Marc Wortman, Admiral Hyman Rickover: Engineer of Power (2022).

Good Reads meta-data is 328 pages, rated 4.33 by a scant six raters.

Genre: biography.

Verdict: compelling.

Young Hymie (1900-1986) was carried to the promised land in his mother’s arms, Russian Jews escaping Cossack pogroms to Ellis Island. How this five foot nothing, 98-pound weakling Jewboy (as he was frequently called, and worse) became a dominating force in the US Navy is quite a story. One thing is sure, he did not fall off a charm bracelet.

His father eked out a living in Chicago as a tailor while his mother cleaned up behind rich people on the Gold Coast of the Lake. No genius, the boy had his parents’ work ethic, and knew he had to make his own way. By some assiduous trading of favours his father got his son nominated to the US Naval Academy at Annapolis because it was a route to a free higher education. There was never any nautical motivation. After the nomination to a secure place he had to take a battery of entrance examinations, some contrived to exclude undesirable elements from the Navy, and he fit that category: small, working class, Jewish. He started with three strikes. The prejudice of the examiners and the examinations were his first exposure to the US Navy. He had expected nothing less, schooled as he partly was on the streets of Chicago, and prepared to the maximum so that he could not be excluded. Once in the Academy he experienced the bullying, racism, brutality, snobbery, anti-semitism, and stupidity he forever associated with the Navy, but he also discovered the engineer within himself. Engineering was working class and few other cadets showed any interest in it.

In his first sea duty on a WWI destroyer he spent all of his time taking it apart and putting it back together. He did not rely only on the blueprints, the gospel for most engineers, but rather went over the ship on and off duty, wrench in hand seeing how, why, and what worked, and soon learned that reality differed from blueprint. Soon he was making changes to increase efficiency. That DIY approach, and skepticism about blueprints continued throughout his career, even when he was an admiral inspecting an aircraft carrier, his ADC carried a wrench not a brief case.

Two qualities developed in his formative years. (1) The engineer who assumed nothing and tested everything, and (2) the officer who went full steam ahead at all times. He often made changes without seeking permission or telling anyone. He saw it; it needed doing; he did it. That got him attention and made him enemies. The efficiency reports by which careers are made or broken suited Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. He was a good engineer and an incompetent officer. He was also a workaholic who had no other interests. None. That lack of social life made him anathema in the Navy where a premium was placed on getting along with others, such a large premium that it trumped technical or tactical competence. (Ergo the miserable performance of the US Navy in the 1942 Guadalcanal campaign when the dancing officers failed to take the most elementary tactical precautions and paid for that in blood.)

His later sea duty included a battleship where he rewired the telephone system more or less single handed because no one would or could work with him and he was unable and unwilling to delegate, a submarine where he started thinking about alternative propulsion, a mine sweeper where he experimented with demagnetising mines, and so on. During this service he hated the cramped living quarters and the traditional schedule of four hours on and four hours off. Later he changed both these in the nuclear navy he created.

He was a loner, a martinet, foul mouthed, contemptuous of authority, and abusive of subordinates. Why he stayed in the Navy is one mystery, the other is how he stayed in Navy. As to the latter, there were guardian angels who wanted to keep good engineers in the service, and who were far enough up the hierarchy to influence that without having to suffer personal contact with him. As to the former, he was offered jobs in commerce more than once with a great deal more money but he never hesitated to say his favourite word, ‘No!’ He would never compromise on quality which he thought defined business.

He seldom wore the Navy uniform despite the standing order to do so, and that continued even when he was an admiral. His attire was either a business suit or a boiler suit. (See the cover illustration.) When he showed up for an inspection in a boiler suit, and he did do that, the captain of the ship to be inspected turned his thoughts to his retirement portfolio.

He worked in Navy procurement during WWII and dealt with contractors, designers, builders, quartermasters, and kept the fleet of thousands of ships at sea supplied, refitted, and armed. In doing that he rode roughshod over standard operating procedures, traditions, superior officers, the letter of the law, due process, and personal sensitivities. The enemies list grew but other guardian angels saw in him a capital letter Trouble Shooter who would boldly go where wiser heads would not tread and who could then break log jams that stymied other officers. He signed some 3000 contracts and insured by a rigorous, sometimes personal – remember that wrench – system of checking that all were honoured on time, on target, on budget. The Truman Committee singled out Rickover’s department alone for praise in its otherwise scathing review of Pentagon procurement in 1944.

One story in the procurement period brings home his way of doing business. This midget sat at a desk in a business suit, while two executives from RCA did a sales pitch on a new radio for the Navy. It was smaller and better than those in service, also products of RCA. They knew their stuff and spun a good line. One criterion for a radio was ease of repair in difficult circumstances. Putting an example of this new radio on his desk they demonstrated how easy it was to operate, after which he got up, and pushed the radio onto the floor. ‘Gentleman a five-inch shell just hit the bridge and damaged the radio. Repair it!’ They squawked, we are not operators. He rejoined, neither is the sailor who just pulled the dead operator off the set, but he has to use the radio to report the attack. Repair it!’

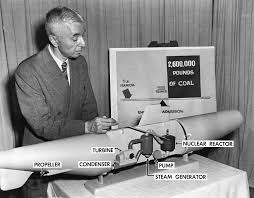

That was prelude. The payoff was nuclear. Signing all those contracts brought him into competition for resources with the Manhattan Project, and he became aware of speculations about atomic energy to generate electricity, and it came to him that it could be an alternative to coal, diesel, and oil. It was easier to say yes to him than to fight him, and he eventually established a Naval Reactor Project at Oak Ridge. First it had a staff of one, him. He schooled himself in nuclear energy with the same drive, determination, insensitivity, and – well – brutality that he did everything else. He worked twenty-hours a day, travelled far and wide to attend seminars and lectures, and to interview specialists. Having arrived late for a lecture on one occasion he bullied the home address of the speaker from a secretary who was working late, and knocked on the lecturer’s door at midnight demanding that the lecture be repeated for him here and now!

There was a bitter rivalry among the armed forces over who got the atom bomb, but when the Air Force hived off from the Army it was a foregone conclusion. Such a weapon in 1948 seemed to sink the Navy even more comprehensively than Bill Mitchell’s bombers. Who cares about ships at sea when there are long range aircraft carrying the Big One. In the scramble to maintain its relevance (budget along with careers), the Navy tried all sorts of gimmicks and one of them was nuclear power for the one ship that still seemed relevant, because it could hide from airplanes, the submarine. The Navy began pushing this project, and about that time the Truman Administration, President Truman himself conscience stricken about using the atomic bomb, though he would never admit it even to himself, was eager to turn atomic power to peaceful and constructive uses and nuclear energy offered him a chance to do that, so he backed the development.

No senior officer in the Navy thought a nuclear submarine was either possible or desirable, and so none of them wanted that job. Thus, Rickover stayed in place because no one else wanted it. The technicians involved also thought it would taken ten years to realise the concept but Rickover immediately cut that in half and promised a ship in five years. He delivered.

In the best tradition of McKinsey management as soon as the nuclear submarine was a reality, superior officers dismissed Rickover from the program he had created, masterminded, and driven. He had been passed over for promotion time and again, and when he was unanimously rejected a final time by the nine-man board of review, he was placed on the retired list. Such was the animosity toward him that when the first nuclear submarine was initiated in a ceremony he had organised, he was not allowed to attend. Only a direct and personal intervention by President Truman who wanted to met him put him at the platform. For this special occasion, he wore a business suit and not a uniform. Defying the order to wear the uniform on such an occasion of course added to his enemies.

Further interventions followed and he was promoted to Admiral in a rare split decision. The officers who knew him best hated him the most and they voted against him. Others realised he had to be promoted to save the Navy.

The USS Nautilus went to sea, setting off a bureaucratic battle in the Navy to crew it. The Naval Personnel Selection Board, otherwise known as God, selected three captains and decreed that Rickover choose one from among them. Leaving the decision to him was regarded as a great concession.

All were three candidates were Academy graduates, all were socially acceptable to the admirals club, all were experienced submariners, none had shown any interest in the nuclear propulsion. Rickover ignored the list and choose a submarine captain who was not an Academy graduate but who had risen to bridge, who was not dance party material, who had been passed over for promotion more than once, and who had been an avid contributor to the reactor program and knew how to use a wrench.

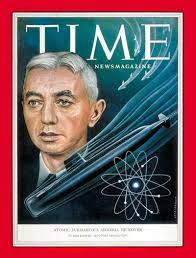

More ructions followed. Rickover was summoned to Washington to get an earful. He refused to go ‘at this critical time.’ It was always a critical time when such a summons appeared. By now he had been on the cover of Time Magazine as Mr Atom Power, he had been profiled on the front page of the New York Times for creating the Nautilus, he had been singled out by first President Truman and then President Eisenhower, and so he was well insulated. That, of course, only further enraged his legion of nautical enemies. Later when another forced retirement loomed an ex-Navy man, President John Kennedy, went to bat for him by holding the bill for naval appropriations until Rickover was promoted. Then Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter all supported him against the US Navy.

The Nautilus did the impossible by passing under the North Pole in 1958 which was as big a deal at the time as Moon landing in 1969 and a rejoinder to Sputnik the year before. When this feat was celebrated, the Navy insured that Rickover was not invited to the ceremony. However, President Eisenhower insisted on shaking his hand, and so he was permitted to attend but placed at the rear of the podium, and to prove how low the US Navy could go his wife was refused an invitation.

On another occasion when the reactor he built, some of it by his own hands, to supply electricity near Pittsburgh was switched on, the Naval Chiefs proposed that another, ‘better looking’ officer do the honours. Incredible, but it seems to be true. Rickover outmanoeuvred this sleight by inviting the president to do it, which he did.

While he made nuclear power possible he opposed with his usual belligerence and tenacity turning it over to civilians. He testified to Congress, he gave press conferences, he wrote books, he spoke at meetings in which he said that the commercial imperative would lead to compromises in safety. Contractors cut corners unless inspected with a wrench. Few materials are supplied to specifications unless there is constant inspection. Blueprints are no more likely to match reality than the plates in medical textbooks resemble a patient. He had been dealing with designers, contractors, builders for forty years and knew whereof he spoke, citing a myriad of examples to prove his point. The enemies list lengthened because many of the examples he cited involved the contractors now lining up to take over nuclear power.

The nuclear submarines, more than a hundred, and a few nuclear surface ships became known as Rickover’s Navy. He insisted that he alone select officers to crew these ships and he did that in his characteristically wilful manner. He sawed two inches off the front legs of the chair for candidates to sit on to make them uncomfortable from the start. He subjected about 15,000 officers to this test, and the many others that went with it, and so knew just about every officer in his navy, though he did not remember Jimmie Who. But Carter remembered him as a higher being, and made him a mainstay.

He also insured his ships offered each sailor a space and bed of his own, and an eight-hour shift. He also nagged Congress to fund a special bathysphere that cost more than a submarine to rescue crews from the deepest water. Members of the first subcommittee considering this proposal endured his midnight phone calls.

He stayed in the Navy, despite that ever longer list of enemies, for 63 years. He was one of four people to receive a presidential gold medal, until the Crook-in-Chief started handing them out to himself, strippers, drug dealers, ETs, and KGB agents.

A succession of presidents sponsored his renewal every two years until Reagan, whose Secretary of the Navy dedicated himself to forcing him out. He did not go quietly as President Reagan himself discovered! The implication is that the nuclear power industry wanted him gone and with him went a powerful voice for intense and constant regulation. Instead the Reagan Administration in this as in so much else, went for self-certifiction.

There is nothing in the book about either blacks or women in Rickover’s nuclear navy. Nor is there much about how he met and married his wife of forty years.

Perhaps the last word is that a Rickover reactor has never had an accident, while there have been dozens in the Soviet and Russian navies.