Balzac as He Should be Read (1946) by William H. Royce

Good Reads meta-data: it is listed without any details. It has 48 pages.

Tagline: Useful.

Verdict: A gem.

A retirement project I once had in mind was to read in sequence Honoré de Balzac’s La Comedie humaine. I made a false start more than a decade ago and got bogged down in one of his novels that was epistolary, letters between two sisters, which was boring. He must have needed the francs per word and spun it out. The reading I did then was in publication order, which is not the sequence in which his grand comedy of life fits together.

The difficulty at that time was compounded because the Rocket e-Book reader of the day did not make it easy. The text was there but not word wrapped on the screen. That made a considerable difference to my surprise. Moreover the only available digital editions were out of copyright Victorian translations that were censored and stilted

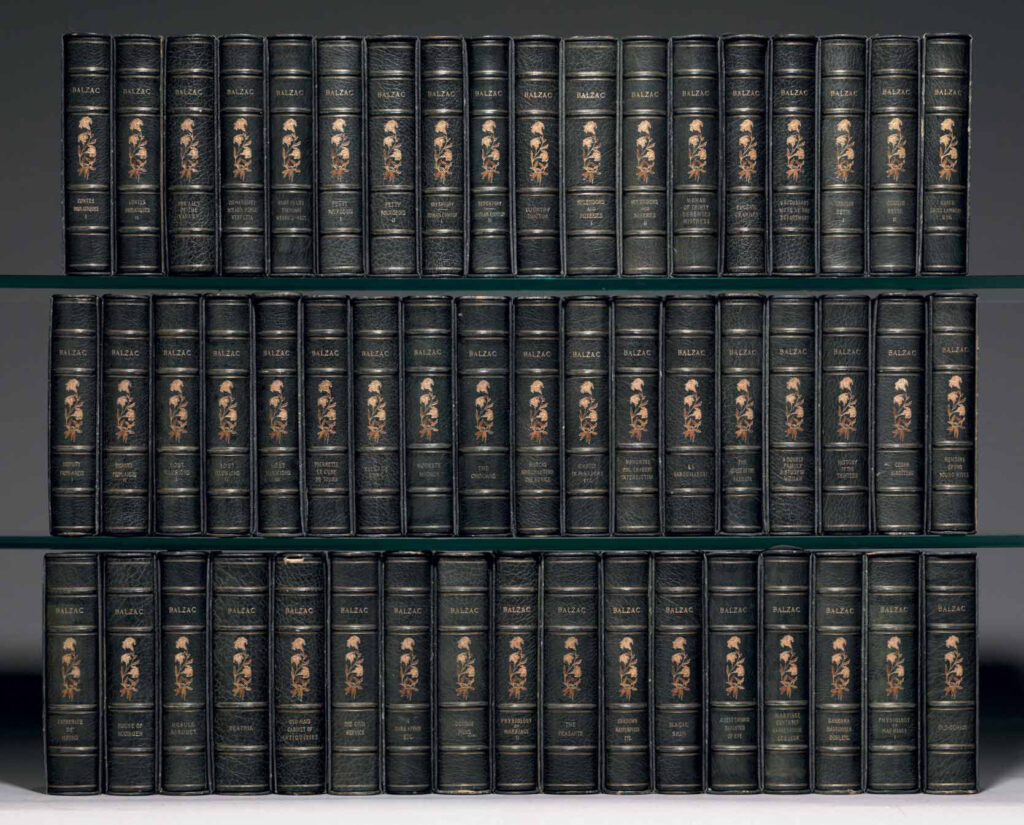

To begin anew, I needed a kick start, and this little book did it. In case a reader does not realise why a spark-plug is needed, please note that more than ninety (90) stories comprise the whole, and many of those are full-length novels. Balzac was a Niagara of words.

Royce offers three suggestions about how to immerse oneself in Balzac’s waters. One is to read in publication order as I tried. Royce himself rejects this because in subsequent editions, Balzac manipulated the sequences to suit the growth and interaction of the 2,450 characters he created on the page. The time of publication did not coincide with the overall narrative which grew in all directions, including backward. Ergo to read a novel published in 1840 set in 1840 before one published in 1842 with many of the same characters set in 1830 when they were younger convolutes the narrative in favour of the publication date. Balzac often birthed characters at age 30 or 40, and then later went to back to them when they were younger. Eugène de Rastignac appears in nearly thirty of his novels at different ages. Needless to say these thirty were not published in chronological order of Rastignac’s age. (See Anthony Pugh, Balzac’s Recurring Characters [1974] for pedantic detail.)

Second is by the order of events dated in the novels and stories and this he offers to the reader with the gargantuan appetite for the whole. Let it be noted that Balzac is largely consistent on dates within each novel and refers to an event or person that can be dated in nearly every story.

Third, embedded in that chronological list Royce bolds the titles of twenty novels that he deems the core of the Comedie humaine. That is a much more digestible banquet, and since long ago I read The Chouans, Père Goriot, the Wild Ass Skin, The Unknown Masterpiece, and Cousin Bette which were included in that twenty, I had a running start with this selection. Assuming those six I went to Amazon to find a Kindle version of the next novel: Une Ténébreuse Affaire. It has many titles in English but none are available for Kindle.

While confirming that absence, Amazon began besieging me with other titles, and I bit on one which I will comment on later. Suffice to say here that it is a biography (not of Balzac) but of seven of his principle characters. It was an intriguing idea and I have started on it to my satisfaction. More on this later, if you are good.

Personal indulgence. The first Balzac title I read was Père Goriot in high school for an AP World Literature class. The other Balzac’s I read in college for a similar class. What do students read today in high school classes? Comments welcome.

I went through Maison de Balzac in 1980, but all I can remember is that there was a secret backdoor through the rear garden that he used to escape the creditors and bailiffs when they came in the front door, usually by kicking it in. He moved around a lot and used false names to elude debt collectors who were legion.

Royce’s long out print book came into my hand thanks to Katester’s perspicacious insight in making it a Christmas gift.