———

Operation Mincemeat (2010) by Ben Macintyre

Good Reads meta-data is 416 pages, rated by 4.02 by 20,290 litizens.

Genre: History.

DNA: Brit.

Verdict: Overloaded.

Tagline: Tis a far better thing than he had ever done before.

Espionage has many forms and disinformation is one of the principal ones. To mask the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943 a deception plan was conceived, prepared, and launched to confuse the Nazis. It would be impossible to conceal the fact that Sicily was the next geographically logical target, so the plan was to capitalise on that obvious fact by implying that a feint would be made to Sicily while the real attack would be on the Peloponnese in Greece with the strategic goal of a link with the Soviets via Yugoslavia.

Winston Churchill had often spoken of the soft underbelly of Europe, evidently having never seen the mountains of Italy or the Balkans, and the site would be consistent with that. But how to do it?

What would convince the Nazis? Soft intelligence of rumours and such is useful but that takes a lot of time and there was little time for that on this occasion because it was in February when the decision was made to invade in July. Still rumours were planted, but something that would rivet attention would be better. It had to be something that the Nazis found out for themselves and interpreted for it to have credibility with them. It could not simply be handed to them. So a complicated and roundabout plan was hatched.

An airplane crash would be faked off the coast of Spain at a place where the local officials were known to be pro-Nazi. A cadaver would float ashore with a brief case chained to a wrist containing some papers which were vague, but which lent themselves to the interpretation that the next major objective was Greece.

That sounds pretty simple but the preparation and execution was anything but simple. The imperative of secrecy meant everything had to be done carefully. (Although by launch date at least 50 people or more, by my count, knew the broad outline and purpose of the exercise. The author does not offer this kind of numerical summation.)

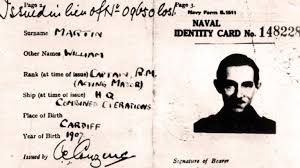

Every step was hard. In wartime England finding a dead body to use was the first, and in some ways the hardest problem. One of the good points of this book is the deference and respect accorded to the deceased, one Michael Glyndwr. Eventually, against an ever ticking clock, a cadaver was found that (1) could be used (no family to claim it, no witnesses to its death, no obvious signs of the real cause of death), (2) of military age, and (3) roughly physically fit enough to have been in the army: Someone who is not going to be missed or sought after. The final difficulty was the identity photograph on his service card. The dead do look dead.

Once found, a body would have to be kept for some weeks while the papers and other paraphernalia were assembled and the seasonal tides became right off the Spanish coast. There was no point in preparing the papers and gear if no corpse could be obtained so that only started once the corpse had been secured.

Getting a uniform also proved difficult, since every item of clothing issued had to be accounted for and assigned to a soldier. Most difficult of all, because they were the scarcest of all in wartime England, were underwear!

Preparing the papers also proved a challenge. No one was satisfied with the drafts others wrote, and so more drafts were written, each typed with copies by office staff. Imagine a committee of twelve writing a letter! Impossible.

Even harder was faking a plane crash. Even getting an RAF plane to fly the body to the right locale proved difficult. One could hardly say we need it for a secret mission to deceive the enemy to the RAF to file flight plan. Instead a submarine did it in such a way that only two intelligence officers saw the body. The crew of 60 certainly knew something unusual was happening. Using the submarine allowed for a more exact placement in the tidal action. (The crash was faked with an explosion on the water.)

While all this was going on, the cadaver was decomposing in cold storage.

Apart from these practical hurdles, the toughest nut to crack was pitching the information so that it tapped into the predispositions of the German intelligence analysts. Not too much, just enough for them to find confirmation for what they already suspected.

Another key, apart from Churchill’s focus on Southern Europe, was the British presence in the Balkans, mainly with Tito’s partisans, but also a remnant of British troops that had gone to ground in Greece when they could not be evacuated in 1941. These were stirred into some action to support the story. Meanwhile, in Egypt Greek-speakers were recruited and organised.

He had to be named, and every serving officer was in the Army or Navy Register. What name to use? This was a comedy of errors. The name of dead officer could not be used for reasons both practical and moral. And so on, and on. But it had to be a name in a register but who would not be surprised to hear he had died, because his death would be published. Long story on that one. Because once the body was found in due course it would be identified and buried.

Once the man was in the water, there was a wait to see if the tides had been correctly predicted. Yes.

When the body was recovered would it pass examination by a coroner? Yes, but only just. In fact, the Spanish medical examiner entered all manner of hedges and qualifications in the written report about the cause of death, how long the body had been in the water, and time of death but this report, by luck, did not accompany either the cadaver or the briefcase thereafter.

Then would the Spanish hand over the papers to the Germans in Madrid. No! Some fool in the Spanish bureaucracy followed correct procedures and locked the papers up, pending release to the British after the body was identified, claimed, and buried by the Brits.

A contingency plan went into operation to alert the resident Germans in Madrid (there a lot of them — about two hundred — who preferred that posting to the Eastern Front) that the papers existed and were valuable. This was done by starting word-of-mouth rumours of a British reward for the return of the brief case and contents. Not a colossal amount of money but enough to set the German mind thinking.

There was a lot of cat-and-mouse in Spain. Once the papers were finally in German hands, the Nazis saw what they wanted to see. In Spain the resident Germans needed an intelligence coup to make themselves look good to their bosses back home in Berlin so they could stay in Spain. Their willingness to believe was duly noted in London and exploited with the later Normandy deception to come.

In Berlin the OKW army analysts wanted something definite to concentrate on, and this gave them a target. Despite all the stereotypes of German realpolitik and efficiency what shows here again is the incompetence, disorganisation, and fantasy in much of their intelligence work. Just as bad as S.O.E.

And of course once Hitler accepted the truth of the Greek misdirection, no one else dared criticise, equivocate, question, or hesitate. When the information proved wrong, of course, Hitler blamed everyone else but himself. This same cycle of incompetence and stupidity was repeated with the deceptions regarding the Normandy invasion a year later. Once again Hitler was fooled, and that was that.

In neither case could or would Hitler ever take responsibility for his own mistakes. Now that is genius!

There was another wait once the papers reached Berlin to see if they were examined, and acted on. Well, after a wait, Field Marshall Erwin Rommel was sent to Greece. He took with him two fully equipped armoured divisions that were then not in Sicily when the Allied landings occurred.

The author has amassed a great deal of material, all of which is presented! There are too many back and side stories about the alcoholic intake of the Brits during the war. That may well explain S.O.E.’s catastrophic incompetence. Not so very amusing viewed in that light.

A strong point is the account of the forensic assessment of the papers and the cadaver. By the same token I would have liked a little more on the attitudes of the Spanish officials involved.

I read The Man Who Never Was (1953) by Ewen Montagu (the main architect of the plan) (168 pages, rated 3.96 by 1412 litizens) when a lad of an (un)certain age. When the film of 2021 came around I was reminded of that. However, I did not go to the movie at the local Dendy since having my ear drums assaulted for 2 hr 8 min after having my patience exhausted by the repetition of Val Morgan ads repeated three times, after having paid the $24 price of admission did not appeal to me. Curmudgeon that I am. Perhaps one day I will see it on the telly chopped up by imbecilic commercials, but that is what the mute button is for.