GoodReads meta-data is 716 pages, rated 3.99 by 1152 litizens.

Genre: Fact and fiction.

Verdict: First in best dressed.

Herodotus (484–425 BC) wrote a history of the wars between the Persians and Greeks, with many, many digressions. Many. The book was a best seller in its time and because it was widely distributed it has come down to us nearly complete. Cicero called him the Father of History because Herodotus systematically pursued his research. True, he was a persistent compiler, but Thucydides hard earlier noted, as have subsequent readers over two and half millennia, that Herodotus made up some things and was credulous about others. Plutarch termed him the Father of Lies. What both Cicero and Plutarch agree on is that Herodotus was a superb story teller.

It starts with this statement: ‘Here are presented the results of the enquiry carried out by Herodotus of Halicarnassus. The purpose is to prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time, and to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by both Greeks and Persians; among the matters covered is, in particular, the cause of the hostilities between Greeks and Persians.’

While the Persian wars are the declared subject about two-thirds of the book is labyrinthine wanderings through Persia, Medea, Thrace, Egypt, Syria, Phoenicia, Scythia, and more. For those who open the book to read of these wars, there are 450 pages of digressions, tangents, sidetracks, and more. We might add to his sobriquets ‘Father of Digressions.’ Some of them are rattling good stories in themselves, but they add nothing to the description of the war when it finally comes.

As a determined swat in college, I first read an abridgement but gave up somewhere in the maze of digressions that remained in even that truncated edition. Since then I have dipped into it now and again for a specific point, usually following a footnote in something else I had read. A few years ago I also tried listening to an Audible edition, but lost interest as it sounded like the Old Testament: begetting, slaying, strangling, sacrificing, attacking, raping, the son of the son of, siring, murdering, banqueting, crucifying, dismembering, and cruelty in a variety of places I find on no map. He spends pages and pages on some minor kinglet just as he does on the River Nile’s ebbs, flows, and floods. The latter is much more important than an ephemeral king in some corner of the map, but not to Herodotus. And anyway, what does the Nile’s perturbations have to do the Persian invasion of Greece? Good question, Mortimer.

When Herodotus is not reporting on the gods but on facts, a lot of what he wrote is pretty solid, if not relevant to his declared purpose. In this he is like some thesis writers who crowd in everything they know. The surplus information conceals rather than reveals the point. This profusion of irrelevant details has led contemporary editors to abridge the book into a focus on the wars, and it is sometimes published as The History of Persian Wars, or Greek-Persian Wars, cutting hundreds of pages of stories, legends, myths, and so on. That’s the version I had in college but even so it was maze. This war only figures in the last three chapters (out of nine) of the complete work.

Among the good stories are the efforts by one people to ascertain which race of men was first by isolating from speech two children, carefully reared and nurtured by mutes so that the children never hear speech. When the children finally speak, this will be mankind’s fundamental language. The children do speak and none of those who hear them know what the language is, but decide – what a surprise – that it is an infantile form of the own language. Remember John Hersey’s novel The Child Buyer (1960)? Tsk, tsk.

Then there were the Persian notables who decided the best way to choose one from among themselves to be the new king was by whose horse first neighed at the next day’s dawn. Crazy, of course, but then look what elections produce in the way of leaders.

Then there is a wild ride on a porpoise, a tuna fish that returns a discarded ring, the gold digging ants of India, the winged snakes of far Araby, and more.

Oracles, there were a few. O’Henry may written some of them. An emperor asks if he should attack a rival empire, and is told that if he does, a great empire will fall. Aha! That means he will win! Off he goes to war. He loses. A great empire – his own – falls.

It is often downbeat as when after a long conversation near the beginning of the tome the wise Solon concludes that the only happy man is one who is dead. ‘Lighten up, Solly,’ cried the fraternity brothers! ‘Do we have to read all 700 pages of this by Beer Time?’ They had stumbled into the library by mistake and quickly scooted to the beer refrigerator.

There is no doubt from the text and other sources that Herodotus travelled far and wide in the Mediterranean world on his research grant, interviewing anyone and everyone he could, and scrupulously noting down what was said. Mostly he reports these interviews, even where they are inconsistent or contradicted by other interviews, but sometimes he does rule against something as absurd. At other times, when, say, writing about cloven-footed men he passes it on without comment. He also spends a lot of time measuring distances, buildings, roads, coast lines, and just about everything. Hmm, these exercises are made all the more confusing because of the variety of units of measure used. It is tedious to read and has no bearing on any theme but it does demonstrate his commitment to facts.

As to facts, when he does finally get to the Persian invasion there are many catalogues of allies, weapons, ships, crews, horses, wagons, hot dinners, spears, bunions, slings, woes, clothing, and so on and on and on. The result is that he enumerated the Persian army to be 1,700,000. With at least that many others following it as porters, teamsters, sutlers, prostitutes, astrologers (and other consultants), priests, and families. Quite impossible but that is what he has. Makes one think about hot meals, hygiene, and sanitation.

The Persian army was counted in this way. The first 10,000 men with their gear were herded together and as they squeezed in a rope fence was drawn around them. By the way, ‘myriad’ meant 10,000. So that was myriad one. Thereafter the rest of the army was put through this pen, and it had to be done 170 times to get them all. Then there was the navy, and allies who joined the throng later.

Two things emerge for this reader. A myriad is 10,000. And that is equivalent to a division in a contemporary army.

The other is this: One of the most trusted allies was ruled by Artemisia, a woman, who is styled a king in the pages. She went on the campaign with her troops, and attended the meetings, and in at least one she contradicted Xerxes. He heard her out and then politely demurred. She also led her ships into battle at Salamis with some tactical success, thus ensuring her esteem in Xerxes’s eyes. Herodotus is from the same town and might have had firsthand knowledge of this woman.

The historical Xerxes in these pages bears no resemblance to the infantile cartoon character in the egregious film 300 (2006). (Not to be confused with the superior The 300 [1962], but that is not saying much.) Although Xerxes was often cruel, pitiless, and vindictive enough to be a manager, but not always, and usually only when provoked.

Though the telling seems prolix (because it is) the major themes are power, greed, and stupidity. Eternal and contemporary these are; just watch the news.

Many speeches are presented word-for-word. Many. How Herodotus came to learn of them and the credibility he attached to them is unclear. Sometimes he presented two contradictory accounts, leaving the reader to judge. At other times he indicates which he finds the more credible. But how in the world did his sources hear, retrain, remember, retrieve, and recite so many long speeches. We’ll never know.

Despite the wealth of details two things are absent. One is the seasons and the constraints of the weather. Storms at sea are mentioned regarding the navies but little or nothing about the effects of seasons, climate, and weather on the armies. Second and likely more important are the language barriers. While Herodotus catalogues the array of peoples and nations among the Persian host and often recounts discussions between Greeks and Persians, and the speeches as above, he says nary a word about the languages used and how all these people understood each other. That is a puzzler.

Above I have emphasised the speeches because Thucydides often takes a beating for the thirty of so speeches he has in his narrative of the Peloponnesian War, though we know he heard some of them himself. The critics are sure he fabricated some of them. Yet we know that Thucydides also travelled far and wide researching his book.

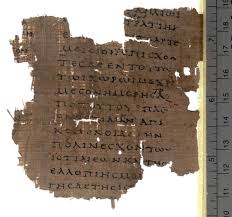

The edition of Herodotus I read on Kindle numbers the paragraphs in the customary way and divides the paragraphs into nine books titled with the names of nine muses although Herodotus specifically said he was not inspired by a muse but by the desire to record facts for posterity. See above. Lacking any first hand philological knowledge I do not know if the Greek text was set-out like that or whether this method of presenting the text came later like Stephanus numbers on Platonic and Aristotelian texts. Some paragraphs begin with a word in lower case or a comma and that indicates some missing text (I think). I would have preferred that to have indicated in the usual way. e.g., ’59 …. and then so on.’

We know nothing about Herodotus’s life save for his own few references. Only in the 11th Century AD did a Byzantine writer produce a biography (perhaps based on sources now lost) more than 1500 years after his death: A rather late obituary.

Gary Corby’s diverting krimi The Singer from Memphis (2016) features an amusing if obsessive Herodotus in the background. Extraordinary Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński’s reportageTravels with Herodotus (2007) is a handsome tribute to the inspiration of Herodotus. Is reportage really a word? The spell checker accepted it, but that is not a final ruling.