Of Beards and Men (2015) by Christopher Oldstone-Moore

Goodreads meta-data is 352 pages rated 3.65 by 165 litizens.

Genre: History.

Verdict: Occam did not do it!

Tagline: Male-Patterned History.

To beard or not to beard, that has often been the question. Whether it is nobler, sexier, scarier, holier, smarter, easier on the skin and chin to have a beard or not to have a beard. Or just more manly to be bearded.

In answering these momentous questions, men have turned to god, to science, to politics, and to women. They have also cast sidelong glances at each other.

If god gave us beards, then we are meant to have them, that is one recurrent school of hirsute thought. Another is that shaving is an act of obeisance to god. Is the beard natural, or a penalty for the fall from Eden? And so it goes. Priests have promoted conflict over this divide for millennia. Even the peace-loving Amish have fought over this question though the most persistent and violent these days seem to be the rabbis and imams.

The science is no less mystical. The beard has been related to – sit down and brace reader – sperm, muscles, and brains by hundreds of savants. Autodidacts like Caesar reasoned that when he was going bald on top, if he pulled out all the other hair on his body starting with his face, the hair would grow back on his head, so he plucked away, including [use your imaginations]. Dopey, yes but no dopier than many scientific explanations, see the reference to sperm above.

Just when scientists settled on one explanation or another for face hair, an adventurer would find nearly hairless indigenous men in the New World or apes with hair everywhere except faces to say nothing of bearded ladies. The wheel of explanation had to be spun once again, and again. Hygiene came into the question in the Twentieth Century. Did the beard harbour germs, parasites, or illegal immigrants?

Adolf Hitler, an exponent of the moustache, experimented with several different looks early in his career. The walrus moustache of a Bismarck was out, identified with the long-ago past. The spiky moustache of Kaiser Wilhelm was out, being identified with defeat. To be clean shaven was a sign of modernity, discipline, and the future to be sure, but the moustache yet retained a certain martial quality that he wished to evoke. Advised by his lifelong bromance and sycophant Joseph Göbbels, Hitler settled on the toothbrush mo. That toothbrush moustache more or less died with him. No one else wants to recall him, evidently, for not even dedicated Neo-Nazis can be seen with one. His mo is now identified with failure, too.

Although he was moustachioed, Hitler decreed his followers, including the army, be clean shaven modernists. Face hair was regarded as Jewish, Bolshevik, Slavic, or Gypsy. Not good. After the Night of the Long Knives, no other Nasty sported a mo. That shave was final.

Those Bolsheviks grew and shaved sideburns, goatees, beards, mono-brows, and moustachioes to elude Czarist police. No disguise could protect them from each other.

Stimulated by some primal memory of ferocious cavemen, generals have sometimes concluded that a bearded soldier is more frightening than a shaven man, and ordered the troops to grow a beard. Regiments of Napoleon’s cavalry were so ordered, with the further specification that the beard be long, glossy, and black. Not every horse-soldier could meet this standard and the entrepreneurs descended with black wax, false beards, and beard extensions that could be stuck on for parades and inspections. One regiment of the French Foreign Legion continues that tradition.

Later, shaving became a sign of military conformity and discipline. It was also an indication that the soldier had been near soap and water to keep clean. Though even then generals themselves often kept at least a moustache to evoke the primitive warrior.

Side Bar: In many creature feature films the monster is usually hairy. Are there any smooth-faced monsters on film? Submit answers below.

When King (1824-1830) Charles X in the French restoration turned the clock back to before the Revolution, the resurgent Catholic hierarchy, thrilled to be back bossing others around, ruled that shaving was god’s law. This edict was largely a reaction to all those bearded Protestants in the North. Chas X was hard to take seriously and soon on the Rive Gauche, in the student quarter (where I once lived for six months), it became an act of defiance to let it grow. Royal police arrived to fine the hairy, who then appealed to the courts. One case turned on the definition of a beard, for the defendant claimed he had forgotten to shave, been too busy to shave, had broken his razor and that stubble was not a beard when it came to paying a fine. In the modus vivendi that followed moustaches were accepted. They sprouted all over the Left Bank, and have recurred with each new generation of self-styled protestors. A similar story played out in the 1960s Stateside, during the Vietnam War. Hair everywhere was the norm for many against the army buzz cut and sub-dermal shave.

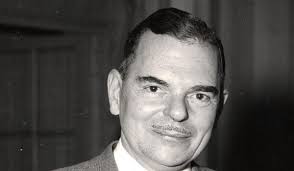

The last U.S. Presidential candidate to sprout face hair was…? New York Governor Thomas Dewey in 1948. He had a pencil moustache that was much discussed, especially by women. His wife proved exceptional in that she liked his mo but most others, as questioned by pollsters seeking the big news, did not. His mo was subjected to the intense and trivial attention that journalist still reserve for women, as when it was international news that the leader of the French Socialist Party appeared at reception in D.C. in flat shoes. Quelle horreur! Both French and American media had a feeding frenzy on that.

The last president to be furry? Go on, guess! Howard Taft (1908-1912) and his immediate predecessor Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1908). If a moustachioed Clark Gable had run for office, well he might overcome the hair barrier.

Mrs Dewey is not the only woman to rule on beards. Psychologists, social and not, have conducted endless experiments to see if a beard makes a man more or less attractive to women. As with much such research, the permutations of method are ingenious and meaningless. Our tax dollars at work. As with all social science the results are yes, no, and maybe.

There are also a few words on the carefully curated, meticulously cultivated Hollywood stubble look. It is a kind of a peach-fuzz version of the aforementioned Clarke Gable. (Gable, by the way, shaved his moustache and joined the Air Force in 1942 where he flew combat missions. He had no need to prove anything with a mo.)

The high priests of the gay fashionistas have ruled and misruled on face hair ad nauseam.This is followed by the rabbis and imams ruling on beards which is told in piteous detail. Like Hotspur they summon, but….who cares?

The book ends where I began. The return of the cheek fuzz today is an effort to assert manhood in an age when gender roles have been questioned, changed, made fluid, or otherwise challenged. The one thing a man has left to mark and make him a man is a beard. Pathetic I know, but that makes sense to me.

I had hoped for something about the evolution of shaving from dry blade to the micro-electrics today.

I wondered if Montesquieu had anything to say about beards and climate, but not enough to look for myself. Likewise the effect of the mass armies of 20th Century, setting the norm to shave in the name of hygiene.

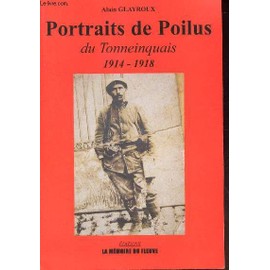

In the French Army a grunt is called a ‘poilou,’ a hairy one. Explanations for its origin are vexed. One is that the mass conscription of World War I cleared the countryside of men who sported bushy mo’s as a token of masculinity like the stubble of today. The printing presses of the era spread the image and word far and wide. Another takes it back to Napoleon’s hussars who were as hairy as Twentieth Century hippies. Think Abbie Hoffman on horseback with a sabre. Scary, right?

Occam’s razor suggests that there was little shaving in the trenches. Whatever its figurative origin it became literal there.

I read this in the hope of finding out something about beards in Renaissance Italy of Machiavelli’s time. There is a reference that I will follow up but nothing in this book bears on my interest.