GoodReads meta-data is 110 pages, rated 3.96 by 324 litizens.

Genre: Biography (sort of).

Verdict: Wash your hands and fasten your seatbelts.

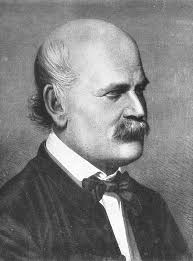

Hands up if you know Semmelweis (1818–1865)! He is the man who explained why we should wash our hands. His assiduous research into morbidly rates in maternity hospitals in Vienna led him to the conclusion that infections were transmitted by the hands of the doctors from one patient to another. From that finding he advocated hand washing and more hand washing. On that subject more in a minute, but first a few words about the book.

The Life and Works of Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis was an eighty-page thesis submitted to meet the requirements of the medical degree Céline earned. But there is nothing thesis-like about it. An indication of its tone and style hits the reader in the first lines: ‘Mirabeau howled so loudly that Versailles was frightened. Not since the Fall of the Roman Empire had such a tempest come crashing down upon men…. ‘ This opening passage goes on the characterise the French Revolution as a carnival of blood. Only three chapters later does Semmelweis appear, well, first his mother appears.

To return to the story, for that hand-washing advocacy Semmelweis was shunned, ridiculed, demoted, demonised, exiled, and finally driven mad; in the latter state he took his own life by the very infection he had identified.

Members of the obstetrics profession had long been resigned to high mortality in pregnant women, and accepted it. According to this upstart Semmelweis, doctors themselves caused these deaths! Ridiculous! Moreover, hand washing was undignified! Hmmph!

The fact that women who gave birth at home, or even on the street, had lower death rates than those who gave birth in all modern-conveniences maternity hospitals was written off as false news.

John Stuart Mill once opined that if the laws of geometry annoyed Republicans they would immediately declare them false. (He may not have mentioned Republicans but I got the hint.) Semmelweis’s intrusion upset a very elaborate and complacent medical establishment and the reaction was to shoot, stab, garrotte, strangle, quarter, and bludgeon the messenger.

In Paris, Prague, Berlin, and London as well as Vienna the medical profession united against this tiresome interloper and his pages and pages of data. In truth he was an easy man to reject, being rude and crude; he was quite unwilling to proceed by half-measures. It was all or nothing for him with the result that it was nothing. On more that one occasion he barged in the office of a hospital director and berated him about hand washing. Likewise he burst into wards when doctors were doing the rounds and berated them in front of patients and students. The Austrian emperor at one point exiled him because of these disruptive antics.

N.B. Semmelweis worked from aggregate data and there is nary a mention of a microscope observing little critters. That came later. What he had was a mass of data that showed a correlation between no hand washing and death. Reason and evidence are feeble assailants of the fortress of conventional wisdom and it took forty years for Semmelweis to be vindicated, and countless thousands of maternal deaths that soap and water would have prevented.

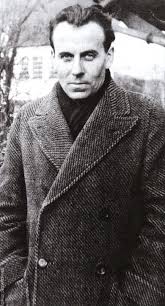

All of the above can be gleaned from the Wikipedia entry. And it bears little resemblance to the book at hand by one of the most remarkable figures in French literature: Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches (1894-1961) who used the nom de plume Céline. He was invalided out of the Army in 1915 with a wound at Ypres. Later he took a job with the League of Nations in Francophone Africa where he travelled extensively. Upon returning to France he trained as medical doctor and laboured in the working class districts of Paris where he was seldom paid. At the time he was a rabid communist only later to because an equally rabid fascist (and energetic anti-Semite) during the war years. He could be as rude and crude as Semmelweis.

His most famous novel was Journey to the End of Night (1932) about his observations in Africa, followed by Death on Credit (1936) about working class life and death in the slums of Paris. He wrote in the argot of the people he chronicled and not the stylised prose of the Academy and was thus reviled by the literary establishment for generations. These establishment gatekeepers are now gone and forgotten, while Céline is still in print.

Declaration of interest: One of the first reading assignments I had in graduate school concerned Semmelweis and his empirical data. That is all I can remember but the name stuck because of the association with hand washing.