The Mummy’s Curse (1944)

IMDb meta-data is 1 hour of runtime, rated 5.6 by 2299 cinematizens.

Genre: Horror(ible).

Verdict: Ditto.

A pipeline project in the backwaters of Louisiana digs up Kharis (again) and off he goes; his lust undiminished by several millennia, dismemberment, and internments. This is one hard Mummy.

An archaeologist arrives at the construction site accompanied by a tarboosh-wearing assistant to confirm the investors’ worst fear. This movie is a turkey.

It is noteworthy for a film from this time that it is set in Louisiana. Most Hollywood films were located either in a big city like New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, or generic middle America. Even more unusual for the time, it features a variety of extras who are black, Asian, and Cajun. The human variety was seldom seen in Hollywood films of the day, except as comic relief. Here they are stereotypes to be sure but basically working men on the job.

There is also one very striking scene when the long dead Ananka rises steadily from the mud of the swamp. It is slow and nicely done. Regrettably, the unnerving effect of that scene is almost immediately spoiled when she appears thirty seconds later with a perfect coiffure, penciled eyebrows, false eye lashes, and lipstick (cosmetics which no dead Egyptienne would be seen without).

All this is supposed to occur twenty-five years after the Mummy’s Ghost (1944) but everything is the same; nothing has changed. Well, maybe that is true in Louisiana.

It just so happens that in the trackless swamp which a manager at head office thought would be a good place to lay a pipeline there is an abandoned monastery on a hill to provide a setting for Egyptian rites in the bayou: yes, a hill in a swamp. With it so far? Good. Hang on, there’s more.

When one character escapes no one knows where, but later another casually says he went to the monastery. Sure. There are several such continuity gaffs.

Then there is the incredibly clumsy staging as when the lurching Kharis stands two feet away from a character reaching out his hand, but no one notices, having checked their peripheral vision at the door. This happens a couple of times.

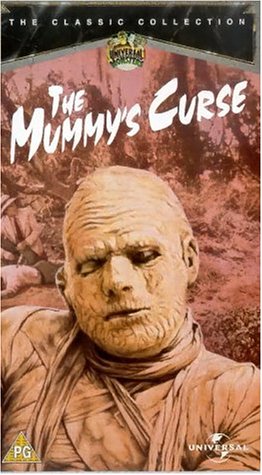

While Chaney-Kharis has his bad arm taped to his chest, but when he scoops up the maiden it is suddenly free, only later to be seen strapped up again. (Sssh. Be quick. Hope no one notices. [Psst, every noticed.])

The male lead is so far down the list I have forgotten his name as he delivered his lines in a monotone. But even worse was the evil Gypo priest under the tarboosh who was his assistant, sure, whose eyes flicked to the cue card to get his lines. But why bother. This evil priest was a Boy Scout. Where is real villainy when it was needed? Where was George Zucco? Or John Carradine? These guys could do menace. And they could remember their lines! Whereas this priest looks like he is dressing up to earn Eagle Scout points.

Martin Kosleck as the evil priest’s apprentice is far superior and should have had the major role. At least Virginia Christine can bug her eyes on demand. Addison Richards, Holmes Herbert, and William Farnum are reliable character actors in support and far more engaging, entertaining, and credible than the cardboard leads.

The shambling advertisement for gauze, Lon Chaney, Jr. returned in this vapid tale for the third and last time. As always he is completely concealed in the wrap and for all viewers know someone (or, even, something else) else might have been in there. Indeed, that raises the question of why such a name actor was cast and agreed to a part in which he never appears. He may have had little choice with his studio contract, but even so why use his talents in this way. Just to get his name in the advertising is the mundane but likely correct answer. And speaking of his name, on the opening credits he is ‘Lon Chaney’ and not ‘Lon Chaney, Jr.’ Huh? He was definitely a junior to his famous father.

This Chaney was born while his theatrical parents were on tour and made his first stage appearance when six months old and never left it thereafter. But he grew up in the shadow of the ‘Man with a Thousand Faces’ who had sired him. Chaney tried for years to create his own identity by using aliases, but he could never escape paternal legacy and gave up trying. In Wolf Man (1941) Chaney was gripping as the anguished and confused protagonist who could not believe but could not deny what was happening to him. It must be something like that when a mortal becomes a dean. But his greatest performance was the simpleton Lennie in the John Steinbeck tragedy Of Mice and Men (1939). See it.

This foul turkey was released on 22 December 1944 when the Nazi attack at the Battle of Bulge sent the Allied Armies reeling. More than 9000 GIs had been captured in short order and some of these POWs were then murdered at Malmedy. On this very day the soft-spoken, short-statured, and mild-mannered General Anthony McAuliffe entered history with one word reply to a Nazi demand that he surrender the beleaguered 101st Airborne at Bastogne: ’N U T S.’ This is the same unit — the Bastards of Bastogne — that later President Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican, sent to Little Rock to enforce compliance with a Republican-dominated Supreme Court ruling to integrate schools.