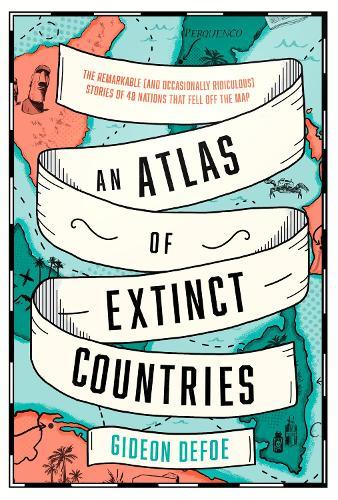

An Atlas of Extinct Countries (2020) by Gideon Defoe

Subtitle: The Remarkable [and Occasionally Ridiculous] Stories of 48 Nations that Fell off the Map.

Genre: Non-fiction, though some of the countries were all but fictitious.

Verdict: no more!

Tagline: No kidding? No kidding!

The motley crew is divided into four parts, each is twofold:

- Chancers and Crackpots who declared themselves king of an acre, like Prince Leonard in West Australia though he doesn’t make the cut here. Most of the examples treated occurred in the age of colonialism when a European would chance upon a clearing in a forest or an island in a stream and crown himself. Yes, though the author does not underline it, they are all men. He includes here the Kingdom of Bavaria, which despite the insanity in the royal family, was a country from 1805 to 1918. Ditto the kingdom of Sarawak (1841-1946) without the insanity.

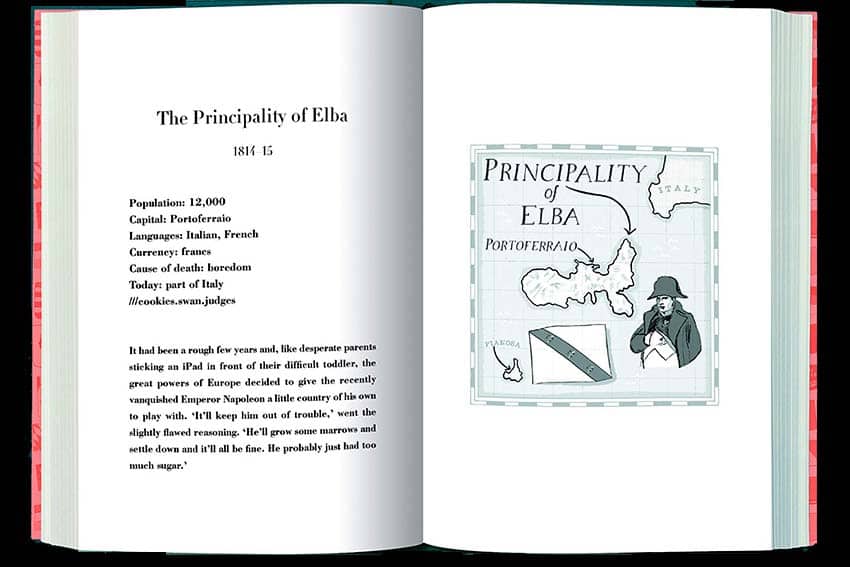

- Mistakes and Micro-nations. This section includes the ludicrous story of the Scots attempt at colonisation in a Panamanian jungle that is still uninhabitable; they bought the land cheap, being Scots. The most interesting other specimens are Elba when Napoleon briefly ruled it, 1814-1815 and Tangiers when it was an international city from 1924-1956. The later served as a backdrop to much thriller and spy fiction long after its 1965 absorption into Morocco. Don’t forget the tangerines, either. (Though it is curious that it went quietly into Morocco but the three Spanish enclaves along the Moroccan coast did not, and still have not, being the last examples of European colonialism.)

- Lies and Lost Kingdoms. There were scams before the internet! An entrepreneurial soul would dream up a luxurious and wealthy unclaimed land where gold grows on trees, and sell shares in it to investors and settlers, then – in the time honoured fashion of bankers – take the money and run. Credulity is as old as the credulous. Old. Lost kingdoms include Sikkim (1642-1975) and Dahomey (1600-1904). Nobody wanted Sikkim, not even India, but as a buffer against China, it relented. Dahomey became a French colony of the same name, known to stamp collectors, until de-colonisation created Benin (now famous for its bronze artwork to viewers of The Antiques Road Show on BBC). The author includes here The Serene Republic of Venice (697-1797) when Napoleon ended it in person by burning the Golden Book and supervised a shotgun wedding with Italy. Methinks Defoe whitewashes Venice’s tortured and violent history, omitting the piles and piles of dirty laundry.

- Puppets and Political Footballs. There are both important and unimportant examples included here. As the latter, various proto-states in North America, like West Florida (which lasted a few days and was located in Louisiana); as to the former the Texas Republic (1836-1846). Three others were even more significant: Yugoslavia that preserved ethnic hatred in amber for forty years, The Deutsche Demokratische Republik (1949-1990) that de-populated itself by a quarter while bankrupting itself, and Mussolini’s last respite, the Salo Republic (1943-1945), that gave the Germans free rein to what was left of Italy and its Jews. Here the author includes the terrible story of the rapacious and inhuman plunder of the Congo. Manchukuo (1932-1945) is in this section, a puppet state set up by the Japanese to cloak their brutal colonisation of this iron ore rich region.

There follows an appendix with some comments on the flags and anthems these places had, ranging from the silly to the stupid.

Omitted are the Second Spanish Republic (1934-1939) which had its own flag and anthem, as did Australia’s very own aforementioned Prince Leonard (1925-2019) of the Principality of Hutt River. Maybe the Spanish Republic isn’t qualified since it did not change the borders nor the existence of Spain. But as to crackpots, well, Lennie is hard to beat. Check him out on Wikipedia. Then there is California that declared itself a republic for thirty days, and the kingdom of Hawaii. Wasn’t Vermont also briefly an autonomous unit?

Each entry is written to a template of about five pages with a small map. The result is superficial but the treatment is spritely, and when you know nothing, an informative start. There is a short, but well-judged bibliography to continue with.