Deborah Logan, The Hour and the Woman: Harriet Martineau’s “Somewhat Remarkable” Life (2002)

Good Reads Meta-data is 332 pages rated 0 by 0 litizens.

Genre: Biography

DNA: PhD

Verdict: Indeed, remarkable.

Tagline: Too much is not enough.

First to the woman, then to the hour. Martineau (1802-1876) was an influential writer in the Victorian Era. In that age of reform, she was a REFORMER with the pen. The causes she took up often fell hardest on women, but not all of them. She was a social analyst, social critic, and social advocate of a high order. Later in life her admiring readers included Florence Nightingale, Queen Victoria, John Stuart Mill, and others of their like.

Her Unitarian father owned a factory in Norwich and he encouraged his daughters as well as his sons to get educated. When his factory later fell on hard times, to make money Martineau made and sold needlework, something she continued to do throughout life, donating the proceeds when she could to the causes, and also took up the pen. Her first foray was Illustrations in Political Economy, where she illustrated economic concepts with stories, combing fiction and non-fiction. Efforts to secure publication of the first of these by correspondence failed, and she did not even think of using a masculine pseudonym, but rather she did what a man would do. She went to London to argue her case with publishers face to face. It was difficult but it worked. She found a publisher desperate enough to take a punt on an unknown writer, an unconventional mixed genre, a provincial, and a woman on a new subject.

The first exemplar was published, and….it sold every well. It was reprinted and distributed further. That led to eleven more. The result was more cash money than the family had ever seen, and set her on the a road she never left. It also gave her a notoriety that was mixed, for publishing was men’s business, and the reviewers let fly with a barrage of ad hominem (or is that ad feminem) attacks that would please an internet troll today. These continued the rest of her life: personal, malicious, threatening, incoherent, ranting, and stupid fulminations.

She continued apace with other social questions, and when money and time allowed she travelled to the United States in the same year that Tocqueville did, 1835. While he carried letters of introduction from the French government, he went as an ingenue looking for a key to the kingdom of democracy, she went as a social critic to observe the life of both women in this New Jerusalem and of slaves. She found that women’s world was no different in the US than in the UK. She also added abolitionist stripes to her colours. (In the effort to emphasise Martineau, our author rather undersells Tocqueville. See his prophetic chapter The Three Races.)

While she promoted female emancipation, she did not advocate the franchise for women. She thought that education and autonomy came first, then the vote. If the vote came prior to social, intellectual, and moral emancipation, it would be manipulated by men who dominated women. The arguments are clear and logical, but, well, impractical. It is a variation on that recurrent nostrum: first utopia, then national health.

She spend years battling the Contagious Disease Act which permitted the seizure of women on the grounds of public health (venereal disease) and imprisoning them. That the government owned the bodies of women whereas it would never even consider a like possession of men, drove her pen into open warfare. Not only was the Act wrong in itself, it was misused and abused to subjugate women. The cannibals had at her but she did not flinch. Yes, there are contemporary resonances here, too. (Strangely neither Martineau nor our author consider military conscription as a relevant comparison to this point.)

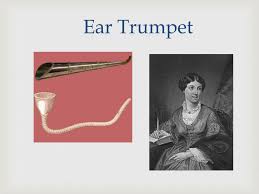

If all this were not remarkable enough, she did it while enduring a debilitating handicap. She became deaf at an early age, and thereafter brandished an ear trumpet, and later a walking stick, and suffered extended periods confined to a bed. Yet she soldiered on. (I wondered if this loss of hearing was related to her penchant for writing to communicate? And how that related to learning French? But no answers did I find.)

This is a book about her life but it is not a chronological biography and rather assumes the reader knows the facts of her life – which I found on Wikipedia. What it offers is a thoroughgoing analysis, interpretation, and evaluation of Martineau’s intellectual achievements and heritage piled high and deep enough for a PhD. That means it is hard sledding to a casual reader like this correspondent. I chose it because I knew her name as a forerunner of Sociology, and while that is here, it is not emphasised. Did she compile data and present it, as Florence Nightingale did, or not remains unknown to this reader. Or did she rely on polemic? She translated some of Auguste Comte’s doorstop books but how and why she learned enough French to do this, and whether it was cause or effect of her social interests remains befogged to me.

The book is divided into 50-page chapters that wearied me, weak reed that I am, and the level of argument at times is as mystical as a priest reading entrails. Finally, nothing is good enough for Martineau. Previous writers who have praised her are arraigned for failing to praise her in the right way, for failing to praise her enough, for failing to praise her on time, and so on. The compound of these features and their kin is overkill.

She would certainly was a good subject for a ‘Great Lives’ program on BBC4 rather that some of the stand-up comedians that are so common on that once very informative program. That is where I was reminded of her, and that led me to getting this book.

——-