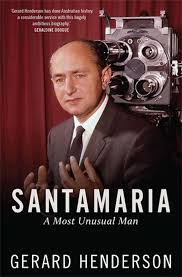

Good Reads meta-data is 512 pages, rated 3.80 by 10 litizens.

Genre: Biography; Species: Hagiography.

DNA: Strine.

Verdict: Time conquers all, Bob.

Tagline: A philosopher-king without a throne.

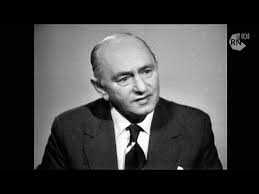

Bartholomew (Bob) Santamaria (1915-1998) was a major figure in Australian public life for two generations, yet he never held a public office, though many of those who did so looked to him for guidance, including a recent Prime Minister (who liked to pick fights with people who never heard of him, that being so much easier than governing for all the people).

Much is made of Santamaria’s service in World War II. It is resolved by Santamaria’s own testimony. Be that as it may, I wondered why there were no archival records that applied to this question of fact. But on this point, and many others in the book, saying it was so makes it so.

Santamaria had a weekly column in the Australian newspaper from 1976 and a 7-minute Sunday television program called Point of View sponsored by the National Civic Council which ran from 1963-1991. There are episodes on You Tube. (His column and television comments were in English. I mention this because comparable Catholic television in Quebec of the early 1970s was in Church Latin, if you can believe it. Believe it, because it is true.)

Earlier he had founded and run The Catholic Worker to counter the Communist Daily Worker. In its pages he found a red under many a bed. Soon he was a force in Catholic Action in Australia (see Tom Truman, Catholic Action [1960]), a Catholic soldier marching and marching his whole life, continuing to do so long after that war was over.

His most famous role was in ‘The Split’ that divided the Australian Labor Party and condemned it to the electoral wilderness for a long generation. This is a complicated story but the kernel is the influence of communists in trade unions which in turn influenced the Labor Party. The omens were there for those with eyes to see: A loud and proud Labor minister in previous governments revelled in the nickname Red Eddie. A noted Canberra historian of the time was awarded an Order of Lenin. It was a time of mass immigration from both post war Europe and Asia, and many, like Santamaria, supposed communist sympathisers and infiltrators were among them. Then came the Petrov Affair to confirm the menace.

Unlike many rabid anti-Communists of the 1950s, Santamaria was calm, measured, insightful, and stuck to facts most of the time. That gave him creditability beyond the hard core. The result was the Democratic Labor Party which supported the Liberal Party by siphoning votes from the Labor Party. See, I said, complicated. (For those that don’t know it, The Liberal Party has never been liberal.) In all these ways and means he had more influence than most knights of Rome.

He continued to fight this fight long after it was lost and that combined with his adherence to a medieval version of Catholicism meant that the march of time left him behind by the 1960s. One can only speculate on his reaction to the Beatles tour of Australia, including Melbourne, in 1964 (because it is not mentioned in this text), but it’s fun to do so. Labor Party leaders began to use his intransigence to illustrate the dead hand of the past. Dogmatic as he was, he maintained good personal relations with many whom he opposed in the Labor Party. There was never then nor now any reason to doubt his sincerity, unlike the many opportunists who rode the anti-communism bus to fame and fortune.

His final rearguard battles were against snail’s-pace changes in the Catholic Church itself, especially regarding contraception. He was, as the saying goes, more Catholic than the Pope. He also wanted to turn the clock back on professional sports, homosexuality, the ABC, and much else, stopping the march of time around 1936.

I said ‘hagiography’ above but it is true that Henderson notes Santamaria’s blind spots, inconsistencies, ego, and the like, but still the tone is reverential. Henderson is less sparing with rival acolytes like Robert Mann, and that was very enjoyable.

The book offers a wealth of detail, names, dates, meetings, reports, speeches, piled into a ziggurat, but the altitude yields no insight, and after my reading I did not feel I knew Santamaria any better than when I started. The man himself is obscured, not revealed, by the blizzard of details that comprise the book.

What I can say is that Santamaria was parochial Melbourne through and through, with little reference to the wider world beyond the Yarra River. He seldom traveled and when he did, well, he went to teach not to learn; to give his wisdom not receive any; and to tell not to see or listen.

Nor is there any evidence in these pages that he mixed with the racial, cultural, social, generational, aspirational, diversity that Melbourne was becoming in the 1960s and after. His reaction to the Labor election in 1972 was fatalistic. How could people be so wrong? Back to bully pulpit he went with renewed energy.

Upon reflection, the details are so many that it almost seems the author himself is trying himself to find the man in the jigsaw puzzle pieces of the information he has amassed. By the way this is Henderson’s second book on Santamaria.

Questions remain for me. Why did he (and his parents) prefer ‘Bob’ to ‘Bart’? Was he tempted by the priesthood because that was certainly his calling? Henderson touches on these points, but that is all it is, a touch: Enough to underline the question not enough to shed light.

***

By the way, I borrowed an electronic copy from the library and read it on the Kindle as a PDF.