but when reviewing the science prizes he notes the faked results, cronyism, blinding ambition, citation clubs, organised national efforts to corral a prize. He notes the unintended consequences of science Nobel awards in distorting research agendas, either to get a Nobel or to follow in the wake of one. On this point I wished for more.

The author certainly makes clear that Nobel Prizes have became a major industry in Stockholm. It involves many committees, institutions, institutes, translators, evaluators, nominators, assessors, advisors, diplomats, clerks, managers, administrators, tech heads, and more. The activity is continuous and involves, offices, telephones, email, computer systems, a massive archive to be made digital, postage, travel, hotels, and more. All of this is done in absolute secrecy and so there is no way to estimate the cost in a year.

Secrecy is the order of the day for Nobels and it has been kept surprisingly well. I say surprisingly because leaks are the order of most days anywhere else. I would have liked some consideration given to why the rule of secrecy has been so successful there, when it is so seldom successful say for cabinet meetings, corporate boards, and examiner’s committees. For these latter meetings the secret results are usually broadcast before the written record is completed. Casual visitors to most Western European capital cities will be told state secrets within hours. The business pages spill the beans on secret corporate board meetings every Friday it seems.

I heard nothing about the origin of the Economics prize though the author spends some time in disparaging its recipients. As a layman, it seems he knows the worth of the work involved. He would not have ventured such remarks about physiology, I suspect. By the way, when I was Associate Dean in the Faculty of Economics I received a nominating form each year. I did not do so. But that fact indicates the massive mailing done.

Likewise I missed the chapter on the Peace Prize. Ergo I can give free rein to my spleen that Al Gore got one for being an insider and Barack Obama who got one for not being George Bush. Maybe he should not get another for not being President Tiny.

After years of Nobel Watching (think Kremlin Watching) the Nobel Foundation released the archives for the first fifty years. The author has great fun trolling through those for example of idiocy which can be found. While he acknowledges the daring on the part of the Nobel officials, say in making an award to William Faulkner in 1949 when his books were out of print and he was dismissed by such arbiters of opinion as the ‘New York Times’ as a village idiot. He does not go into the details of such selections but concentrates on omissions, like that of Joseph Conrad. Yes, Conrad was a great writer equal to any Nobel Prize winner, I agree.

However to get back to the view from my high horse, I also find that the author makes few, very few references to the acceptance speeches. Yet some of these in literature are even more remarkable than the works that secured the Prize. Faulkner’s ‘De Profundis’ is diamond bright.

Many questioned John Steinbeck’s stature, yet his acceptance speech burns with celestial fire. That the citation written by the Committee that selected him includes some inanities hardly diminishes Steinbeck’s work, though the author makes a meal of them. My point is not that an acceptance speech justifies post hoc an award, but rather than the acceptance speeches are part of the whole process of the Nobel and have a place in its history.

Many questions remain. How many people does the Nobel Foundation employ, full or part time? What role does the Swedish diplomatic corps play in facilitating the process? These remain known unknowns. How has the process changed with chaining technology? What kind of lobbying for prizes goes on? No single work could comprehend the whole, and perhaps there are others that have considered these questions waiting for me.

Above I noted that I had not heard this or that. Listening to it while walking or at the gym means some things get by me, and perhaps that in handling the device there are skips. This is hard to check without a table to contents with chapter titles.

The reading was staccato and grew ever more irritating. The prose was continuous but the reader imposed a staccato rhythm to it that made it sound like a breathless reporter from the rooftop. That made me reluctant at times to continue. No doubt on the Audible web site, there will be fans who loved that Hemingway drill delivery. Not me.

Skip to content