The Professor and the Parson (2018) by Adam Sisman.

GoodReads meta-data is 256 pages rated 3.40 by 273 litizens.

Genre: Biography.

Verdict: [Gasp!]

Robert Michael Parkins Peters (1918-2005) bested King Henry VIII in having eight (known) wives, and he was more efficient, at least thrice skipping the divorce before marrying anew. Three times a bigamist. His names and dates above are estimates since he used many names and many dates of birth. It may even be that he managed by occult means to lie about the date of his death. That would be consistent with his character.

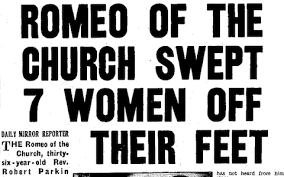

From the mid-1940s Peters made his way in clerical and academic life by lies, forgeries, thefts, and plagiarisms spiced with bigamy, deportations, jail terms, and all those wives. That later supplied the media hacks with headlines off and on over the years, but nothing, nothing at all, stopped him. And it seems it was no one’s job to eradicate this blood sucker. His determination, perseverance, ingenuity, audacity, and creativity are a marvel equal to the trail of destruction he left behind.

He continued despite setbacks partly because no one could quite believe he was doing what he did, and the more blatant it was, the more incredible it seemed to any nearly normal person. His life was a work of fiction which he wrote every day.

Moreover, he had some skill in picking his victims, often a dewey-eyed churchman who could believe no wrong of him, a headmaster desperate for staff, or a women in want of a husband. Yet there were other churchmen and other women who should have known better and who were slow in grasping the reality of his criminal endeavours. There were also many academics, from professors to deans, who took his bait whole, and regretted it.

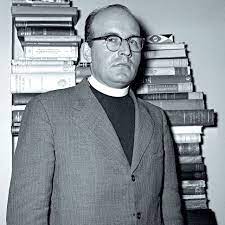

To avoid creditors, to avoid warrants, to avoid his own past he moved back forth among England, Scotland, Wales, Canada, the United States, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, and South Africa. In each country his persistent and energetic efforts netted victims. He also made use of many aliases by shuffling around the four names above. But his ego never let him avoid a photograph so there are many that show the man with many names.

What were his crimes? He forged letters of recommendations, diplomas, transcripts, credentials, and passed more than one dud cheque. He took money for tuition from naive students to teach them subjects about which he knew nothing. He claimed his instruction was accepted for admission to schools and universities when it was not. There were persistent and recurrent suggestions that he forced himself on young women in the girls schools where he was supposed to be teaching. But again it seems to have been no one’s job to sort that out. He plagiarised the work of others and published it as his own, and if confronted with the facts, tried to claim it was the other way around despite the dates, evidence, and facts. That is only the beginning.

He also masqueraded as a preacher and a priest and was so convincing he gave sermons and officiated at weddings, which because he was in fact unlicensed, were invalid. Not forgetting the bigamies.

More than once a bookstore proprietor was defrauded when Peters would open an account, claiming to be a lecturer at an Oxford college, say, and take any number of books on credit, sometimes by the box-load, never to pay the bill. When the proprietor contacted the college it was to discover that he was unknown there. These bills were measured in the hundreds of pounds.

He gained employment more than once in a clerical or an academic position by forging degrees from Oxford, London, Liverpool, Manchester, and elsewhere depriving other qualified candidates of the opportunities. Invariably he was unable, and sometimes unwilling, to perform the tasks for which he was employed. His longest tenure in this account is eighteen months, and most were a few weeks, or less. Some only a few days. His stay at a school in Sri Lanka was shorter than the sea voyage to get there.

Then there were the wives whose ranks grew over the years. In the many photographs he seems to be balding, middle aged man with spectacles, but he must have had something. One of the early wives, Sisman supposes, wrote the only sensible thing Peters published, while others funded his forays. These women were secretaries, school teachers, civil servants, and all victims. Some stubbornly stuck by him when the consequences caught up with him, until he walked out on them for another.

His approach to courtship was direct, and if rebuffed he turned to the next in line, as it were. Likewise, when he passed himself off as a churchmen he went at it head on. He would appear at a Bishop’s palace, ask for an interview, introduce himself as the possessor of many degrees and licenses, and might even modestly show a letter of recommendation (he had composed the night before) from a respected authority. He set about making himself useful and secured a sinecure, until the balloon burst, say, when another churchman recognised him. This recognition occurred because he often revisited the same locales.

For the academy it was much the same with the variation that he would attend a conference in medieval history and in a question period rise to speak, introducing himself as Dr Peters of Magdalen College, after first having ascertained that no one from the college was at the conference, and pose a simple question that would allow him to follow-up privately with the speaker thereafter. In that later conversation he seems usually to have made a good impression and he would shyly allow that he was unhappy in his current (imaginary) position and could be persuaded to move. If he got a bite, then he closed the deal. If not, he went to another conference session and repeated the act.

There was no great artifice in his deceptions. The forged degrees were poorly done but no one seems to have noticed at first. When he applied for a post and submitted fraudulent letters of recommendations both the application and the three letters of recommendation were written in same handwriting, but this passed unnoticed. He was so oblivious that he made one such application to an Oxford college, which was rejected, and then applied to the same college again a few years later and was accepted. No one noticed that he had applied before and been rejected because the application was suspect. In each case the application and all the letters of recommendation were written in his own handwriting with badly forged documents.

In other instances he got appointments to schools, colleges, and universities on the strength of interviews, and no paperwork, neither transcripts, diplomas, nor letters. It is hard to feel sympathy for those who do not take the most elementary precautions.

One of his recurrent gambits was to set himself up in a rented house as a school of theology and then seek articulation with a university, meaning that completion of his program would be considered adequate for admission to the university. So desperate are some universities for fee-paying students that they will say yes to any such articulations. To be sure, Quality Assurance (QA) must be satisfied and often it consisted of Peters writing up a curriculum and sending that in. It would be approved. Then Peters could claim with a slight bit of truth that the course he offered was accredited by a major university. Seeing the crest of a well-known university on the wall of his establishment, the naive students, never many, but always some, would pay him a fee so that he could strut around calling himself Dr, Professor, Dean, and Principal to this audience, often in clerical vestments or an academic gown.

He did this half a dozen times and only once did a university bother to check on the reality behind the paperwork to find…nothing. That sounds like QA, all right, all paper covers rock, no scissors.

He tried to avoid confrontation with his victims or people who knew his past, but if confronted he either (1) cried foul, that he was the victim, or (2) threatened litigation. At the least these tactics gave him time to abscond one scene for another.

Generally, many took his baits, but there were even more others who did not. Women who rejected him instantly. Institutions hiring staff that did not go as far as an interview. Submissions for articulation that were denied prima facie. But they are not featured in the stories of his crimes told in these pages.

There are many gaps in the story as Peters went to ground, moved around, and changed his name yet again. In these gaps there were likely to have been further crimes and perforce other marriages.

One omission from this account is how Peters managed to stay out of the army during World War II. But he did.

We know all of this, and much more, because he came to the notice of the scourge of confidence men and tricksters, until he himself fell hard for one, Hugh Trevor-Roper, who loved kicking people when they were down, and who over the years, having met Peters in one of his early incursions to Oxford, kept a dossier on Peters’s adventures, and solicited reports from others. This dossier in its many box files became the basis for this book.

(It is likewise hard to feel any sympathy for his Lordship’s own fall, he who specialised in ruining the careers of many others with his savage reviews, assessments, and vitriol. It seems somehow appropriate that the fictitious Hitler Diaries got him. There is a discussion of this sorry episode elsewhere on the blog reacting to Robert Harris’s book on the subject. That is another instance of a fraud so simple, so blatant that the only explanation of its success is the will of those deceived to be deceived.)

Speaking of explanations, what explained Robert Michael Parkins Peters’s many deceptions? It was not money. He seldom made more than a subsistence income and not always that, often relying on a wife’s salary and savings. But he did revel in the status that his fantasies gave him. He puffed himself up and insisted on being addressed ‘Reverend’ or ‘Dr’ or ‘Dean’ or ‘Principal’ as he moved from one dreamworld to another. Of course, with a modicum of ability and application he might have earned that kind of status in the normal way.

Perhaps once he started his fabrications and at first found how easy it was, they became a habit, though they got harder as he acquired a reputation, a police record, a list of victims, for Lord Dacre was not the only one to keep a file on him, though Dacre’s was called a dossier as befits his Lordly status. Even if it got harder, lying was all Peters knew how to do so he kept at it. Regardless of Peters’s many victims, his frequent crimes, his recidivism, his disregard for others, his rumoured sexual aggression, his frauds, his theft, his serial exploitation of lady wives, his defrauding of naive students, there was no one responsible for containing him. He was convicted for one bigamy and served six-months in jail, and once for defrauding a bookstore which landed him in the nick for a few weeks, but mostly his victims were left unsatisfied.

Buried in a textual footnote near the end is the author’s remark that many people, upon hearing something of Peters’s story, have remarked that it could not happen today in the age to the internet. Sisman demurs, suggesting that people are tricked this way and that every day. The evidence of the truth of that suggestion is readily available. After reading this book I went to ride the exercise bike at the local gym in front of a television screen where Dr Phil was interviewing a woman who admitted to giving $US 900,000, amassed from her life savings, selling her home, and borrowing money from her adult children, to a man on the internet who claimed he loved her but whom she had never met, and never will since he is fictitious. Go figure. (Victims seem to be a regular feature of Dr Phil.)

Truth can be stranger than fiction, because fiction writers usually try to be credible where life has no such restraint. Then there is the ease of forging documents with computers these days. Consider all those fraudulent web sites and emails that look just like the real thing.

In the final chapter author Sisman suggests Peters is an example of the psychosis known as the narcissistic personality. Reading the list of characteristics that comprise this disorder certainly describes him, as well as the recent Thief-in-Chief. However, labelling is not explaining because that does not tell us how and why he got that way and stayed that way.

On Lord Dacre see the passages about him Ved Mehta’s imperishable Fly and the Fly Bottle (1961).