The Last Empress: Madame Chiang and the Birth of Modern China (2009) by

Hannah Pakula.

Good Reads meta-data is 816 pages rated 3.75 by 424 litizens.

Genre: Biography.

Verdict: Excellent.

Much is explained about Soong Mei-ling (1897/8-2003). As a boy her father worked passage to the United States on a merchant ship and left it in Wilmington (North Carolina) where he found a philanthropic sponsor who paid for his education at Trinity College (before it became Duke University). Having left China at four years old, first for Bali with his father, and then on State-side, he returned to China when he was twenty, a convinced Christian, accustomed to Western food, inexperienced with chop sticks, and committed to American ways with only a boyish smattering of the Chinese language.

He married an equally unconventional Chinese woman who sang and painted, practices usually associated with prostitutes, and sired six surviving children, including Mei-ling, giving each a Christian name, too, hers being Olive. He became a successful entrepreneur and to show his wealth and western ways, educated his daughters as well as his sons. Thus Olive found her way to Wellesley College (I gave a talk there once, or was that Wesleyan?) in the Connecticut woods where she had novelty value and soon learned to use that to her advantage. She maintained a lifelong correspondence with one of her roommates which is much quoted in these pages.

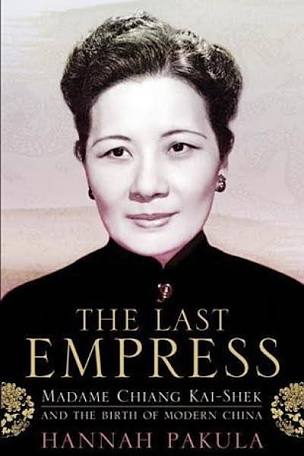

Already we see the woman in the girl. Her Chinese looks made her exotic to Americans, and her American ways made her exotic to Chinese, and she learned to use both perceptions to her advantage, and to switch back-and-forth from Chinese to American in a single conversation.

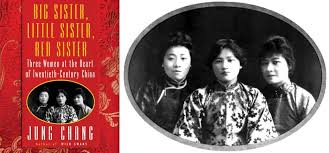

Like Charlie Soong, Sun Yat-Sen was well-travelled, imbued with America, a firm Christian, and an advocate of a new, reformed, modern China, and their paths crossed, whence they became friends and allies. Sun was the public face, while Soong became the bagman, securing funding through their trials and tribulations as the old regime tottered on its bound feet. The crucial times were just before the Great War in Europe, around 1910 -1912. Olive would have been about 14. When Sun married her older sister, they became family. She was a witness to the baptism of Twentieth-Century China.

There is much background about Chinese history which aids this reader in locating the characters in time and place, more history than one usually finds in a biography and that adds to its length. As a girl she was wilful, energetic, committed to a New China, took for granted the privilege of wealth, and resisted the pressures to get married young and be a good wife. There is a certain dilettantism to her New China commitment rather like Anglo champagne socialists. Never for a moment did she consider that a New China might have no place for her, that wealth might lose its privileges, that the coolies might want to govern.

The divide between North China (including Shanghai) and South China that had bedevilled the tottering empire remained and at times there were two would-be governments, one in Peking (the ancient capital of the empire) and the other in Canton or Nanking, vying for legitimacy, foreign recognition, loans, allies, and friends. Later the Japanese set up another in Manchukuo, while the Brits held on to Hong Kong.

The Chiang Kai-Shek who appears in these pages is an ambitious and unscrupulous man, but one so lacking imagination he can (possibly) be led. He wanted to marry Sun Yat-Sen’s widow (think Richard III), but she reviled him, and so he settled for her younger sister, Olive, who was more pliable at the time, to gain the social status and financial connections of the Soong family one way or another. Like Henri Quatre he converted to get them, from a nominal Buddhist to a nominal Methodist.

His only purpose was uniting China (under neo-emperor Chiang) by absorbing the fractious war lords who had emerged from the decay of the ancien régime, and this focus distracted him either from the Communist whom he underestimated and the Japanese whom he feared. For her part, Olive did occasionally try to improve the lot of ordinary people through charity and war work, but the scale of China was beyond ever her considerable energies and wits. Chiang could never quite subdue the warlords and the 1920s and 1930s was period of constant conflict somewhere in the celestial kingdom. While he negotiated with this warlord or that, the Japanese decided Manchuria had the resources and industries that Nippon needed to join the Great Powers, and so it annexed what had been the richest and most stable region of China while Chiang continued to play warlords. He accepted that as a fait accompli from his bastion in the South.

Stubborn to the core, Chiang never changed, and when war with Japan became inevitable he stuck to the belief that others (the European Great Powers, the USSR, and the USA) would have to defeat Japan, and meanwhile his purpose was to prepare for the eradication of the Communists to consolidate his rule of China. Olive was steadfast and exercised considerable influence over him as amanuensis, translator, negotiator, advisor, observer, charmer, champion, and loyal operative. She articulated and advocated a social program of sanitation, education, communication, and the like, much of which was embodied in the New Life campaign, but throughout Chiang’s regime the army absorbed at least 40 – 60% of the budget by all estimates. Since the wealthy middle and upper classes who supported Chiang paid no tax, and collecting customs from the International Zone of Shanghai and other Treaty Ports was impossible, the financial burden fell on peasants, who were taxed two or three times a year to amass the wherewithal for yet another campaign of final eradication against another warlord. Olive had a finely developed blind eye for much of this oppression.

Aside, she did not have a sustained and concrete project in the way that Eva Peron did for the shirtless ones. Olive’s good works seem more infrequent and dilettantish than Eva’s. Nor do they compare in scope or depth to Eleanor Roosevelt’s contributions to domestic politics.

Uniting China would garner international recognition for Chiang’s government, and that would allow him to raise funds for the army (oh, and for those social programs, if there was any left over, though it never was) from international banks. That was the logic of his focus. To unify the vast, disparate, and querulous regions of China, Chiang looked to the model of European fascism for order and discipline. Olive had the rhetoric of constitutional democracy from her American years, which he learned to tolerate, but never himself espoused, although as his translator Olive sometimes put such phrases in his mouth.

During Chiang’s long ascension he was at times courted by both Stalin and Hitler. Russia wanted a bulwark to hobble Japanese threats to its Far East (including the buffer state of Mongolia), and if the Communist and Nationalist cooperated, China might be strong enough to impede Japanese access to its natural resources. Hitler, on the other hand, simply wanted to bedevil French and British interests in Asia, and so on occasion invested a little time and money in wooing Chiang to undermine the Europeans. In fact, during the early stages of this second Sino-Japanese War in 1938 Chiang’s principle military advisor was a German general — Alexander von Falkenhausen — to whom he seldom listened, but who had trained and equipped several Chinese divisions, which proved to be the best in the Nationalist army. These troops were so good that Chiang tried to withdraw them from combat with the Japanese and reserve them for another eradication campaign with the Communist, a plan that came unstuck when these units became the core of American General Joseph Stilwell’s Chinese Expeditionary Force in Burma. CKS quid pro quo for these troops was a pipeline of Lend Lease material through Burma.

There is no doubt Madame Chiang was a force. At one point she was the official head of the Nationalist Air Force and instrumental in recruiting, retaining, and giving free reign to Claire Chennault to run it over the objections of many Chinese generals who wanted access to the prestige, money, and goods that went with it. She was the only one who could get Chiang to bend or even change his plans. With all others he was stubborn because he aspired to the infallibility of a son of heaven emperor.

(Chennault was an exceptional flyer, trainer, and organiser of pilots, until he developed a Napoleonic complex and tried to influence grand strategy. His strategies always made him the centre of attention and never worked and that was alway the fault of someone else.)

The oceanic corruption in the Nationalist regime was the price the Chiangs paid, on this telling, to retain allies and subordinates in the vast, fractious landscape of China. Trying to eliminate it would have toppled the regime, per this author. Best then to try to manage the corruption by participating in it! To illustrate the effect of this corruption. The American manufacturer of an airplane would sell it to a Chinese agent for $1,000 who paid for it with Chinese government money but the agent would then change the invoice to $4,000, pocketing the entire sum. Nor were all the $4,000 planes ever delivered despite the payments. Some were sold at the price two or three times. To fund these outlandish prices much of the money raised for Chinese War Relief (of Civilians) by Madame Chiang was siphoned off to these war materials. (There are occasional references to this Relief fund in the contemporary Charlie Chan films.) Without a doubt members of the Soong and Chiang families participated in this profiteering. Strange but this story reminds of a recent crime family’s occupation of the White House.

The disjunction between Olive’s rhetoric of the rule of law and democratic equality and the reality of her personal behaviour is brought home in numerous instances. She used people and once she got what she wanted from them, they disappeared from her consciousness. One day you were her dearest friend, and the next day she looked through you. Servants were treated like slaves, and there were many servants, and she treated many people as though they were servant-slaves, and so ingrained was this haughty manner that it was manifested even in her wartime visits to the United States and Canada when she was tying to win friends, so much so that the press got wind and word of it and her halo started to tarnish. Her speeches, by the way, on this trip are marvellous, though occasionally there are some obtuse passages that would make a Jürgen Habermas proud. Two things are clear: she wrote nearly all of her own speeches and she was good at it. Second, she relied on a dictionary with little sense of usage. She too long retains a sophomoric desire to impress auditors with long and unusual words culled from dictionaries.

While she was in the States raising money for Chinese war orphans, she booked a floor of the Waldorf Hotel for many thousands of dollars, and went on a mink coat shopping spree, purchasing ten, with all the associated accoutrements which added up to more thousands of dollars. This booty had to be flown into China over the Himalayas where every fourth plane crashed, often killing the American crew. This, too, the press sniffed. The author shows, piteously, that much the money raised for orphans went straight to the Soong family, including Olive. (It seemed to me to be a parallel with the argument Pericles made about the Delian League. Think about that!)

When Wendell Wilkie visited China in 1943 he was completely enamoured of Olive and she wrapped him around a little finger, assuming he would succeed FDR. Therein lies a juicy tale for readers of this book. Check it out for yourselves. He thereafter became the number one cheerleader for Kuomintang (KMT) China. No reality check dissuaded him. Much of Wilkie’s memoir One World (1945) is an ode to (Madame) China.

While it is not emphasised, in passing the author makes the observation several times that the the Chinese penchant for avoiding embarrassment and humiliation (face) meant that bad news was not reported. If an army division was destroyed, the report would be about the heroic salvage of spare tires or some such trivia. And Chiang made that cultural reluctance worse by frequently, sometimes literally, shooting the messenger.

An Australian journalist (William Donald; there is an informative entry about this accomplished individual in the Australian Dictionary of Biography) who was undoubtedly smitten with her became her full-time press agent. His coaching and advice did much to create the public image of Madame Chiang.

The book explains much of the post-War hysteria about ‘Who lost China,’ which radio pundits were still rehashing in the 1960s, e.g. Thomas Dodd, Paul Harvey, and Walter Judd, among others. General Joseph Stilwell and his ilk were renounced by the pygmies in D.C. after his 1946 death for his efforts to cooperate with Chou En-lai to fight the Japanese. He had one meeting with Chou who agreed to obey his orders, but Chiang refused to cooperate with Chou on any terms. In the other corner were are all those deluded missionaries who believed Chiang’s superficial commitment to Christianity and overlooked the palpable corruption, cruelty, and incompetence of his regime. Reminds me of the evangelicals and the other guy. No sin is too egregious as long as he holds up an unread Bible. It became obvious by 1943 that CKS had no legitimacy in the parts of China nominally under his control. He was but one war lord among many, with this difference: He had Olive to present him to the world. But no amount of American aid or intervention would have propped up the rotten KMT regime for long.

CKS and KMT were unable to change. All appointments and promotions in the government and the army were based on personal loyalty to CKS, and not competence, ability, motivation, skill, or anything else. The only criterion was loyalty to Chiang. The only thing that trumped loyalty was kinship. CKS appointed numerous, distant relatives to important jobs, though they were unable to perform the duties, having them in place blocked out others who might not be so dependent on and loyal to Chiang. While the nepotism crippled his regime, he never changed it. If anything the transfer to Taiwan exacerbated it.

The native Taiwanese population were not regarded as Chinese, and so by definition they were disloyal to the embodiment of China, namely, Chiang, and, moreover, they had to be displaced to make room for those loyalists who followed CKS to the island. Hence upon arrival his army purged the islanders from administration, education, business, army, and the like on the grounds that they were all communists, many of whom were murdered. Nor was any of this secret. US State Department officials witnessed, documented, and recorded it, but such facts bounced off the Christian China lobby in D.C. (Nothing ever changes with god-botherers.) The result was to shoot the messengers in the McCarthy hysteria.

Soong Mei-ling outlived Chiang, and just about every one else, spending her last thirty years in the States, dying in (1898-) 2003, an unreconstructed Cold Warrior. Olive was manipulative, sly, persistent, wily, played a long game, a user, a snob, a marvellous orator, a much stronger personality than CKS, a power seeker, tyrannical, oblivious to her own contradictions, imperious, a speaker of many hollow phrases, a patriot, without self-knowledge or doubts, and much else. All that said, and more, she was one of the half-dozen major players in World War II, and the only woman to have that role.

It occurred to me that Olive and CKS might have played good-cop, bad-cop in their dealings with the Yankees. He was intransigent and never gave inch so when she asked for the moon it seemed reasonable compared to him, often with the result being they got a lot of what they really wanted.

She had more direct influence over Chiang and his government than, say, Eleanor Roosevelt had with FDR administration or Eva with Juan Peron.

Oddity. Her older sister had married Sun Yat-sen early in the Twentieth Century, and as his widow she tried to adhere to his vision of China, often denouncing, sometimes publicly, the CKS regime. When the Communists took over the country, she chose to stay in China with the masses, and she was regarded as a living embodiment of the continuity of the new regime with Dr Sun, and sequestered in comfort. She likewise occasionally, and publicly rebuked this regime, too, especially during the Cultural Revolution. Her symbolic value was so great that these remarks were overlooked by Emperor Mao.

The book charts Olive’s growth and change from a cloistered college girl to the dragon lady whose death was not mourned by a good part of the population of Taiwan, despite the official gloss. Though she lived in the States for years she continued (to try) to influence Taiwan politics in favour of the old guard (and her family), and her extravagant living arrangements were funded by US Aid money meant for Taiwan. When her house was cleared post-mortem, one closet was found stacked with cardboard boxes of US dollars on top of piles of gold ingots. Rainy day savings.

The author has distance from the subject, and does not take anything at face-value. Yet the picture of Olive is understanding, if not sympathetic, and the digressions on context were informative to this reader (otherwise ignorant of Chinese history) though they added considerably to the length of the book. However the book lacks a last summing-up chapter which I missed. After all the details, a final chapter that weighs things up is valuable but rare in biographies. It seems biographers are exhausted at the end, and just want it to done. Editors are so jaded they have no interested in the needs of readers, and so this book ends without a reckoning apart for a few passages from obituaries.

The author seems to specialise in royal women with other biographies of Prussian Empress Frederick who mothered Kaiser Bill and Queen Marie of Roumania.

Kate had a distant brush with Madame Chiang in Rees family lore. Kate’s mother bred dogs, scores of them at time, and sold one to a local agent acting, she was told, for Olive sometime in the 1960s.

She gave one of her anti-communist speeches at Nebraska Wesleyan University in Lincoln on 30 September 1966. I expect I read about in the local newspaper at the time, but have no recollection. I was just starting my sophomore year of college a hundred miles away.