GoodReads meta-data is 222 pages, rated 4.17 by 8,192 litizens.

Genre: historical fiction.

Verdict: Detailed and compelling.

It reads in good part like a study in leadership with much inner dialogue and very little of CGI shot ‘em action of the (trailers for the) film (Greyhound).

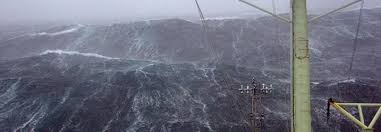

Convoy J45 of thirty-seven merchant ships crosses the North Atlantic in the winter of early 1942. There are troop ships from Canada packed with men. Enough fuel in five oilers to power the entirety of the Britain’s Royal Navy all over the world for one day. Food and medicine to keep alive thousands of the very young and the very old. There is also a boatload of women, volunteer nurses. The load is a weighty in every sense.

It is also varied. The merchants, liners, and oilers are Greek, Norwegian, American, Canadian, Dutch, Danish, Polish, and French. Each nationality must put aside its way of doing things and cooperate with the whole, led by a British ship. Accordingly, the signals (by flag and light) are terse and few. No complex manoeuvre or qualified directions can be given to such a polyglot assembly. Keep it simple!

By a quirk of enlistment dates, the senior naval officer is Commander Krause, USN. He has many years of preparation and is well trained and highly motivated, and completely inexperienced in the duty, to the North Atlantic, and with the new ship he is on, and unknown to both his crew and 3000 other men sailing under his command in the whole of the convoy.

His interior monologues in decision-making lay out the tactical and strategic chessboard on which each ship moves. We also learn along the way that Krause, despite his obsessive efforts, has been judged only an average officer and will not be promoted any time soon. He is a ‘C’ student who studies long hours, keeps notes, tries hard, is dedicated, and just scapes by. In war even ‘C’ students must serve.

Keeping the convey’s ships together in the cruel sea is almost impossible but absolutely necessary since stragglers attract U-boats. To herd the ships of the convoy and to protect them from U-boats Krause has two destroyers and two corvettes. His own ship, one of the destroyers, is the reeling USS Keeling, as the crewmen say, while the other destroyer is a battle-scared Polish ship that escaped Danzig. One corvette is British and the other Free French. Four navies working as one with four different sets of protocols, training, equipment, and attitudes. The officers of the four ships have been expected to learn and comply with a 259-page manual of operations for such missions in their spare time. It is, of course, in English and the French and Polish officers have tutors (liaison officers) to help them. The manual is a compromise written by a committee in London, and reads like it. There is no index.

The other three naval captains, his juniors in service, have been at war for more than two years and their crews have suffered casualties and the ships show battle damage. Yet he and the pristine Keeling are in command.

Krause is a serious man who is mindful of his own limitations and has devoured the manual in between sessions of meditation and prayer in the few minutes he has to himself. Those minutes are few. His dedication might compensate for his lack of ability and his lack of experience in these waters and convoy duty, the writer seems to imply.

The decisions, the assessments, the reports, the weather are all endless, relentless, and merciless. On the bridge there is a constant flow of information to which he must react. Radar and sonar are limited in the weather, and so are the six-man lookout watches in rubber suits, roped to their stations, drenched in ice water at every pitch, roll, or yaw. They can see things the radar and the sonar cannot see or may miss with so many other ships nearby, a periscope, a floating mine, an oil slick, a torpedo wake ten-feet below the surface of the boiling sea, a life raft; if they don’t blink; if the salt water does not burn their eyes; if the cold does not freeze over the binocular lenses.

None of this is good. The pressure, the friction, the potential for catastrophe are ever-present. Then it gets worse when the six-week trained sonar operator reports a positive return. Ping! Action is required this instant. Or is it? Sonar operators before the war were trained in twelve-weeks, and passed by scoring 9 out of 10 or better on three tests. In order to get ships crewed, that training had been cut to six weeks, and one test with a passing score of 6 out of 10. The same can be said of most of the rest of the crew from the gunners, to the depth charge mechanics, to the cooks, all of them half-trained and inexperienced in the North Atlantic.

Moreover, as Krause had silently observed since taking command of the Keeling some of them did not want to be there and it showed in posture, by intonation, and with looks. He knew that for all of them to survive, for the ship to complete its mission, everyone of them had to do his assigned duty completely and immediately. He knew that. He was not so sure some of the crewmen knew that. Well, they are going to find out now.

There follows a long game of hide-and-seek as the Keeling, with Krause’s lack of experience but that thick manual, tracks that sonar ping, which in time by its own manoeuvres proves itself to be a U-boat commanded by an practiced and cunning captain with a disciplined crew. While on the surface the Krause has many advantages, but the U-boat turns some of the strengths into weaknesses with tricks and feints. The Keeling is faster, but with a deke here causes it to overshoot and lose time in U-turning.

In the flow of data that is fed to Krause about the elusive U-boat, the Keeling itself, the other escorting warships, the 37 craft of the convoy, also comes – in writing – a Most Secret Signal from the British Admiralty that the radio operator hands him, because it must not be spoken aloud. A wolf-pack is definitely in the waters ahead. (This intelligence is the fruit of the Bletchley Park boffins and must not be revealed to anyone who does not need to know in anyway. After reading the message Krause orders the operator to destroy it by burning it in a bucket on the bridge.)

The tension of all of these proceedings is marvellous, and not a shot has been fired, nor a definite sighting of the enemy made, but the knowledge that he is there becomes an electric charge in the hull of the ship, everyone feels it. More decisions are required. How long can Krause keep his crew, and the others on the warships, at Battle Stations before they tire, lose concentration, become bored, and if nothing happens then come to be less responsive to that alarm in the future. At the same time the cooks want to know if dinner will be served. The radar officer says one of the screens has to be reset to offer more clarity and that means turning off the radar for two hours to change tubes. To turn it off deprives Krause of one of his advantages. To rely on its erratic dancing blurs that now fade in and out is also risky. The battering of the green water has loosened the forward chains, and they should be fixed, but that would require turning away from the gale-force wind, offering a target. So it goes.

The pressure on the captain will make him a diamond or crush him. That pressure cascades downward as the deck officers realise how high the stakes are and the importance of his own duty by the book. Similarly the bridge crewmen imbibe the gravity of the situation and it radiates from them through the whole ship. The increasing strain is palpable.

At every step Krause must be aware that to utter a sharp word or to ask for a repetition might undermine the confidence of a crewman and impair his efficacy next time. Always he must speak in a flat, level voice without emotion, haste, or temper. Always he must speak the approved navy phrases — deck talk — with no embellishments, for these could be misunderstood in this perpetual crisis, always he must speak with a dead calm to promote that same calm in others.

In the two days covered in these page Krause gives more than two hundred orders about navigation alone. Then there are other orders about search patterns, patrol assignments for three other ships in the flotilla, running repairs, meal service, and the like. He also communicates with the cargo fleet in the convoy. Try another metaphor: The stone he is made of is slowing chipped away by these decisions to expose the inner man.

The Kraut, as the crewmen call him, draws strength from his Biblical education with many well chosen homilies that remind him of eternity, that is, the bigger picture. Pondering some of these passages is one of the pleasures of reading this book. Rather than telling others what to do, this Christian tries with every conscious minute to live up to that faith’s highest standards, largely in silence.

Cecil Scott Troughton Forester did not serve in the Royal Navy either in World War II, still less the Napoleonic Wars of his 12-book Hornblower series. While he was born in Cairo, he left Africa at age five and never returned. He did write about thirty (30) other novels, of which this is his last. He also published another fifteen works of popular history.

Loved skimming the condescending comments on Good Reads. Always good to know the trolls are feeding.