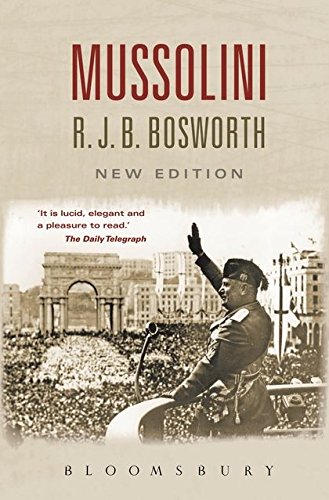

Mussolini 2d ed (2002) by Richard Bosworth

Goodreads meta-data is 584 pages rated 3.79 by 219 litizens

Genre: biography

Verdict: Measured, informative, and dense.

How did this itinerant contract school teacher from a backwater become Il Duce? Some of the ingredients to answer that question follow: he was accustomed to talking to audiences and writing as a teacher. He also moved around (albeit only in the middle of the peninsula) from one short-term contract to another and learned first some German and then some French. So far…so what? His assignments were in peasant villages and prior to the Great War, Italian socialism was rural and many of the milieus in which he taught were socialist to one degree or another. (Think of Ignazio Silone’s novels.) Young Benito was smart, ambitious, energetic, and social. He was literate and that soon saw him become a journalist for many small towns had their own weekly newspapers and many of them in his environs were socialist. He supplemented his pedagogical income with whatever they might pay, and from these came invitations to speak, and speak he did. (Though the author does not explore the point, I concluded that Benito loved an audience, a stager at heart.)

In that place and in those times, what did socialism mean? Improving the lives of those who lived on the land was the goal, but figuring out how to do that was puzzling. Easier to rail against the alleged powers that be and call for their destruction. The message was essentially negative, and… international. Socialism was the international brotherhood of workers (yet Italy then had few urban factory workers).

Then came the Great War and Benito, like many, but not all, others, shed the international skin and became a nationalist first and last, training his verbal guns on those wishy-washy socialist (like Antonio Gramsci) who were peaceniks because of the universal brotherhood of the working class. Mussolini, by the way, accepted induction into the army and served near the front, was wounded when a grenade exploded prematurely in a training accident, and hospitalised. The nationalism aroused by the War was partly irredentist to reclaim lands (Fiume, Trieste, Tyrol, and the other cites on the Adriatic Coast that had once been Venetian) from Austria, and those borderlands of the Veneto became a lifelong preoccupation with Mussolini. We travelled through some of this rugged terrain a few years ago.

After war, Italy’s territorial ambitions were not sated, and, moreover, the million plus returned soldiers were ignored by an impoverished and exhausted government in distant Rome. (Wherever you are Italy, went the saying, you are a long way from Rome.) They began to form self-help leagues (as the Ku Klux Klan started out to be) called Fascios and Mussolini became a self-appointed spokesman for one of these organisations, and began to meld several of them together with a torrent of words and anti-government vitriol. He came to the notice of Rome’s political elite and efforts were made to cultivate and co-opt him. Consistency was never a constraint for him, and he liked this attention, trimming his rhetoric. He was soon elected to the Chamber of Deputies where he led the Fascist bloc numbering about thirty among the six hundred. Though always irreligious he began to speak respectfully of the Church and the Pope. Always anti-monarchist he began to pay obeisance to the king. Always anti-Roman government he began to itemise its virtues.

In the immediate post-war years the Rome government had been unstable. There were three major factions jockeying for position, and within each of them more than one aspirant leader with a personal following. Among the Fascistas there were several other leaders whom Mussolini had to out maneuverer, in so doing he learned to read men, promising one an ambassadorship, another a subsidy to publish anything he wrote, still another the prospect of being ennobled as prince, and he simply outlasted others because he had no alternative, whereas they did. The wealthy baron could retire to his property. The industrialist went to the counting house. The aviator took to the skies.

The paralytic crisis of the government that occasioned the March on Rome was a result of the three factions blocking each other and closing down government; each faction was determined that neither of the other two should prevail. But an outsider might be expedient (and temporary) and members of all three factions began to see in Mussolini an acceptable interim prime minister. He was a mutual second choice for all three blocs. Commanding only thirty seats (of 600), none of the three major factions saw a threat in him. With this horde approaching Rome, the three party leaders stepped back so that the King could offer Mussolini the task of forming a government to put out this fire. By the way, he sat out the March in Milan. The march was largely organised like the 1932 Bonus Army March on Washington and 1936 Jarrow March in England by disaffected veterans. Photographs of Mussolini with the marchers were later staged. When thus he appeared it was as a peacemaker.

Neither in this biography nor in Deakin’s Brutal Friendship did I learn why Mussolini’s long tenure was never disputed, especially in the seventeen years before World War II. Nor did I notice any reference to assassination plots and attempts. All the smart, ambitious people around him seemed content to jockey for second or third place, and there was a lot of that as described in both books. And there were long periods when ill health and ennui drained Mussolini of interest in the job of staying on top of the slippery slope. But stay he did. That endurance might be the product of a well-oiled machine but I rather doubt that. Another possibility is that despite all the son et lumière of the regime, politics was game played by a tiny portion of the populace, a few thousand out of forty plus millions, most of whose lives were untouched by it.

Perhaps it should be stressed there was never an ideology in Mussolini, nor was there any ingrained anti-semitism. He had no grand plan apart from somehow Making Italy Great Again (MIGA). Most of rhetoric associated with that goal was negative about breaking with the past and being modern, the nature of which was never spelled out. In the years before he became PM he published the equivalent of sixteen volumes of newspaper articles, speeches and the like and there are no constant themes in them. He spoke, he wrote in many voices, chopping and changing with time and tide, ergo he stayed afloat, while many a consistent ideologue sank.

There are many contrasts to Hitler shown through the book. Of course, over time as the situation deteriorated Mussolini changed, but for much of his career he differed. He had interests apart from politics. Chief among them were women and sports. He played golf, rode a horse, skied, walked vigorously for exercise, ate meat, and took the air on beaches when that was possible. He liked to drive a car himself, preferably open-topped on a nice day, while his appointed driver sat in the back with the body guard. He doted on his first born daughter. Took time off work when dictator to sit at home for a week with another sick child. At the office he was business-like. He worked at his desk, listened to reports, and often followed the recommendations of bureaucrats. His regime was more inclined to send enemies into internal exile (see Christ Stopped at Eboli by Carlo Levi) than to murder them, though that did happen (see The Conformist by Alberto Moravia).

In contrast Hitler had nothing but politics. Moreover, he was erratic, often rising late, ignoring the papers on his desk, seldom listening to or heeding the advice of others, like generals, obsessed by Jews, Bolsheviks, gypsies, Slavs, and countless other real and imagined enemies nearly every waking hour. Meetings often consisted of his monologues with no specific directions, programs, policies, or orders. On other occasions he talked about the weather and not the agenda. Subordinates, that is, everyone else, were left to act in conformance to the generalities he had spewed out, and those that did were later praised, promoted, and rewarded.

The word ‘charisma’ is used in the text but unexplained. Its seems to mean merely personal rule. Although the fascist propaganda machinery no doubt endowed Mussolini with the attributes of charisma, but the signs and wonders were few and far between as the years stretched on and on. Things were accomplished during his tenure but the author does not deal with the draining of the swamps, the running of railroads, laying of roadbeds for agricultural produce, the dredging of harbours for the fishing fleet, or other such humdrum matters of government.

It is – what is the word? – pathetic to read of Mussolini’s meetings with Hitler, of which there were several. The early ones were marked by polite and ritualistic exchanges. Later during the war they became Hitler rants, with Mussolini barely having the opportunity to speak. From say 1942 in these meetings, Hitler lectured and Mussolini put on a blank stare, and nodded from time to time. Still later when Fascists zealots began an Italian version of the Holocaust, Mussolini mostly dozed, letting it happen. See Primo Levi, If This be Man (1987).

There is little discussion of the so-called Italian Social Republic of the last days established at Salo, and nothing about Mussolini’s efforts to secure Italian borders when the German Army in Italy surrendered. Deakin in The Brutal Friendship says that in these last, dark days Mussolini made several trips to Ticino in Switzerland to try to negotiate a German surrender that would retain Italy’s northeast border. Thus he took personal risk for what he perceived to be the greater and lasting good of Italy. It is hard to imagine Hitler doing something like that.

On another point, it was news to me to realise that Mussolini tried to prop up Austria before the Anschluss as a buffer against Germany on the assumption that Austria was too weak to reassert its historic border with Italy, but a resurgent Germany would do so. When Austria was devoured, the next alternative was to befriend Germany and try to direct its ambitions elsewhere. Strange but true.

Mussolini had a painful ulcer for more than twenty years and with the stress of the circumstances it grew more and more painful, distracting, and enervating. Regarding this illness the book demonstrates a fair-mindedness showing the reader Mussolini the man without exonerating him of any of his crimes by commission or omission. The book also shows us the author’s pointlessly large and obscure vocabulary. I read it on the Kindle and looking up the oddments was easy, but pity the reader of the paper book.