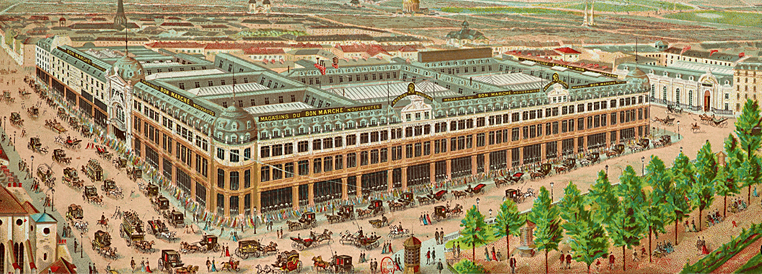

One of the oldest and biggest department stores in Paris is Le Bon Marché. To read a history of the origins, foundation, and life of this great enterprise I thought would be amusing, informative, and diverting. My imagination ran ahead to consider the nervous bankers who staked the first investment in this new-fangled idea. Then there was the genius who recognised the opportunity. Once a going concern I imagined the turf wars among its sections and ego conflicts among its personalities. The decisions about display, say for example, ladies undergarments. Over the years more than one cashier must have been tempted by the grisbi. I wondered what famous names had started a career selling hair brushes there, or in the back sorting stock for the shelves. Then there would be the customers.… Rich pickings for sure!

Yes, reading about that great ship, its crew and its passengers, sailing through good times and bad would be great fun and interesting. What a cast of thousands from slumming aristocrats to charlatans and grifters, provincial girls leaving home for the big city department store and accountants giving up private practice, the civic bureaucracy that would have to approve everything from construction to opening hours, to say nothing of the opportunities for kickbacks on orders, featherbedding nepotism in staffing, creative accounting and more. Then there would be the changing fashions in clothing, but also in plumbing and kitchens that a successful merchant must lead and follow. To stay afloat BoMac, as habitués once called it, must have been reinvented more than once: that means change, which of course also means resistance. The stories must be myriad.

‘Bring it on!’ I cried.

Regret followed immediately when I read the first chapter. Perhaps I should begin with a Content Warning. Beware! The book was written by a sociologist. In the name of discretion I do not enter the title of the book nor the name of the author.

In the first quarter of the book there is no sign of a human being. Instead there are structures and forces, movements and phenomena, masses and elites, classes and cleavages, times and tides, change and continuity, abstractions and concepts galore. It is likewise encrusted with caveats and qualifications that obscure whatever the point may be. This defensive, small-target approach exhausts the reader long before it enlightens.

No one makes decisions, no one makes mistakes, no one does anything – the gestalt does it all through its mechanistic extensions. There are no agents, only structures. Yes, a few names are named, but they are Sims not individuals with wills, hopes, ambitions, and other human cargo. They function as chess pieces on a chequerboard of sociological theories and concepts.

Was it Gerald Durrell who once described a jellyfish as a process? The fish is itself 95% water, immersed in itself – water. It is hardly (5%) apart from the water. To think of it as separate from water is to misconceive it. To abstract the jellyfish from water makes it meaningless, inert, in a word, dead. That image came to mind as I read this book, well the Kindle sample.

I could go on, and the author certainly did, but well it is not reading for pleasure and profit. If suffering from a toothache, this is a book to read because the concentration and effort it requires will take anyone’s mind off a dental pain…. Perhaps I should try Émile Zola’s novel Au Bonheur des Dames (1883) for some of this story, but I do not associate reading the didactic moralist Zola with amusement or pleasure.