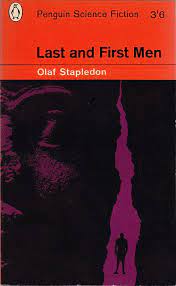

Olaf Stapledon, First and Last Men (1930)

GoodReads meta-data is 246 pages rated 3.79 by 5,465 litizens.

Genre: SyFy

Verdict: The history of the future

These pages offer a tour de horizon of a five-billion-year history of seventeen human species from the First, homo sapiens (that’s us), to the Last who watch Sol die and they with it. In between all manner of men evolve and disappear to be replaced by another lot. Along the way there is a viral invasion from Mars and the colonisation of Venus. It is a novel without drama, without characters, and without a narrative that has a start, middle, and finish. The story of Earth is told with a nearly divine detachment by The Last of The Last Men. It will remind some of those sociological studies where social forces, cleavages, structures, and other abstractions push us Sims back and forth.

In evolution through the billions of years, the Last Men can project their thoughts backward in time, even to some among the First Men. (That, by the way, is the explanation for visitations, ghosts, angels, saints, martyrs, messianics, charismatics, nutcases, UFOs, aliens, ETs, and other inexplicable often unseen things, events, and occurrences.) This projection without Blue Tooth is difficult, incomplete, and subject to distortion, like using the NBN in 2022. However among the Last Men some have perfected this projection so that this book can be dictated by the Last of the Last Men to a nameless receptive First Man of 1930. (Would such an ability to inhabit the mind of a subject make a Last Man the perfect biographer?) This future influence on the past reveals that the relationship we call time is lateral, not linear.

Between the First and Last Men are billions of years and seventeen (17) species of Men. Succeeding species develop as giant brains in jars. Others grow to twenty feet in height. Then there are the ones that sprout wings and take to the air. With each evolution there are cultural and moral changes, too. Though some verities remain, like jealousy, envy, bad will, selfishness, and McKinsey management.

The beginning of the book forecasts (though it is told in retrospect) the future of we homo sapiens, and it is all too believable. Stupid wars, avoidable virus plagues, anticipated but neglected climate change, personal vendettas that escalate to planet-wide wars that kill off half the population, denial of undeniable facts, and so on. It reads like BBC World Service reports this week. Move over Nostradamus, there is a contender.

Of women, first, last, or in-between, there is none. There is plenty of troll-food in the many, necessary generalisations about peoples and places. Check out the sanctimonious comments on Good Reads.

For his day job John O. Stapledon (1886-1950) lectured in politics at Liverpool University. That work left him, we must conclude, plenty of time to write as this was just the first of his dozen novels, all SyFy. (Did these count in his annual Research Impact Statement?) Others include: Last Men in London (1932), Odd John (1935), Star Maker (1937), and six more. The books sold well but reviewers, unable to categorise them, did not like them. Thus is creative writing denigrated by the gatekeepers of creative writing.

Although it is nearly lost in the giga-historical details that crowd onto the pages, the core idea is that of influence from the future on the past. That reminded this reader of Chris Marker’s haunting short film La Jetée (1962). There are some similarities though the execution is completely different.

There is a 70-minute film inspired by Stapledon’s novel which I can find only on Blu Ray and that does not interest me. I cannot find it on DVD. If someone can, please let me know. My cursory research into converting Blu Ray to another format left me confused. One guide offered a four-step procedure that involved about fifty steps, grouped into four categories. (Reminded me of the Man in Seat 61’s claim that the train from Amsterdam to Prague stopped only twice, whereas in fact it stopped nearly a dozen times. It all depends on definition.) The surrounding images are from the film.

I happened to see a reference to this novel in something else I was reading and that sparked my curiosity. I could not remember having read it (though I knew the author’s name and felt certain I had read something by him) so I found it available on Kindle and hour later and started to read it. At first I could not put it down, but as clever permutations piled one on top of another, going – as far as I could tell – nowhere except to the next page, I soon adopted the Kindle flick, reading only topic sentences. Fortunately, Stapledon learned the craft when a topic sentence was a topic sentence and that eased my speedy navigation. He is reported to have said that he turned to fiction for a wider audience than academic writing (and yes, he did a good deal of that, too) had. Strong stuff, those wider readers if they marched through several volumes of this detail.