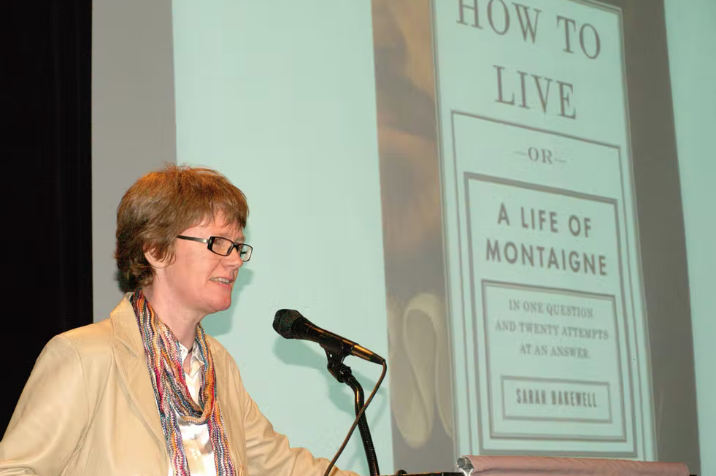

How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010) by Sarah Bakewell

GoodReads meta-data is 387 pages, rated 3.96 by 9260 litizens.

Genre: Biography

Verdict: Merveilleux!

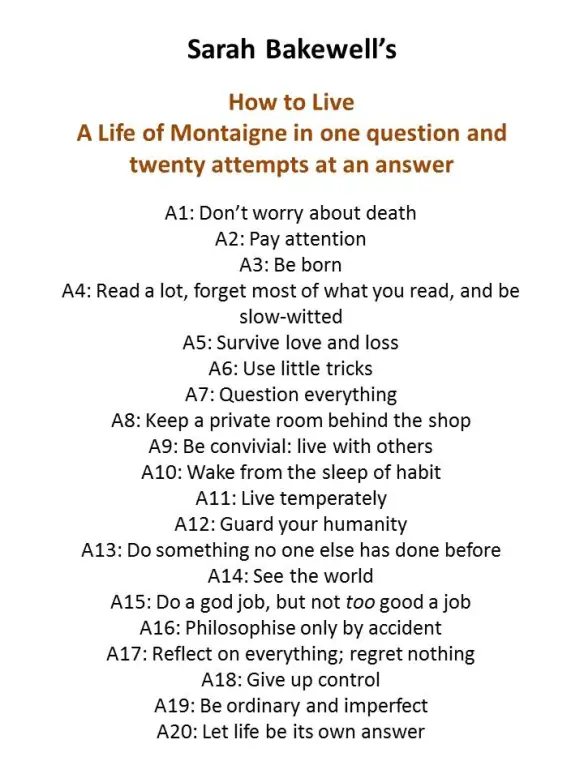

Michel Eyquem Montaigne (1533-1592), author of Essays, largely autobiographical. He is credited with coining the word ‘essay’ to refer to short written treatment of a single theme. After holding forth on subjects as diverse as vanity, certainty, torture, marriage, prayer, age, conscience, cripples, cannibals, anger, thumbs, sleep, liars, Cicero, clothes, nudity, early rising, he was likely to conclude by saying, Mais alors, que sais-je? or ‘But then, what do I know?’ Few of the essays stuck to the title topic, and wandered through digressions and asides in a conversational tone. Most were between three and nine pages in print. He was a blogger avant le mot. These were the fruit of his mature years, but how did he come to that point?

He had a hothouse upbringing even stranger than that of John Stuart Mill.

At birth his father had him then and there separated from his biological mother (the wife) and deposited with a wet nurse and her peasant family, where he remained for two years with no familial contact. Only on his second birthday was he taken home. According to his father this experience with the peasants was to imprint upon him an awareness of others.

Once he was home his father had decreed and arranged that everyone speak Latin. There was a tutor who was fluent in the dead language and he taught the servants, and his father a few Latin phrases to use to and before the boy. No one spoke French within his hearing. In this way, his father reasoned, he would learn Latin naturally as the Romans did. Latin was the language of the law, the church, the government, and the international language of the learned and that made it the bedrock of a successful career and life, reasoned his father, who knew no Latin until the tutor taught him a few phrases. By this time, his mother had other children and she ignored this eldest specimen child in his test tube.

On his sixth birthday he was sent to a residential boarding school sixty miles away where he stayed for ten years until age sixteen. He neither returned home nor was visited there by any members of his family, though there was the occasional letter in Latin from his father prepared by the tutor. It was only then at six years old that he heard French. While the teachers knew why he ignorant, the other students neither knew nor cared and were cruel in taunting and teasing him where he was nicknamed Michau. Having no choice, he endured it and says little about it in his autobiographical musings. At sixteen he returned to the home he barely knew.

His father hoped that these experiences would prepare his son and heir for life. He was not following any theory of learning, for he was himself uneducated and had a distant awe and respect for knowledge. Père Montaigne had filled his library with books he could not and did not read as totems for such learning (like the wall of unopened books behind Craig Kelly these days). He was an energetic member of the lesser nobility who worked tirelessly to improve his properties. However, he was better at starting projects – dams, bridges, retaining walls, weirs, levelling fields, clearing stones, fences, hen houses – than finishing them.

Michau became a magistrate (part notary, part lawyer, part judge) in Bordeaux when he was about thirty. Between sixteen and that age, not much is known of his life, though he learned to ride a horse and liked to do that. He did not like the duties of managing the property, and when his father died, most of those unfinished projects remained unfinished. As heir and owner he turned over management of the property to an agent, confirmed a complete break with his birth mother, and ignored his six siblings whom he barely knew. When he married he had a similar distant relation with wife and his own children. (There is an interesting explanation of the relevant manners and morēs of the time that is too detailed to summarise. Read it.)

He travelled to and from Bordeaux and was a dutiful magistrate, thorough, patient, insightful, and bored by squabbles over chickens. He wrote very clear briefs and rendered succinct judgements, which inevitably made him enemies because there was always someone disappointed at a result.

The work might have been boring most of the time but the times themselves were not. It was in the midst of the Troubles, aka a 60+ year war of religion among Catholics, Protestants, and variations of each. While the main fault line was Catholic versus Protestant there were factions within each so that sometimes they attacked their own. Three- and four-sided conflicts were common. One side would massacre several hundred of the other and retaliations would follow, until the blood lust abated and an implicit truce settled in. Then at an opportune moment, often when the victims were praying in a church, another slaughter would occur, and the dance of murder and mayhem in God’s name would begin again. God’s will, they shouted. (Starting to sound familiar?) Murdering defenceless people at prayer has been the practice in the American south for years. Still is.)

There was also an international dimension as Protestant England and Catholic Spain encouraged the conflicts in France so as to preoccupy it and reduce French influence in Europe. Consider contemporary parallels at leisure.

The city of Bordeaux, though a long way from Paris, was contested as a rich prize with claret wine, agricultural produce, fishing, and sea port, and one reason Montaigne resigned and went rustic may have been to opt out of this endless, murderous conflicts.

The Essays are not easy to read, though they are low key and can be amusing; they are also contradictory, vague, confusing, and stuffed with digressions and asides. Contradictions, there are more than a few. He says he is solitary and he also says he is sociable. He says he prefers books to people and he also says books are useless compared to a good talk with people. He says he is lazy and he also says he rises at dawn to read and write and spends too much on candles after sunset to keep reading and writing. He reticent and talkative with strangers in the same sentence.

Our author guides readers through the labyrinth of the stops and starts of Michau’s mental wanderings, often placing them in either his personal or historical context with a deft hand. The tone is informal and there are topical references to the contemporary popular culture. Most of these hit the mark. In none of them does the author try to supplant Michau, as some biographers sometimes do in shifting the focus from the ostensible subject to themselves. (See the comments on The King of Sunlight elsewhere on this blog for an example of this Me-ism syndrome.)

There are some fascinating insights in the Sixteen Century attitudes to sex and family that are best read. We are a long way from that time and place. But it explains his distance from his own family.

There are details, more than I wanted but which I perhaps needed, on the deadly influence of religion and Michau’s twists and turns to stay safe from condemnation from self-appointed, self-righteous apostles of one sect or another. One of his fears was that a Savonarola would appear and burn down the tower in which his library and cabinet of curiosities were housed.

Bordeaux was a Catholic city surrounded by a countryside of Huguenots. As a landowner and as a civic official Montaigne had frequently to navigate through these troubled waters. One of his principles was to get along with everyone, and he was pretty good at that. Though of course any time he was polite to a Protestant, a Catholic zealot would threaten his life, and any time magistrate Montaigne ruled in favour of a Catholic claimant, a Protestant fanatic would swear vengeance. In this climate conflicts over butterfly farms escalated. By and large Montaigne was more successful than many others at toning the conflicts down. So successful was he at it that he ascended to a higher office as mayor of Bordeaux in which office he was the first ever incumbent to be re-elected. He liked to say in later years that in his tenure nothing happened, and it took a great deal of work to ensure that.

All of these efforts at putting oil on troubled waters made his name known, and his nearest neighbour in the countryside began to cultivate him. That was Henri de Navarre, a Huguenot champion, who saw in Montaigne an honest broker to communicate with the Catholic court in Paris. In this vexed situation the Queen Mother, Catherine d’ Medici, became an active negotiator and Montaigne was instrumental in keeping a channel of communication open between her and Henri who was to became Henri IV. At times both Medici and Navarre offered Montaigne honours and positions which he steadfastly declined and ducked to stay out of the limelight.

Of Montaigne’s many aphorisms, one that particularly appealed to me was his advice ‘to have a room behind the shop,’ by which he meant a wise man (and yes he assumed only men as readers) would do well to have an escape room away from the public and his family, too, a room of his own. Thus he is an exponent of the Man Cave, as some refer to my private office. Montaigne recommended such a retreat as a place where everything is to your liking and no one else enters except by invitation. He trained a servant to clean the room in a way that did not disturb the papers on his desk, the piles books on the floor, the notes stuck to the walls, the curious oddments scattered on the shelves, and so on.

Another of his aphorisms was to stay at home: If you want to know about the world, read a book. But he was as inconsistent about this as about much else. His poor health became an excuse to travel, rather than lie at home. Off he went in search of water treatments, clean air, cosmic balance, a miracle cure, and snake oil unavailable locally. Once he started travelling, there was no stopping him. A two-week sojourn to a spa town two days away turned into a fifteen-month trip to Rome and back. At each stop he sent scouts ahead to see what was on the other side of the next hill, and as soon as they reported back, he had to see for himself, and so gradually he found himself in Rome. Along the way he filled his notebooks with interviews, sights, descriptions, drawings, and collected books and curiosities just like the tourist he was. By this time his name was known to the reading classes, and he was frequently feted along the way. He claimed to dislike this attention but always turned up when invited, the first to arrive and the last to leave. He spoke native Latin, fluent French, and a passable Italian so he was in demand.

Throughout his life he reworked the Essays in many editions,well, he added and added to the book, and it continued to sell well as it grew to three times its original length. He also violated his own rule of brevity and one essay is more than 250-pages long, with so many digressions and asides, not even this biographer can say with confidence what it is about.

The collection was also translated (and abridged) into English and Italian where new audiences found it. Over the years the Essays have been interpreted to death, the more so of late by the most dreaded of interpreters, Po-Mo PhDs in Cultural Studies. In the hands of some of these exponents the book has been taken to mean the opposite of what Montaigne said. The author skewers some of the most absurd of these sallies, though to be sure they are self-skewering, too. Reading her deadpan Stephen Colbert parodies of them is diverting.

She also charts Montaigne’s posthumous popularity among readers and intellectuals over the centuries with an amused eye. It is all in all a pleasant ride. Recommended.