Hugh Trevor-Roper, Hermit of Peking: The Hidden Life of Sir Edmund Backhouse (1976).

GoodReads meta-data is 391 pages rated 3.90 by 155 litizens.

Genre: Biography.

Verdict: A curiosity.

An anodyne entry about Backhouse in the Dictionary of National Biography of Great Britain in 1970 described him as a sinologist, antiquarian, and businessman, longtime resident in China. That belied a very colourful life of a forger, confidence man, thief, confabulator, swindler, and traitor.

Scion of a wealthy Quaker banker, Backhouse (1873-1944) was a wastrel from the off, and his father refused to support him, though the title did eventually pass to the son, but not the dosh. By the way, the family pronounces the name as Back-us. To escape the collection agents come for the money he sailed for China in 1899, and fell in with the foreign ex-pats in Peking.

He had shown at Oxford (before leaving under a cloud of debt never repaid) a remarkable facility for languages and that was the mainstay for the rest of his life. As a student he learned French, Russian, German, Japanese, and started on Mandarin. He continued the latter along with Tibetan and Cantonese in China. Being poly-lingual put him in demand as a translator in Peking for Western journalists, businessmen, politicians, and others.

His modest manner masked as unscrupulous character. Hired to translate a Chinese document, say a contract, into German, he always insured the result said what the employer wanted it to say. If reality subsequently exposed the lie, he then claimed that the Chinese were at fault for changing their minds, and so on. He was plausible, Quaker upbringing, son a banker baron, lately of Oxford University, well-connected (he always claimed), impeccable in manner and dress with a diffident even obsequious manner.

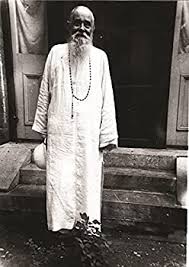

His authority as an expert on all things Chinese was confirmed as he went native in abode, dress, diet, and manner. He gradually withdrew from European society in Peking and lived like a hermit scholar (hence the title), emerging only when he needed some money. Like Jekyll and Hyde (or Bruce Wayne and Batman), he was one man but two people: a modest European and a hermit Chinese.

As a scholar he claimed to be friends with numerous, important political, financial, and social leaders in China, and at times to prove this, produced letters from them recommending him, praising him, and so on. These he always produced only when pressed for his bona fides. And they were always in Mandarin with his own translations attached and which he himself certified as genuine. At times a suspicious European would challenge these credentials, even once face to face with the Chinese who denied all knowledge of this man Backhouse, who then told the European that the Chinese was lying to save face, and he was so convincing that the European continued, to his later cost, to do business with him.

He became the agent for a major Clyde ship builder on the strength of his assertion that China was re-arming after the defeat by Japan and after witnessing the Japanese defeat of Russia, and would buy battleships by the score. He made a show of only reluctantly taking a retainer (which he then anted up by claiming he was entertaining court officials to grease the deal), and the ship builder paid and paid, and no battleship orders ever came, but instead his many promises that they would – for years, and thousands of pounds. Even at the time Trevor-Roper was researching this biography, the ship building firm was unwilling to cooperate with him by opening its archives to him. It surely was embarrassing to this firm for its stupidity to be aired in a book that its shareholders might read.

Then there were his exploits with Oxford University from which he extracted an honorary degree through a handsome gift to the library of a trove of rare and important Chinese books, scrolls, objects, and relics. This first gift was very valuable and genuine, leading to his name being incised in marble on a plaque in the Bodleian Library. After a suitable elapse of time so that it did not seem that he had bought his honouris causa by this gift, he got the degree. Later he contacted the grateful librarian at the Bodleian with the prospect of further additions to the collection, if only he had the money to purchase, pack, and ship the treasure. First it was to cost £500, then £2,000, and by the time the scam snapped it had run to £20,000. A few volumes did arrive at Oxford, but University scholars quickly ruled them to be forgeries. And that caused them to look more carefully at the first gift, with the predictable results. There was much dross interleaved with a little gold. Like the ship building above, Oxford did not want to expose its own foolishness, and kept the matter as quiet as possible.

Most incredible of all was a scheme he hatched to sell arms to the British embassy in Peking. When the Great War began, Britain was desperate for weapons and bought them around the world (until its own armaments industry began to manufacture in bulk). In September 1914 when this subject came up in conversation with an official Backhouse claimed he knew a Chinese general who would sell an arsenal. But he would have to be bribed and the arms paid for. In time Backhouse claimed to have located and secured the cooperation of a number of generals willing to sell vast quantities of arms – which he listed in detailed inventories running to pages and pages. But since this was illegal, he could not name any names or indicate where the arms were. Since it was illegal to steal government property and illegal to export arms, maximum secrecy must be assured so no one must negotiate and organise the purchase but Backhouse. Officials in the Peking embassy were determined to pull off a major coup by securing such a stock of weapons and in due course as much £2,000,000 was invested in the exercise. Well, no weapons ever appeared and most of the money disappeared. When confronted with the failure, Backhouse blamed the unnamed Chinese for welshing on the deal, and to save face the British officials swallowed that tale. They could hardly complain since the whole affair was illegal. Still less could they broadcast it to warn others off Backhouse.

He went on to an American Printing firm which wanted to print Chinese bank notes and pulled another scam on it. Again because of the questionable legality of some of the things done, no one could complain too much, too often, or too loudly.

The pattern is made abundantly clear by the author, and it is repeated at intervals whenever Backhouse needed money. Whenever things got out of hand Backhouse went to ground. He just upped stakes and left Peking for Victoria (on Vancouver Island, for the geographically challenged) or other parts. While visiting his family once, when subjected to some insistent questioning by his hostile brother-in-law, Backhouse went for a walk to clear his head and did not return to remain incommunicado for thirteen years. Some walk. He only resurfaced when he again needed a bolthole.

When the Japanese invaded China in 1937, despite being a lifelong Sinophile he became a cheerleader for the Japanese, who, in his eyes, were going to end Chinese corruption and restore the old empire – he took the puppet regime Japan had installed in Manchukuo as an example of that – and eradicate pernicious Western influence. Eventually, as an enemy national he was confined to a compound in Peking where he continued to declare his enthusiasm for the Japanese war effort even as Singapore, Malaya, Burma, and India were all attacked. One fellow internee said Backhouse volunteered to broadcast his support for Japanese on the radio, but the Japanese were not interested in this strange character in either his English or Chinese incarnations.

The last chapters concern a lengthy autobiography that Backhouse compiled in his dotage that details a fantasy life of grand, if grotesque, proportions. In examining the claims and assertions of these stories, Trevor-Roper begins to psychoanalyse Backhouse, because, to be sure, the question all along is ‘Why?’ Why did he forge when he could have made a perfectly respectable living as a sinologist, and at one point he was all but offered the chair of Chinese studies at Oxford University. It is pretty clear that Trevor-Roper cannot image why anyone would want anything more than that.

While a great deal of money came and went, very little of it ever stayed with Backhouse for he was once and always a wastrel. As fast as money came in, it went out even faster.

Some of the forgeries were undoubtedly done to get some cash, but that is no explanation for the vast effort and creativity he put into the major endeavours, like sixteen printed and bound volumes of fabricated secret diaries of a Chinese court official. Each volume ran to a million characters. That must have been hard and exacting work sustained over a long period of time. The conclusion is that Backhouse enjoyed dreaming of himself being the court official and writing the diary. That once he discovered this self-induced fantasy life he returned to it again and again in a bizarre instance of vanity publishing. That is as good an explanation as any.

That DNB entry has since been changed. See for yourself.

I read it as an example of how to research, present, and write a biography. It certainly makes use of an impressive array of materials, letters of contemporaries to others in which he is mentioned, company archives, embassy records, newspaper reports, and so. Some of which Trevor-Roper solicited by mail and which the source dutifully copied and sent to him. Oxford letterhead in those days seems to have worked wonders.