GoodReads metadata is 1120 pages, rated 4.11 by 81,479 litizens.

Genre: Biography.

Verdict: Chapeaux!

At thirty-three, single, and out of work, when the U.S. entered the Great War Harry S. Truman joined the Army. His life changed thereafter. He became the Decider-in-Chief.

The efforts outgoing Democratic President Truman made in 1952 to smooth the transition to the incoming Republican President Dwight Eisenhower make poignant reading after January 2021. Truman spared nothing to put Ike into the office within hours of the election result, being motivated both by the national interest that transcended and dwarfed his own feelings, and his abiding respect both for the electorate and the office as well as his personal admiration for Ike. Read on.

That ’S’ was put on his birth certificate because his parents could not decide which grandfather’s name to put there, both beginning with ’S.’ And they never got around to changing it. Thus neither felt slighted, I guess. Such indecision would not have suited Truman in his prime, when getting things done meant deciding right here, right now.

Born to modest circumstances, he started wearing glasses and being bullied for it at an early age. He took to music and his parents made sacrifices so that he could have piano lessons and later as a high school student he worked several part-time jobs to pay for his own lessons. He saw some great classical performers in Kansas City (which contrary to the belief of the other guy was and is in Missouri). While in France during World War I he discovered opera and spent his money on that. He was bullied for this girlish interest in music, too but it remained with him all of his days.

Somehow he always remained cheerful, energetic, and ready to work.

He had two months of intense combat during the Argonnne offensive, including direct fire. (The redlegs out there will know what that means and it is not good.) Truman had been over age and blind in one eye when he enlisted but lied about his age and memorised the eye chart. In this as in much else when he decided, he finished what he started.

As a farmer and a store clerk by experience he was well suited to the 1917 army. Farming meant he was accustomed to supervising the work of a dozen or more seasonal hired hands, using horses, digging trenches and dikes, keeping machinery and tools in good repair, and monitoring the weather. His clerking meant he could read the artillery tables, keep an inventory, and insist on order the routine. He commanded a battery of four guns with about 200 men, most of whom returned to Missouri and soon became his first constituents and lifelong supporters. Some were still marching with him in 1952.

In the army he became friendly with a scion of the Pendergast family and in time that mob recruited him to run for political office. It was a case of opposites attracting and while the relationship was not always smooth it amused the Pendergasts to have an honest man in their ranks. His organisation, attention to detail, energy, and determination made him a productive county and later state supervisor who got roads, hospitals, schools, and bridges built and repaired while saving money. He did much of this work on site meeting people, not ensconced in an office in KC and soon gained more responsibility.

Truman liked making things happen, liked being out and about meeting people who would use the bridges and schools, and soon aspired to ever higher offices at the State level or even Congress in distant Washington. He was an enthusiastic Franklin Roosevelt supporter as early as 1924 and voted him at the nominating convention in 1930 and never strayed from that path, though Senator Truman did vote against the Supreme Court packing, and opposed FDR’s third term, facts recorded in the White House.

Quite how Truman avoided the Pendergast enterprises of prostitution, boot legging, tax evasion, profiteering, influence peddling, illegal gambling, tax evasion, and more is not specified. The Pendergasts focus on Missouri meant it was easiest to send their tame honest man to the Senate where he would not interfere with their profits and so he went to Washington where he kept his mouth shut and his head down for a time. He sat near another notable Senator, Huey Long of Louisiana whom he detested.

His first term was unremarkable, but when re-election loomed the Pendergasts support shifted to another candidate (for the same reason, to get him out of Missouri), and in the ensuing three-way race the pundits of the St Louis and Kansas City Press placed Truman third.

This was an all of nothing race for him. He was fifty and broke. The farm had long since been sold by his sister. He campaigned in a car and criss-crossed the state. He was not a good platform speaker but he was sincere and he worked the crowds before and after the speeches until everyone went home. That is, he never quit. During the thousands of miles he racked up, he often slept in the car since he had no money for hotel rooms. He never gave up! He never surrendered! By Grabthar’s hammer he won! In a way that victory foreshadowed 1948, as the cognoscenti know.

He returned to the Senate in 1941 now clearly his own man, while in Missouri the Pendergast gang was being dismembered by Federal tax evasion prosecutions, which also dragged down both of his opponents in the Senate re-election campaign. In all these investigations which went on for years, no link was ever found that led to Truman though the investigators looked hard for it (after his above mentioned opposition to FDR’s third term).

He became chairman of a special Senate Select committee on war procurement and that made his name. He had seen waste and profiteering in war contracts in Missouri on a grand scale, and supposed it was a general malaise. When he proposed an inquiry there was much opposition in the name of the emergency, and FDR had no interest in riling contractors who would be major donors to future campaigns. One man stepped forward in support, and that is all it took. That was George Marshall. He volunteered to testify and appeared as the first witness. That set the tone for all that followed and began their lifelong bromance. Years later Marshall estimated that the Truman Committee, as it came to be called, cut costs by 25% and raised quality by a like amount in war industries. Its revelations were breathtaking in the audacity of the crimes revealed, far beyond anything Boss Pendergast would have dared. Reading the excepts from the testimony is, well, depressing. See Arthur Miller, All My Sons (1946) for another perspective on this sad chapter.

The Truman Committee made Harry a national figure. Hearings and investigation were held here, there, and everywhere, and Harry was ever-present. As chair he was unfailingly polite and considerate and seldom spoke in public sessions beyond the need to order the agenda. The Committee was bipartisan and it focused on facts. (Remember those?) Over the years it issued twenty-five reports and made four hundred recommendations. Each report was unanimous and so was each recommendation. That was the first and last time such a bipartisan ad hoc committee had such unanimity. Put that down to Truman’s endless smoothing of the members and his absolute insistence on facts, and nothing but in their private deliberations.

Then came the big ticket. FDR changed Vice-Presidents like his shirts. While incumbent Vice-President Henry Wallace wanted to hang on, in 1944 he was perceived to be past his use by date. The ultra-liberal Wallace, a civil rights advocate, and one who flirted with Communists was deemed a liability in both north and south this time. (In 1940 with his recent exemplary record as Secretary of Agriculture to compensate, he had been an asset in the South and West.) The obvious choice was Senator Jim Brynes who knew the presidency better than anyone bar FDR himself, but he was a southern Roman Catholic who was a racist. He would be a liability in the North and West and not an asset in the South because of the Catholicism. Many others were considered and still others put themselves forward. As was often the case, FDR was inscrutable.

Moreover, and this was news to me, nearly everyone in the inner circles (there were several inner circles) realised FDR might not live out the next term. In choosing this Vice-Presidential candidate they were nominating a president to be, or as one wag put it, in this convention two presidents would be nominated. There were even those who feared that FDR would die before the election and that would make Henry Wallace president, so palpable was the worry.

Truman got the nod for these reasons: No one was against him. He was acceptable to organised labour; he would not antagonise the black vote in the north nor alienate the white vote in the south; he had impeccable New Deal credentials; he was staunch on equality before the law; and though only four years junior to FDR he appeared youthful and energetic in comparison. That latter was an asset when he proved to be a vigorous and likeable campaigner, though he was never an accomplished speaker in a way that became an asset for it made him seem ordinary, ‘one of us,’ as many auditors told journalists. The 1944 Democratic ticket was also aided by the ineptitude of the Republican campaign of Thomas Dewey as below.

For his part Truman realised that in taking the nomination he was likely to become president. Indeed he was among the shortest serving Vice-Presidents, holding the office for eighty-two days.* Yet as the biographer shows he made no effort from the nomination in July 1944 to prepare himself for the higher office. Quite how he might have done that without seeming presumptuous is anyone’s guess.

Then came the message one day while he was presiding over the Senate. A handwritten note scrawled by FDR’s appointments secretary and delivered by a sweating messenger to him in the well of the Senate asked him to come to the White House right now! He ran most of the way as if he knew what the news was. The whirlwind followed.

After years of FDR’s prestidigitation, oracular vagaries, rhetorical heights, sly manipulations, sleights of the tongue, temporising, increasing lethargic mien, Harry S Truman was a cyclone in small and large ways. Where FDR with his ten-pounds of steel braces was ponderous, Harry was a jack rabbit and the Secret Service men soon discovered they could not keep up with him. Items that had languished on FDR’s cluttered desk for months or more because with his declining energy were briskly dispatched. The office staff accustomed to FDR’s deliberate pace were unprepared for this barrage of decisions.

The biggest ticket in all this is Special Project S-1. Truman knew nothing about the Bomb until the twelfth day of his presidency when the Secretary of War, the redouble Henry Stimson, asked for an interview and brought in a two-page summary, along with General Lester Grove to elaborate. So secret was the project that this two-page paper had been typed by Groves himself and it was not sent ahead in the usual way but carried by hand. There followed the most momentous event of Truman’s presidency. The hindsighters have made careers out of being holier than thou about this, but to read the process in context it all makes sense. There are many threads in this tapestry but one that new to me were the intercepted Tokyo cables to the Japanese ambassador in the then neutral Soviet Union in April 1945 declaiming there would be absolutely no surrender on any terms. At best the Soviet Union might broker a truce, nothing more. (For those dozing in history class, the US had cracked the Japanese naval and diplomatic codes in 1941, but not the army one.) Everyone in Washington, but few members of the Hindsight League, recalled the Japanese continued negotiations in December 1941 even as the attack fleet turned into the wind to launch the first wave of aircraft. (I also learned why fire bombing in massed raids occurred in Japan and not Germany and that, too, had a logic to it.)

To that date in April 1945 no unit of the Japanese army or navy had surrendered at any time. That left the million-man home army and its civilian auxiliaries (women trained to stab with cutlery and children to strap on explosives), another million soldiers in China, and a third million in South East Asia to subdue. Would each one of them fight to the death? That seemed a possibility. Pentagon planners estimated one million US casualties to overcome these forces, assuming that they fought as tenaciously as had those in Okinawa and Iwo Jima. Thirty divisions of the US Army in Europe were being re-fitted for the Pacific, and in the Pacific rear echelon troops like MPs (including my dad) were being trained in assault firing. Little was expected from the depleted Allies, Great Britain and the Soviet Union, beyond a symbolic participation.

One of Truman’s early acts was to appoint a new Secretary of State. Why had he bothered to take the time to this in the urgency of the circumstances? Because according to the Constitution of the time, the Secretary of State was now next in line for presidential succession and he wanted to ensure it was someone who could govern if fate took that turn. That is presence of mind.

There is a detailed discussion of the Potsdam Conference where the primary American objective was obtained, a Soviet commitment to enter the war against Japan no later than 15 August 1945. Everything else was at an impasse and there remained.

As soon as the war ended, domestic politics descended into chaos with labor strikes large and small, price manipulations by big business, corporate shenanigans on Wall Street, back-biting in Congress – in short, business as usual. Truman had hoped the unity of purpose during the war would continue in the face of the incipient Cold War. Not so, and he floundered for some time, but finally arrived at the conclusion that he had to act, and did, winning no friends but bringing some order to affairs. He was likewise distrustful of the Soviet apologists in his own ranks, like Henry Wallace but felt unable to act against them without creating more instability. The incompetence and corruption in the IRS shook his faith in government, but he bit that bullet, too.

But all of this was only just the beginning when came the Berlin Blockade, the Marshall Plan (which he got through a Republican Congress), the Greek Civil War (initiating the Truman Doctrine), Soviet delay in withdrawing from Iran, and one crisis after another end-on-end. As it was his strength so it was his weakness that he did not want to discuss problems but to resolve them and resolution was by a presidential decision, and damned the torpedoes, he made them. When he made mistakes, and he did, he just as quickly corrected them, but it was always full steam ahead for this land lubber.

Not all the crises were international. The House Un-American Activities Committee undermined by hyperbole, innuendo, and lies most government institutions. In this context Truman appointed David Lilienthal (of the Tennessee Valley Authority [TVA]) to head the newly created Atomic Energy Commission and that set off a long-running fire storm. The Army opposed civilian control of nuclear energy, and ergo any appointment. Senate Republicans saw in Lilienthal an easy target and went after him with little or no scruple. The fact that at the TVA he had done more concrete good for more people than all of the cannibals combined only proved to them that he was a pinko, if not worse. (On the TVA see ‘Wild River’ [1960] for enlightenment. Roger Ebert said it was Elia Kazan’s love letter to the New Deal.)

When Truman offered Lilienthal the job, Lilienthal had predicted a difficult confirmation, and Truman said he knew that and would see it through come what may, and he did.

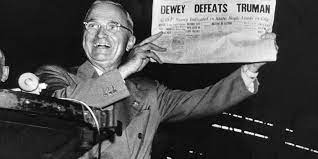

The 1948 campaign had many unusual and remarkable features. Too many to enumerate here, but election junkies will find it worth reading those chapters. I will limit the keyboard to two of them. The polling showed Truman behind 3 to 1. In 1946 the Republicans had already secured comfortable majorities in both houses of Congress. Yet Truman never doubted he could win and infused his entourage with energy, if not belief.

Truman’s masterstroke was this. The Republican nominating convention produced a platform for the election of proposed legislation, which was largely modelled on the current situation. Their claim was that they could do it better, not that it was much different from Truman who was an accidental president, a common man in over his head, and an incompetent (and by innuendo, corrupt).

Leaving aside that insulting rhetoric, Truman found little to dislike in the Republican platform, but he doubted that it represented the reality of a Republican administration. To test that proposition he did the following.

He called Congress back into special session during the campaign and dared the Republican majorities to pass the legislation proposed in the campaign platform into law: unemployment insurance, low cost housing, immigration extensions, farm price support, and so on, and on. If they pass it, I’ll sign he said. If that is what Republicans want, they can have it now.

Congress duly assembled in the sauna that Washington is (at a time when air conditioning was scarce) and…. Well, all that platform was publicity and did not represent the intent of the GOP, and instead of passing bills, they spent the two weeks of his session denouncing Truman for making them return to Washington. Did he ever get mileage out of that. This was the do-nothing Republican Congress. Any momentum the GOP had from its 1946 Congressional majorities was stopped then and there.

His opponent was Thomas Dewey, governor of New York State, who had run against FDR in 1944. In that campaign Dewey had gone for blood, demonising Roosevelt, slandering Eleanor, deriding each of the Roosevelt children by name, and even deprecating the pet dog, Fala. As one wit put it, the only thing that stopped him from stooping lower in vilifying every Roosevelt was the floor. Dewey lost, and decided to go at 1948 in a different way.

He ran as though he had already been already elected. He ignored the platform mentioned above, and spoke only in platitudes and generalities. His failure to emphasise the Republican platform gave Truman ammunition. The vagaries of Dewey’s speeches were such that the Truman campaign published collected excerpts from them to show that he had nothing to offer.

Dewey’s aim was to present himself as above partisan politics, while not making campaign promises that would later tie his hands. He was being presidential, he thought, acting as if he had already won, after all that is what the polls kept saying. He presented the smallest target ever. And he never once asked audiences to vote him, as beneath presidential dignity. While he, too, travelled by train he did not stop at every crossroad and give a talk, but moved from city to city to speak in hotels and auditoria. After he spoke, he did not descend from the podium to shake hands, but rather left by a back door. Even on the platform he exuded an icy aloofness that journalists reported.

In contrast, Truman explicitly asked for members of the audience to vote for him. In so doing, he sometimes directed this request to Republicans in the audience who had come to see if he was the fool being portrayed. He was always careful to distinguish Republican voters, who were ordinary folks, from Potomac Republicans in Washington D.C. The voters were just trying to get along and mistakenly thought sending Republicans to D.C. would help them do that. But how could it, he would ask, look at that do-nothing congress that had ample opportunity to enact its own measures for the benefit of the common man, but did not do so, because that was not really the goal. The goal was to win office, and then favour the vested interests of Wall Street, industrialists, and their kind. He hammered away at this theme, leading to that famous headline.

Restored to office, things went from bad to worse for Truman. The Berlin Crisis remained. There was an assassination attempt. China went Red. The Senate went witch-hunting. North Korea went south. George Marshall quit due to ill health. Never a dull moment. At this point I think I will give up summarising his presidency except to say it was action-packed. Just remember there is the Korean War, the showdown with General Douglas McArthur over civilian control, the vandalism of that Kremlin asset Joe McCarthy, and more.

Perhaps one point has to be made. Truman was adamant that the atomic bomb would not be used in the Korean War. Though there was much pressure to do so from the public, the army, the press, and the Congress, he steadfastly refused even to consider it. He, like any sensible person – always a minority in a crisis, was terrified of this weapon and kept it off the agenda. He could say honestly it had never been discussed as an option. Not even in the darkest hours when the Busan perimeter buckled. Though he made many decisions to act, this was perhaps his most important decision and it was not to act and he made it repeatedly.

He had made up his mind in 1950 just before the Korean Conflict started that he would not seek another term in the 1952 election, because by then he would have served just 82 days short of two full terms. That was enough for anyone, he concluded, and wrote in longhand a letter he kept in his drawer to be produced in the middle of 1951 in which he declared he was stepping down.

There are long chapters on the 1952 election with the reluctant candidate, Adlai Stevenson succeeding Truman as head of the Democratic ticket. Stevenson had the soul of a poet, not a politician, but in any event no one was going to best Dwight Eisenhower. Ditto 1956 when no one else wanted the nomination and Stevenson backed into it again.

In retirement the still sprightly, Truman moved back to Independence to the family home and devoted himself to memoirs, which are largely lists of meetings offering no insight into either events or people. He also turned his formidable energies to his presidential library. Though there is much discussion of the detail, this book does not give Truman nearly enough credit for establishing the concept of the presidential library. He had seen the way souvenir takers had carted off just about anything mobile from the White House when FDR died, from furniture to filing cabinets of papers. Truman had encouraged Eleanor to take whatever she wanted, and it turned out she wanted a lot because it had been her family home for more than a decade and she had proprietorial feelings. This observation was the seed that later came to fruition.

He lived thereafter on his army pension, as there was no presidential pension, and later a publisher’s advance for memoirs.

I have been to the Truman Presidential Library in Independence and a visit is highly recommended for president buffs. It certainly reflects the man, fearless, direct, and simple. While it was being built he pitched in more than once himself to the work (no doubt as relief from this memoirs), and insisted on some of the displays, like the piles angry and damning letters he got from parents of GIs serving, missing, wounded, or killed in Korea. Those families paid the price for his decision(s) and he thought they should have their say. He would take the heat.

Of all the things he said and all the things said about him, the one that I like best is his remark in this paraphrase: There are million people who are more qualified than I am to be president, but it has fallen to me and I will give it everything I have got.

The book reads like a novel, a thriller even, in its invocation of people, places, and events. I found myself on more than one night sitting up past my usual bedtime reading on and on, finding it hard to stop mid-chapter, and so not stopping. My practice is usually to switch off such serious reading in the evening and read a few pages of a krimi as bedtime and sleep beckon, but some books are hard to put down and this is one of them. It is easy to see why the Pulitzer Committee gave it an award. I have been through one other of his biographies, that of John Adams quite a time ago, with no particular memory of it, but that was the audible version while I was driving around historic utopian communities in the midlands, midwest, and upper south in days gone by.

* Who was the shortest serving Vice-President, you ask? Take notes for the next round of pub trivia. John Tyler had 31 days from taking the oath of office to when President William Harrison, just elected, died. Andrew Johnson who succeeded Abraham Lincoln had 42 days. William King who never set foot in Washington D.C. as VP died 45 days after taking the oath of office in Cuba. Then comes Truman.