The Library: A Fragile History (2021) by Arthur der Weduwen and Andrew Pettegree

Good Reads meta-data is 518 pages rated 3.84 by 987 litizens.

Genre: History.

Verdict: The new is old.

Tagline: Where’s Melville?

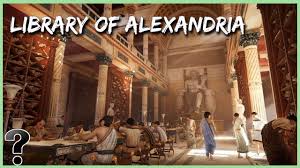

A comprehensive survey of book collections from Alexandria – both ancient and contemporary – to digital. Along the way is papyrus, vellum, linen, paper, and pixels.

Books have always sparked conflicts by those looking for a fight. Romans were one of the few conquerors who preserved the books of the vanquished for a time. Of course, these books were scrolls on papyrus, which is very durable, but burns easily and most of what they saved was in fact later lost in the convulsions of Roman history.

There is always someone who opposes change. When Greeks began writing plays on papyrus, Socrates decried it. By writing things down, we no longer have to remember them and that will weaken our brains. Ergo the smartest people had an oral culture. Aborigines know that.

When Gutenberg’s printed books began to appear alongside handwritten manuscripts, Erasmus, among others, decried it. Printed books were not invested with the effort, the grace, or the artistry of manuscripts.

Priests and kings decried printing because it put books, including Bibles, into the hands of too many people without religious, social, or political censorship. That undermined both theological and political authority. Books are like that.

When e-Readers came along in the 1990s it was the same story, and still is. (We got our Rocket e-Books long ago when Bill Clinton was president.) Many today refuse to use a Kindle or any of its cousins because… [some reason or other].

Then there were the wars over what is in the books. When Martin Luther kicked-off the Reformation, he also toppled many a library. Catholics purged monastery libraries (these being the main book collections) of Protestant-sympathetic items, and commanded their faithful among the book-owning aristocrats to do the same. That was the first shot.

Protestants replied in kind. When Henry VIII closed monasteries their libraries were purged, i.e., most books were burned. Henry also sent scrutineers around the countryside to find books in the private homes of the wealthy reading class and purge them. Closet Catholics hid offending volumes in priest holes.

This went on for a hundred or more years. More than one reader, more than one printer was murdered (executed) for possessing forbidden books by Catholic and by Protestant authorities doing God’s will. Sure. Happy in their work.

Another skirmish concerned books (printed or manuscript) versus pamphlets, posters, coffee house sheets, newspapers, cahiers, and other ephemera. One of Christopher Columbus’s sons became an omnivorous book collector and he gathered everything on paper and then bound the leaves like books. The result is a social record still used by researchers today. Whereas when Thomas Bodley put up an enormous fund to build a library for Oxford University he forbid it ever to hold such trivialities. Sniff. Sniff.

In the Nineteenth Century as literacy increased and the cost of making books decreased, then another front was opened in this culture war. It concerned the printing, distribution, and availability of books as the public library slowly emerged. The first fault line was non-fiction versus fiction. Political authorities, social influencers, respectable investors wanted only pious, practical, uplifting books to be printed and to be available. No Tom Jones or Moll Flanders, thank you. A benevolent coal mine owner might establish a library in a colliery town and stock it with books like, How to be a Good Employee, Coal Mining for Beginners, The Joys of Being a Child Miner, Taking Care of Tools, How to Survive on Gruel, Pray don’t Strike, Church not Union, and other such titles. Few locals visited such a library more than once. They wanted light, escapist fiction to divert them for a time from the realities of their lives or literature that promoted a better future in the here and now, not in the afterlife.

This demand led book printers and sellers to form subscription reading libraries to cater for this taste. This struggle went on for a long time, and in the early Twentieth Century Mr Mills and Mr Boon came along and supplied one part of this market, and still do.

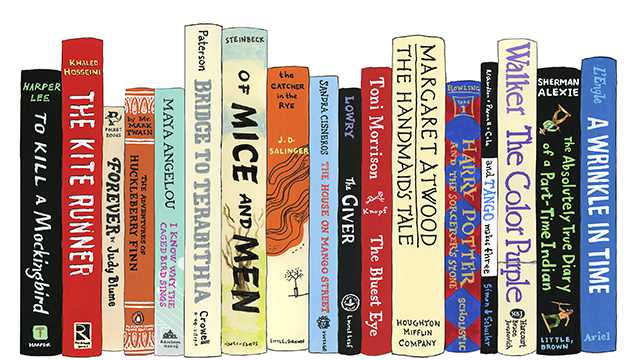

In the Cold War libraries were again in the firing line. Demands were made to purge the shelves, but to warehouse the books to keep them out of circulation not to destroy them. The Bolsheviks of 1917, after the initial thrill of victory, realised they could sell the seized libraries, much of which were in Latin, French, or German, of the aristocrats to the West and did so. But in the USA the goal was to silence the books period, but it was too close to the end of World War II to license Nazi book burning, however tempting that was. Below are some of the books recently banned in Florida.

The story in France is distinctive. After the Revolution of 1789 in the heady days of victory the winners declared all libraries public, the first and biggest of these is the Mazarin Library (which I have used), but they soon realised the stock of books was very Catholic, very aristocratic, and very reactionary. They then banned just about everything and devised a censorship system that was so complex not even René Descartes would have been able to navigate it. When Catholicism made its periodic rebounds, those forces wanted psalters, hymnals, books of days, and little else. When Jean Jaurès’s (1859-1914) socialists rose, they decided to make the local school room with its few dictionaries and primers the public library in the charge of an overworked and underpaid teacher. Thus a public library system was created without the expense of a building, staff, or funds to buy books. It was zero-budget policy hailed as genius.

It was only in the 1970s that the French government funded a huge initiative to create médiathèques, several thousand of them to accompany the Minitel revolution. (Who remembers Minitel?) These were multi-media cultural, community centres and quite by accident have become the model that underlies a great many public libraries today like the one I visited the other day. On now entering a library no longer does one feel like one is entering a memorial tomb where all is hushed, if not quiet. Originally intended as a site for public access to Minitel and its adjuncts, the médiathèques have endured by adapting.

Andrew Carnegie paid for the library building in which I did my early reading; it was one of 5000 he paid for in the USA and UK which then included Ireland. The deal was, he would pay for a building, if the local town council would supply the land and commit to spend a sum equal to 10% of the building cost to stock and staff the library every year thereafter. He offered six or seven types of building that might be selected, and if a town want to embellish or add to one of those at its expense, fine, but all had to include a Children’s Room. I am sure a shade of Herbert Marcuse can explain why this is an example of repression.

Recounted is the hubris of the San Francisco Library that anticipated a future library without books, and so built at great expense a new public library with space for only a third of the existing book stock, and there being no budget leftover for storage, pulped much of the remainder or sold it (perhaps legally). According to these authors no records were kept because the card catalogue was the first thing to go and with it all the meta-data.

There is a lot more in the book, but there is also a lot that isn’t there. It seems to me to be more about book collections than libraries. By that I mean there is nothing but a few asides about how the collections would be organised for retrieval, stored against degradation, restored after damage, the professionalism of librarians, the gender balance among librarians, and so on.

While closed versus open stacks are mentioned, that question is not connected to shelving. For open stacks to work there has to be some order based on content, whereas for closed stacks a shelf mark will do. That is in open stacks all the books by and about Aristotle will be proximate, not so for closed stacks.

Nor do they mention that marvellous short story by Juan Luis Borges, The Library of Babel with its Purifiers patrolling the shelves on search and destroy missions like those now occurring in Florida. Nor does this book mention Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 and the ineradicable quality of the ideas in books. Nor the German librarians who secreted books from Nazis.