Felicity Wood, Universities and the Occult Rituals of the Corporate World (2018).

Good Reads meta-data is 219 pages, rated by …. [It is listed without any readers’ reactions].

Genre: Polemic.

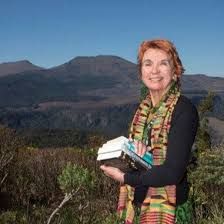

DNA: South Africa.

Tagline: ‘Dr Faustus will see you now.’

Verdict: Depressing.

Felicity Wood has long studied occult witchcraft and its allied practices in sub-Saharan Africa, and as she observed the evolution of the corporate university in the last decades she became aware of the similarities between the managerial practices that grew up in them and the rituals of myth and magic in the occult.

Amen, sister.

Superstition takes many forms, besides religion. The book offers to an increasingly depressed reader a detailed comparison of the metaphorical similarities of these two worlds.

She makes that case in good part by quoting from the maelstrom of mission statements, performance goals, impact declarations, management directives, justifications for near perpetual re-organisation, and so on issued by the managers of universities far and wide, not just South Africa. While a reader may not accept entirely her premise, still one nods in agreement very often with her comparisons and interpretations.

Just as witchdoctors never proffer evidence for the effectiveness of their ceremonies but instead offer explanations of why more witch-doctoring is always needed, so too managers. When managers managing does not spin gold that can only be because even more managers managing is required. And more.

If the words of university managers are taken as invocations of spirits, well, that makes as much sense as trying to take them literally since most of the rhetoric is hollow: excellence, quality, impact, and so on are intoned at every breath, yet no one knows what they mean. But like prayers, perhaps mouthing them pleases the unseen powers of market, economy, and the most high and mystical of all – money. Mammon is indeed our god, and few of us prove worthy of that deity.

A few quotations follow to sample the text.

#####

‘One respondent contended that one specific vampire tale was factual, saying, “It was a true story because it was known by many people and many people talked about it.” (Luise White, Speaking with Vampires: Rumor and History in Colonial Africa (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000), p 31.) All too often, the corporate fabulation at restructured universities has been made to seem more convincing by this means. A mantra has been repeated so many times that it has become reality.’

‘Wholly fictive place called “the real world” is quite unlike the actual world you and I live in. .. . [T]his invented entity called “the real world” is inhabited exclusively by hard-faced robots who devote themselves single-mindedly to the task of making money.’ Rational calculators of material self-interest and nothing else.’ It is as false as reality television programming.

‘They also owe their prevalence to the fact that they have been utilised to reinforce a further, related piece of corporate folklore: the notion that private profit is synonymous with public good.’

‘In general, the fantasy seems to prevail that by imitating corporate models, imposing managerial chains of command and invoking the jargon of the corporate world, as well as some of the mythologies that emanate from it and reinforce its ethos, a magical transformation can be wrought, by means of which universities can be transmuted into more productive, accountable and efficient institutions, working for the greater public good. This state of affairs has come to pass as a result of a faith in the near-magical potency of the corporate world, fuelled by the vague belief that the corporate sector, situated as it is in local and global marketplaces, is closest to the sources of economic profit.’

‘This might be one reason emphasis has been on outward forms and ritual activity, rather than meaningful substance. Indeed, market-oriented institutions tend to be characterised by their ritualistic imitations of the corporate sector and their symbolic enactments of certain key qualities associated with this domain, such as excellence, quality, productivity and accountability.’

‘The voodoo-like potency of words include quality, excellence, mission, premier, benchmark, strategic, top rank, world-class, flagship, team-building, auditing, performance, accountability, and even ethics.’

‘Quality is a term laden with mystery and magic partly to compensate for the fact that, like excellence, it is essentially a vacuous term: a receptacle into which different meanings can be poured. As one of the principal words of power, the word quality is routinely uttered for purposes of ritual and enchantment, as if calling on this concept will cause it to manifest itself.’

‘Like quality the word mission has spiritual resonance evoking the image of a sacred quest.’

####

It is great fun to read, though hard-going, because even as the text ridicules the prolix jargon of corporatism, the book itself is riddled with an an opaque vocabulary of –isms , –itions, and –ites drawn from social science. Much of this vocabulary is as vacuous as that which it bewails. Sad, but true.

I had hoped for some reality testing for the mystical properties of business that make it efficient and effective. My experience of private business — large and small — has sometimes shown it to be incompetent, indifferent, confused, inconsistent, idiotic and the like. And yet successful. The volatility of businesses that come and go is likely to be due to these factors rather than to vigorous Darwinian competition. This is true in both large and small examples.

Check you Enron or Boeing share prices for evidence, or book a musical chairs seat on Qantas.

Good old days as she frequently notes were different but not better, but I have omitted those remarks since I know them so well.

Not a book likely to be reviewed in the higher education press and literature.